The seventh and concluding post in a series of dispatches from freelance writer Brandon Reynolds aboard the USCG icebreaker Polar Star, on its annual resupply mission to the research base, McMurdo Station. It’s a critical task imperiled by the nation’s aging, shrinking fleet of ice-breaking ships.

Everyone must inevitably deal, at some point, with “the break-up.” It wears different disguises in different places — the surprise invitation, the unexpected pregnancy, the phone call late in the night — but you know it simply as that which changes your direction.

In McMurdo Sound the break-up is what happens to the fast ice that stretches from volcanic Mt. Erebus on the east all the way west to the edge of the continent. Just about every year the ice around McMurdo breaks up late in the season. Wind force, melting caused by seawater and the actions of a certain plucky icebreaker destabilize the whole giant ice sheet where once we ran around with penguins.

Thursday afternoon the captain mentioned that a crack had formed across the whole channel. By midnight a 147-square-mile section of the fast ice had broken off and begun floating away north. In a few hours, weeks of work spent grooming the channel all just blew away. Once, there was a path through ice. Now there’s open water. Imagine building a bridge every year, and every year it gets washed away.

We spent three days at McMurdo Station, which is a little like a mining town, or a moon colony. It feels very far from the rest of the world. The people are an interesting bunch, scientists and contractors, exactly the kind of people who wish to live very far from the rest of the world. There is pizza 24/7. Just down the road is New Zealand’s Scott Base, which is smaller and uniformly painted a delightful shade of pea green.

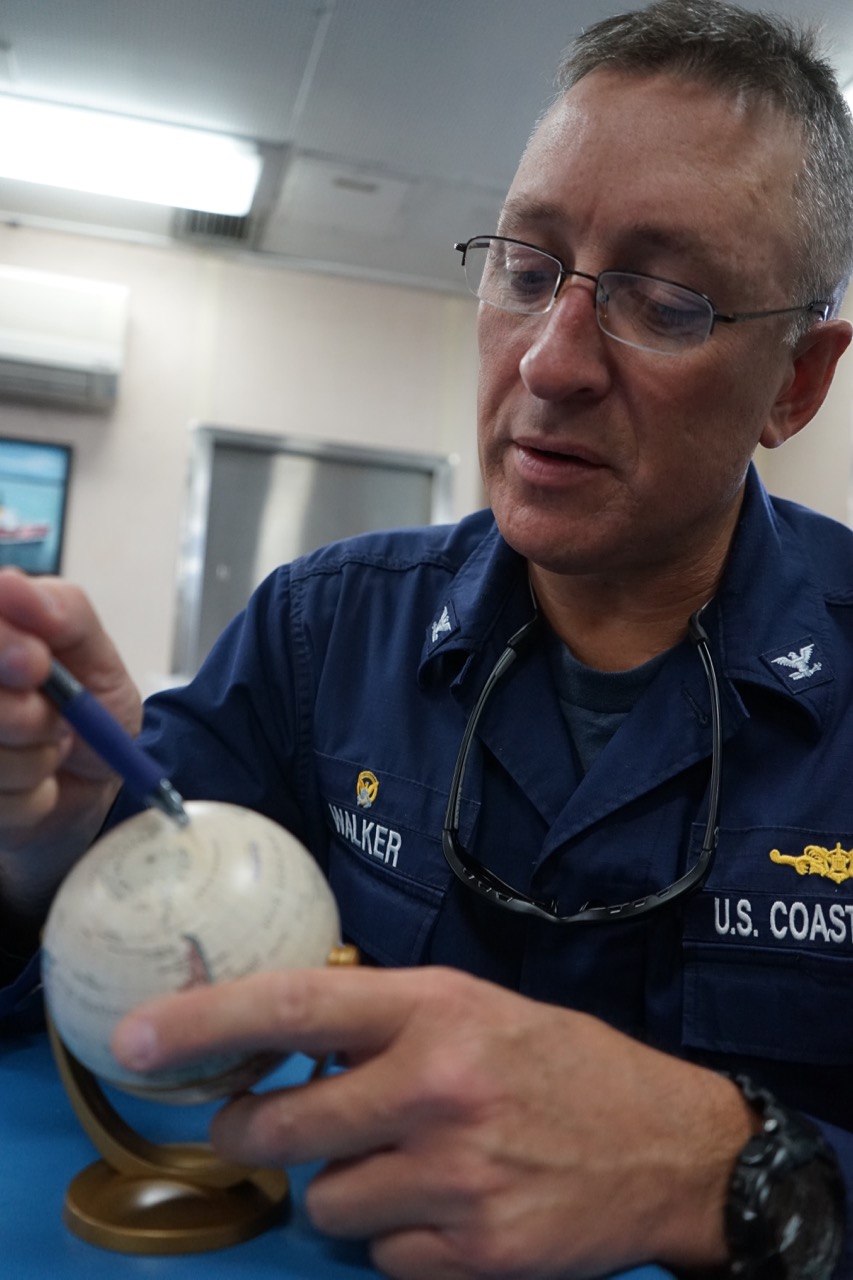

We’re now in the midst of McMurdo’s annual resupply. The freighter Ocean Giant is docked, offloading a year’s worth of supplies and collecting a year’s worth of trash and freeze-dried poop, or so I hear. We’ll escort the Giant out, meet up with the fuel ship, bring it in. Once it’s offloaded its fuel, McMurdo will be supplied for the next year. Through McMurdo, the rest of the continent will be, too, because, as Capt. Matt Walker points out, “McMurdo is the major port in Antarctica, so all of Antarctica feeds off of McMurdo for its supplies and logistics.” It’s no exaggeration to say that the survival of the continent, meaning other U.S. bases but also many of the bases belonging to other nations, relies on McMurdo. It’s run by the National Science Foundation, which means, in a way, that NSF runs the continent. And NSF relies on Polar Star carving its thin lifeline in the ice, which nature, presently, will erase.

Soon we’ll get the hell out of here and the people at McMurdo will get the hell out of here, too, piling into ski-equipped C-130 turboprops and flying to Christchurch and points north. Then winter arrives to turn endless day into endless night, to blot out the sky with 200 mile-per-hour winds, and to replace the sheet of ice in McMurdo Sound as though none of us were ever here. Whatever memory this place has is carried deeper than the few meters of frozen water the ship plows through every year. We will be remembered by no one save a few photobombed penguins and the odd startled seal. Leave no trace, they say.

Back in the world, with a nudge from President Obama, the Coast Guard this month put out the call for two new icebreakers, saying it plans to award a contract in late 2018 or ’19.