Listen to the Story:

Bay Area Landslide Risk Goes Up as Rains Pour Down

Bay Area Landslide Risk Goes Up as Rains Pour Down

The winter rains have brought sweet relief to California after four years of punishing drought. But as one El Nino-fueled storm follows another, the heavy precipitation can cause its own set of hazards. That includes the potential for landslides.

“How bad this year will be for landslides all depends upon how intense the rains will be,” says Brian Collins, a researcher at the U. S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park. “The water has been pretty constant so there is a danger.”

During most years, many small landslides affect the Bay Area. Catastrophic slides, causing loss of property and life, aren’t common, but they do happen.

The Night the Mountain Fell at Love Creek

In early January of 1982, a heavy storm slammed into the Santa Cruz mountains. Though it was not an El Niño year, the storm dropped 20 inches of rain in just 32 hours—nearly half the area’s annual rainfall.

At the time, Stephen Sanders was a fire captain for the Ben Lomond Volunteer Fire Department. On January 5, the morning after the storm, Sanders was at the fire station when an elderly couple walked in. They’d had to pick their way through debris to get there and were worried about their neighbors living further up the mountain along Love Creek.

“So the Chief sent myself and my brother and another gentlemen up here, ‘Hey, go up there, find out what’s going on.’”

Recently, Sanders and I revisited the gully where, shortly after midnight on Jan. 5, a huge swath of hillside, about a quarter of a mile across, had broken away. A punishing river of mud, rocks and debris smothered the trees, houses and land below.

“We got here about 8 o’clock in the morning, after the sun came out, just like this,” Sanders recalls, standing at the site. “And it was just all—just boulders and clay, mud, and you’re sliding all over. It was terrible.”

Hundreds of people volunteered to search the rubble by hand for bodies. The National Guard came out to help. In the end, 10 people died. Longtime Ben Lomond residents don’t talk about it much.

“It’s very tough for us. These were our friends and neighbors,” Sanders says. “I knew everybody up here. We all did.”

The county designated it a hazardous area, and other homes there were torn down. There’s not much left but rubble and twisted metal.

Landslides Are Hard to Predict

Unlike other catastrophes–like floods or fires–people hardly ever evacuate for landslides. That’s because they are very difficult to predict. Scientists don’t have the tools to know where they’ll strike.

A lot of factors contribute to the potential for a landslide, things like the steepness of the slope, the construction of the soil, how wet it is, and how loose or tightly packed. These conditions change dramatically from one location to another and from one day to another.

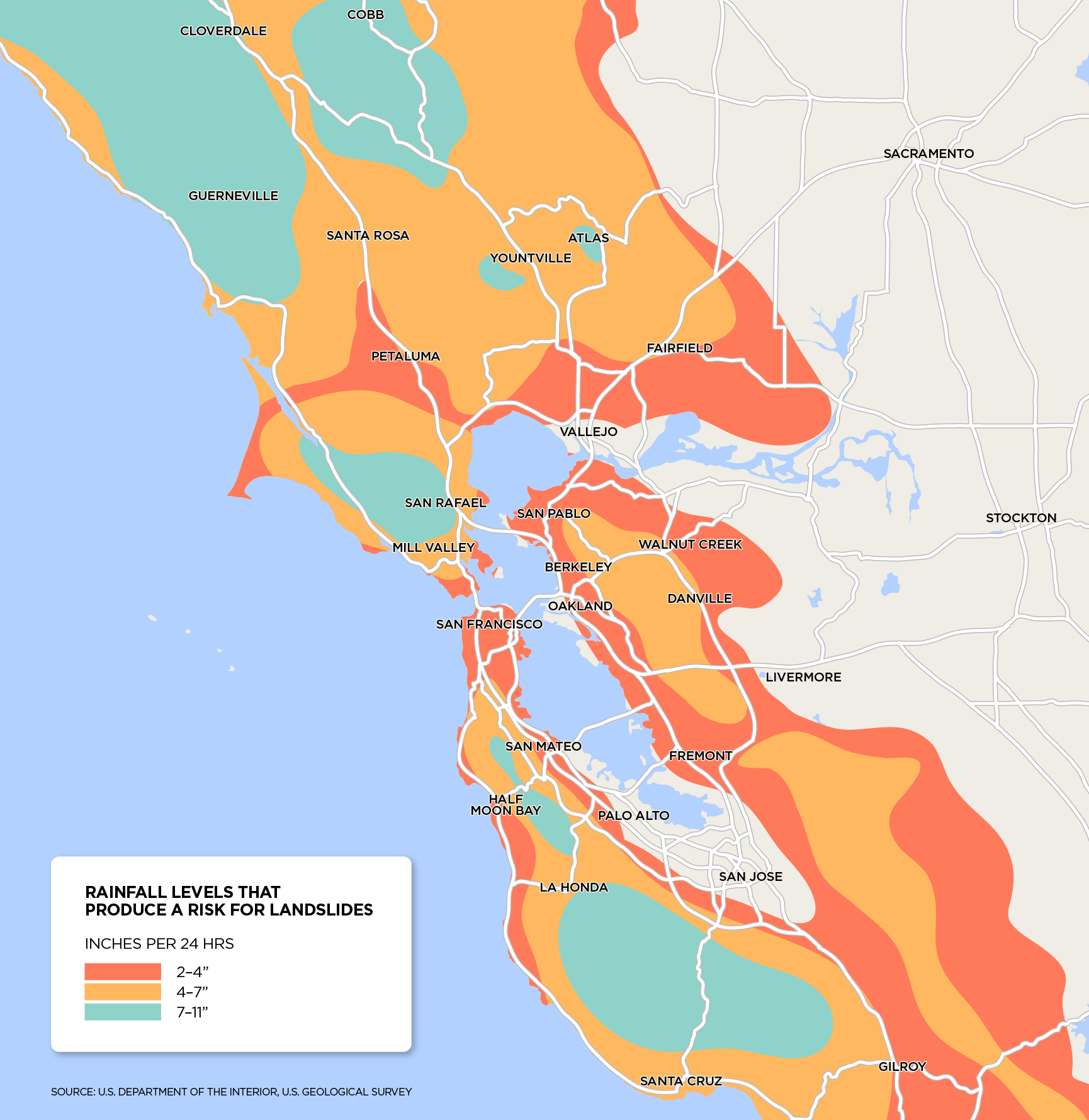

But there is one thing scientists know for certain raises the risk a landslide will happen: intense rainfall on saturated ground.

“That’s why we’re measuring the soil moisture,” says Collins of the USGS.

The agency monitors soil moisture in the Bay Area to get a sense of how saturated the region is, but it’s a new area of research and they only have sensors at four sites. If the project goes well, more could be installed in the future, but for now it’s a broad look.

“We’ll probably be able to predict the timing a little bit better than the exact location,” says Collins, “You can’t step on a location and say, ‘This is the next one to go,’ mainly because of variability in the soil.”

Variability not just in the type of soil, but in whether it’s had a chance to dry out between storms. If it has, a heavy rainfall isn’t as hazardous.

Right now, Collins says their sensors show soil moisture levels that are high and staying high.

“There hasn’t really been too many drying out periods in between storms; we’re getting storms every couple of days,” he says. “The next part of the equation is, will there be a storm with high enough rainfall intensities to actually do something?”

Since the risk of landslides is related to how much rain falls in a 24-hour period, people wanting to prepare can check the National Weather Service hazard warnings for detailed information on major storms and other weather events. Experts also recommend having an emergency plan for yourself and your family.