For some businesses, the first introduction to Prop. 65 is the arrival of a “60-day notice,” informing them that they are in violation of Prop. 65 and in danger of being sued.

That’s what happened to Bette and Manfred Kroening, who own Bette’s Oceanview Diner in Berkeley. In 2006, they received a 60-day notice saying that small amounts of lead had been detected on bottles of Original Nehi Grape soda the diner served.

By law, the diner should should had a Prop. 65 sign posted, warning customers about the lead, the letter said.

Bette Kroening noticed a name on the letter.

“I saw this name Whitney Leeman all over the place and that this was a person involved up and down California, I felt, looking for opportunities to find people like us to make some money. That’s what I thought.”

Kroening had stumbled onto a small and little-known subculture of people who have a special relationship to Proposition 65.

They’re called private enforcers, and they send out letters like the one Bette received to dozens of businesses a year.

If the business and private enforcer reach a settlement, the business owner typically does three things: put up a Prop. 65 sign or remove the toxic chemical, pay the enforcer’s attorney fees and costs and also pay a civil penalty.

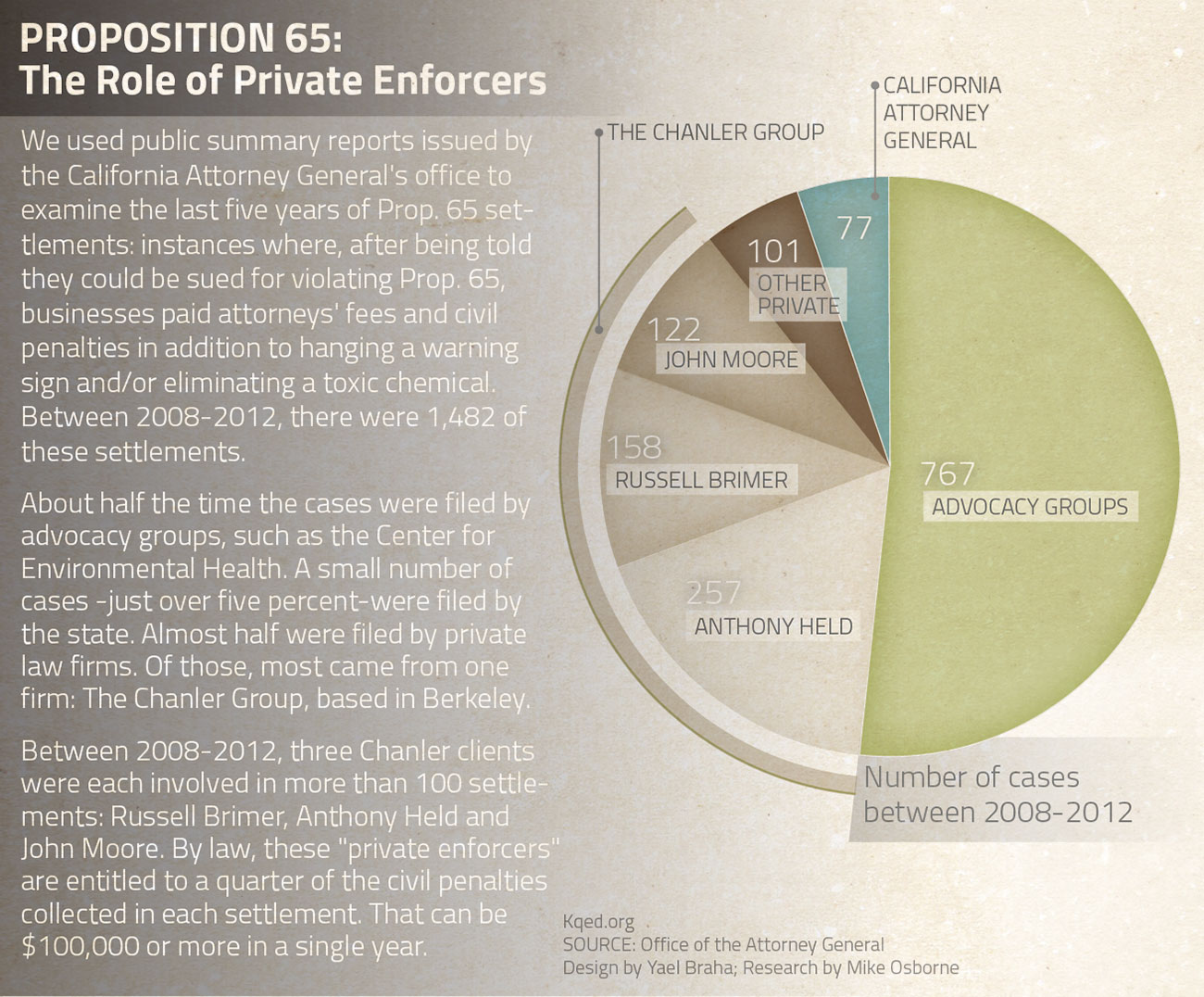

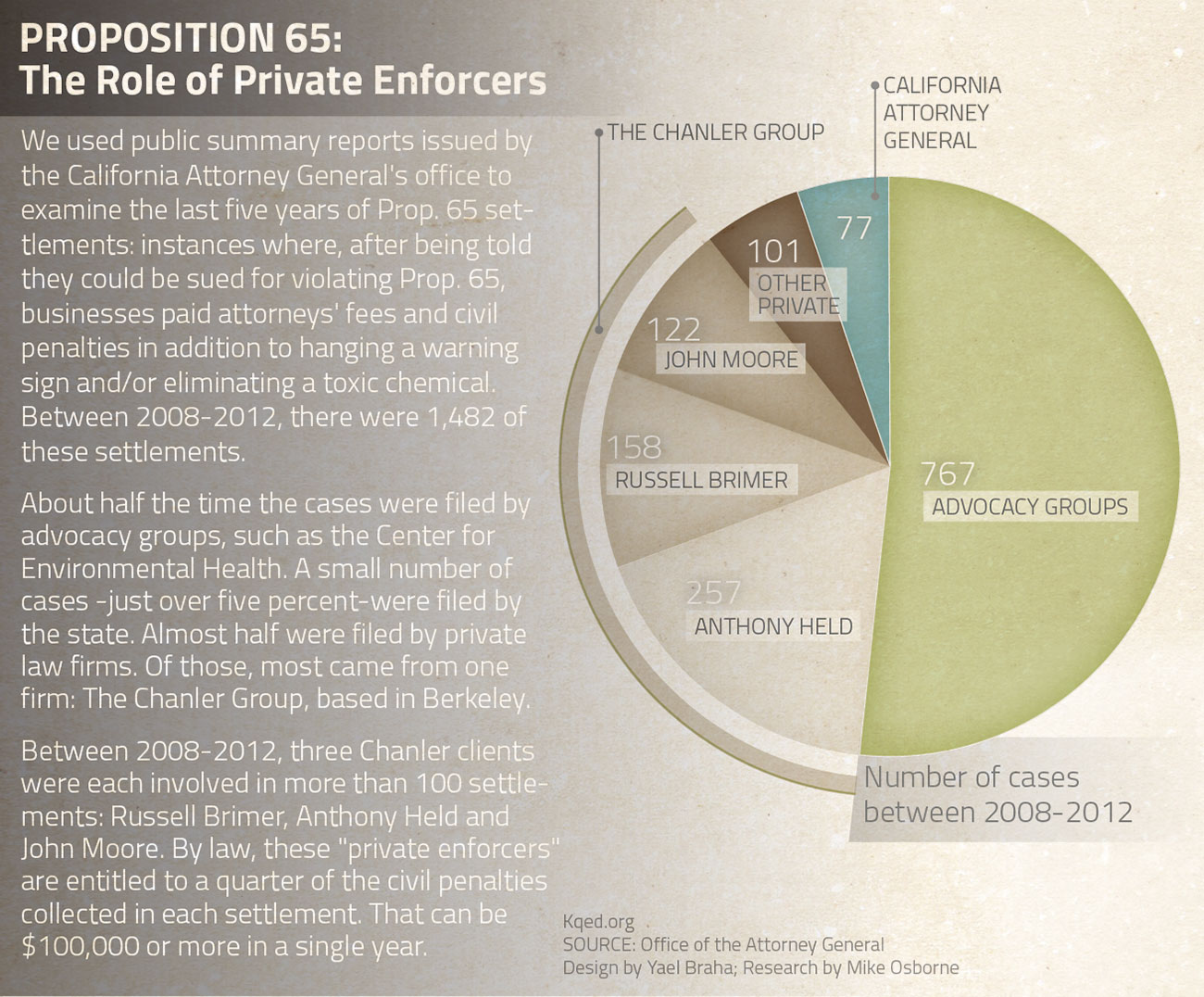

Of that penalty, 75 percent goes to the state, and 25 percent goes to the private enforcer. For the most active private enforcers, this work can top $100,000 in a year, according to a state database, run by the Attorney General’s office, which tracks all Proposition 65 cases. Typically, a much larger amount goes to the law firm that represents the private enforcer.

Attorney Cliff Chanler heads The Chanler Group, a Berkeley law firm that represents some of the most active private enforcers. Prop. 65 has been “more than a majority of our firm’s case load,” he says.

Chanler says the Bette’s Diner incident was part of a larger and successful case against the Dr. Pepper Bottling Company of West Jefferson. And in the end, Bette didn’t have to pay a fine. “We settled with Dr. Pepper, achieving a great public benefit, raising $1,000,000 [for the state, in penalties] and releasing Bette’s Diner of all liability.”

In 2007, Chanler received a letter from the Attorney General’s office, expressing concern over how such cases had been handled. “Your clients have collected significant sums of money from businesses that have little or no liability for past violations, and an amount of attorney fees that appears to exceed a reasonable amount,” the letter read.

Says Chanler, “we fight the good fight against people who have a lot of resources and have put millions of millions of different items on the marketplace without alerting the consumer so they can make a choice.”

Fighting the good fight can be pretty lucrative.

According to the California Attorney General’s public database, Chanler’s firm has collected millions of dollars working on Prop. 65 cases over the years. His clients, like Whitney Leeman, can make hundreds of thousands of dollars.

That’s red meat to critics of Prop 65, such as John Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association.

“Clearly they’ve set up a cottage industry,” says Coupal. “You have a law that’s essentially been rendered meaningless except for those who are able to engage the judicial process to make themselves a very good living.”

I wanted to learn more about private enforcers and what motivates them. I started with Whitney Leeman, who sent the letter to Bette’s Diner seven years ago

According to the state database, Leeman’s filed 232 notices to businesses across California. She’s gone after pthalates in greeting cards, carcinogens such as benzoanthracenes in grilled hamburgers and lead in eye shadow. This work has netted her somewhere in the neighborhood of three hundred and fifty thousand dollars.

Leeman also works for the California Air Resources Board, a state agency that regulates air quality.

This doesn’t sit well with John Coupal.

“She’s out there on the one hand working for the regulatory agency, but also pursuing a personal agenda,” says Coupal. “So it does strike me as presenting a pretty clear conflict of interest.”

Leeman declined to be interviewed. But in response to our questions, Chanler sent an email with Leeman’s “thoughts as interpreted and conveyed by me.”

The email said there’s no conflict of interest that Leeman’s aware of. She does her Prop. 65 work outside of office hours, and the work hasn’t involved air quality issues.

I tried to speak to another of Chanler’s clients: Russell Brimer. According to the state database, Brimer has sent out 1,057 notices since 2004 and earned at least $600,000 in that time.

Chanler said Brimer didn’t want to be interviewed, adding that Brimer is 41, lives in Emeryville, and works as a private investigator and security guard.

Chanler set up a conference call with another of his clients: Anthony Held, who has a PhD in environmental engineering from UC Davis.

“My motivation in this field,” said Held, “is to identify and reduce the source of environmental pollutants and the harm that can come from them.”

According to the database, Held has filed 720 cases and earned at least half a million dollars. Held says he’s proud of the work he’s done.

“As to whether people would indicate ulterior motives, I think that could be said of any profession,” Held told me.

Private enforcers are “possibly an efficient form of enforcement,” says David Engstrom, an associate professor at Stanford Law School.

He says there are two ways a law like Prop 65 could have been written. One, establish an office of government prosecutors to enforce it. But often, Engstrom says, they drop the ball.

“Government regulators may be too lax,” he says. “Prosecutors [may] be unwilling to bring cases that it would be good for society to have brought.”

That leaves the option number two, the private sector, including advocacy groups and private individuals like Russell Brimer and lawyers like Cliff Chanler.

Engstrom says the risk here is too much enforcement: too many suits, including some that may not be in the public interest. This is “just throwing spaghetti at the wall and hoping something will stick,” as Engstrom describes it.

This summer in Sacramento, lawmakers say they’re looking for a happy medium. One bill, AB 227, sponsored by Democratic Assemblyman Mike Gatto from Los Angeles, passed the State Assembly 71-0 in May.

AB227 would give certain businesses, including restaurants, a 14-day grace period to put up a sign and avoid big penalties and attorneys fees. That would mean less money for citizen enforcers.

A broader proposal from Governor Jerry Brown would, among other things, cap attorney’s fees to make Prop 65 less lucrative for lawyers.