Who would get water from the tunnels?

The tunnels would be part of the state’s major water system that serves about 25 million Californians, from the Bay Area to San Diego. Built more than 50 years ago, the network of reservoirs, canals and aqueducts stretches hundreds of miles.

It’s designed to fix a tricky problem that state planners ran into a century ago. Most of the rain and snow falls in Northern California, but most of the state’s population (and many farms) reside in Central and Southern California.

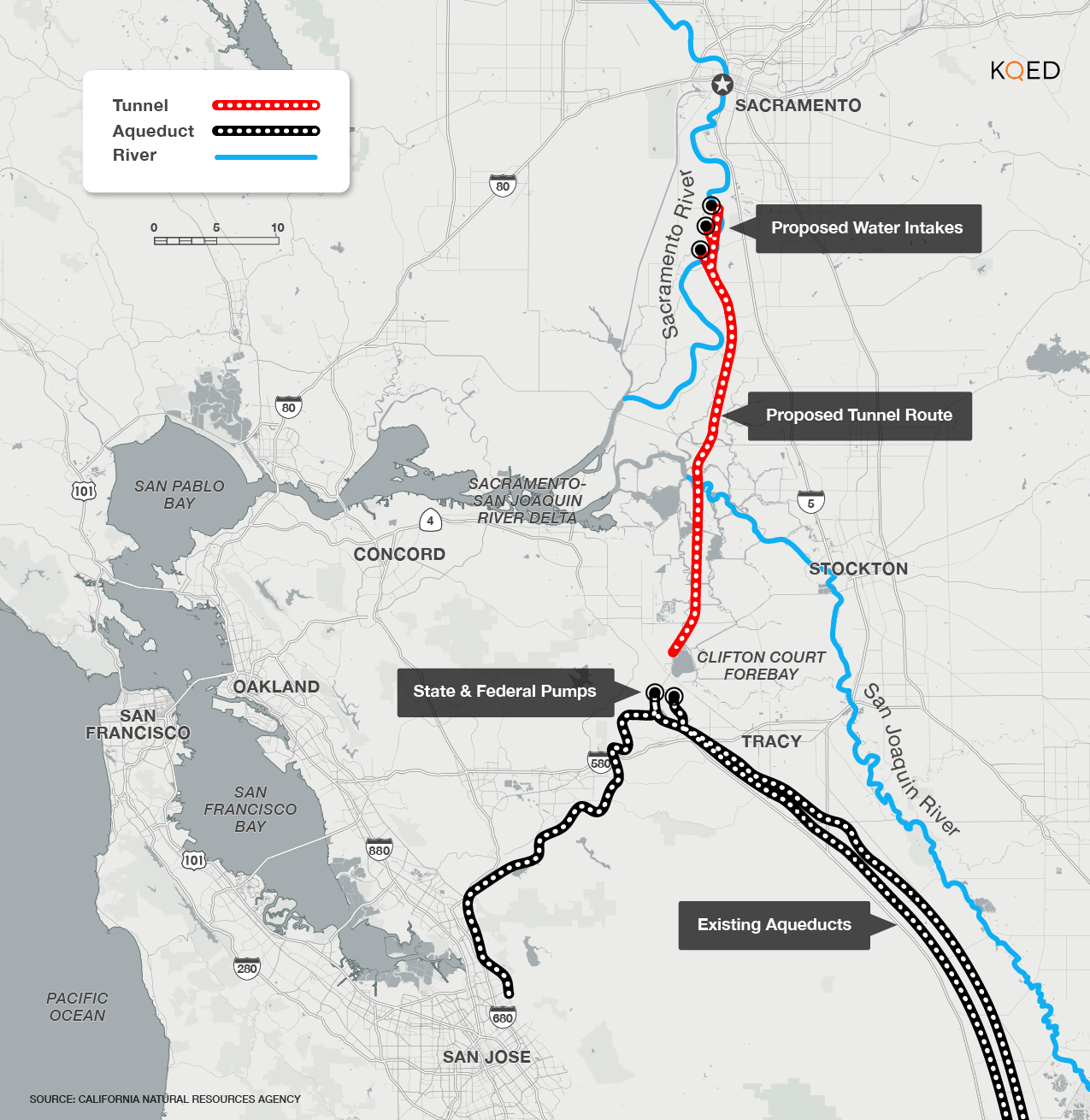

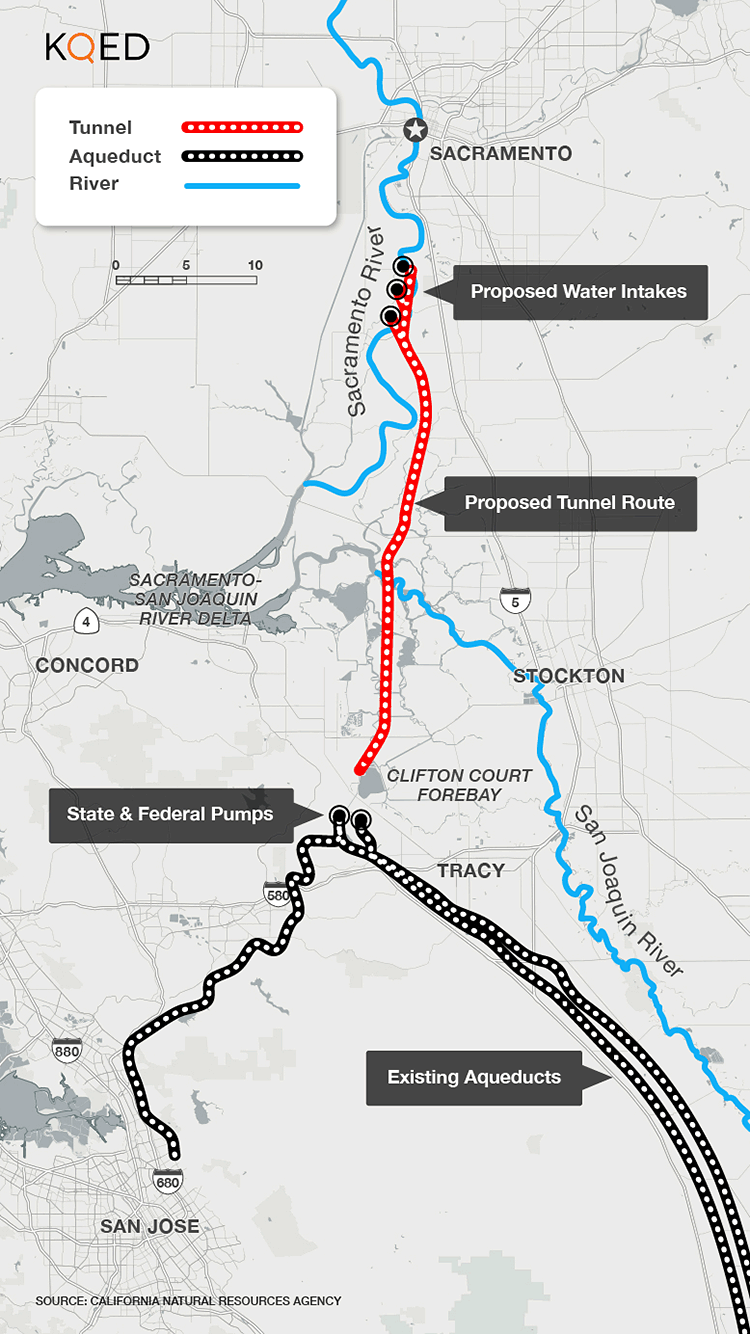

Proposed Route of Delta Water Tunnels

Huge underground project would divert water from the Sacramento River for export to Central and Southern California.

Why Does the Brown Administration want to build them?

The recent drought may have brought water battles to the forefront, but those battles are a perennial feature of California politics. That’s because the central hub of this water system, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, is in bad shape.

Water is drawn from the Delta by two massive pumping facilities that can move millions of gallon per minute. They’re so powerful that they’ve been shown to entrap endangered fish, like Chinook salmon and Delta smelt. When those species are at greatest risk, regulations require slowing down the pumps, potentially limiting how much water reaches cities and farms.

The twin tunnels would take water from farther north near the Sacramento River, and deliver it to the pumping facilities. State officials say that would make the water system more reliable, because the pumps would be used less, avoiding the impacts on endangered species.

How much would the tunnels cost and who would pay for them?

They aren’t cheap. Construction could cost $14.9 billion. Add in mitigation costs for construction impacts, operations and maintenance and the tab runs to about $17 billion over 50 years — and that doesn’t count paying off the bonds that would finance the project.

Ostensibly, it would be paid for by the water agencies that get the water, including urban water districts in the southern Bay Area and Southern California, as well as agricultural water districts in the Central Valley. Those agencies would have to raise water rates or possibly property taxes to cover the cost.

Who is against building the tunnels?

A lot of people. Residents that live in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta don’t want a major construction project in their backyard and are concerned it could affect their water quality.

Some environmental groups say the tunnels, as they’re designed now, could make things worse for endangered salmon and other fish as too much fresh water is removed from the ecosystem, though there are other issues as well, like habitat loss and invasive species. Environmentalists say that the tunnels would simply continue the trend of removing too much fresh water.

So how much water will the tunnels take out of the Delta?

Hmm, good question. State officials have proposed a range of scenarios. At one end of the range, water users could see more water delivered to them. At the other end, they’d get less, but more would be left in the ecosystem.

But here’s the hitch: several of the water agencies that would pay to construct the tunnels have said they can’t justify the costs if there’s a chance they’ll end up with less water.

So, why should I care about this?

California’s water problems aren’t going away. There will be more droughts, more conservation rules and more challenges ahead, especially with climate change.

The state’s water system, as ambitious as it was a half-century ago, can’t keep up with current (let alone future) demands. So whether fixing that problem involves massive water tunnels, or simply finding ways to do more with less water, Californians are going to have to do something.

Who will decide if the tunnels get built?

Now it’s up to state and federal agencies. The State Water Resources Control Board is beginning hearings to answer two questions: will the tunnels impinge on anyone else’s right to use water and will they harm endangered species? Those hearings could go on for quite a while, maybe until mid-2017.

State and federal wildlife agencies will look at whether the project will harm endangered salmon and Delta smelt, as well as other species. And in their review, they will determine how much water the Delta tunnels can deliver in order to ensure that species don’t go extinct.

That decision could determine whether water agencies are in or out, ultimately deciding the fate of the project. Oh yeah, and the whole thing is likely to end up in court, no matter what the decision.

What about a public vote? There’s a November ballot measure that would require votes for big infrastructure projects.

True. If passed, Proposition 53 would require a public vote on projects backed by state-issued revenue bonds over $2 billion, including this one.