Twenty six nautical miles outside the Golden Gate, the spindly peaks of the Farallon Islands bobbing in view, the R/V Fulmar research vessel has made space for me to observe how researchers carry out their commitment to keep our oceans healthy.

Still working on developing my sea legs, I clamber up a ladder to the top deck, and as gingerly as possible, stumble to the bow of the boat.

This vessel is run by a marine conservation partnership called ACCESS, or the Applied California Current Ecosystem Studies. The crew, comprised of marine researchers from the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the non-profit agency Point Blue, is scanning the horizon for signs of life, which they are finding in abundance.

On this brilliant July afternoon, the scientists on board are deploying nets and hauling in microscopic forms of life from the ocean. They pull in tiny krill and their even tinier food source, plankton, the marine plants that form the foundation of the ocean’s food chain and shed light on the health of the vital marine habitat off the coast of Northern California.

One researcher records the number of wildlife that surround the boat, while the others gaze through binoculars and call out species names as they see them — like puffins, white-sided dolphins and red-necked phalaropes.

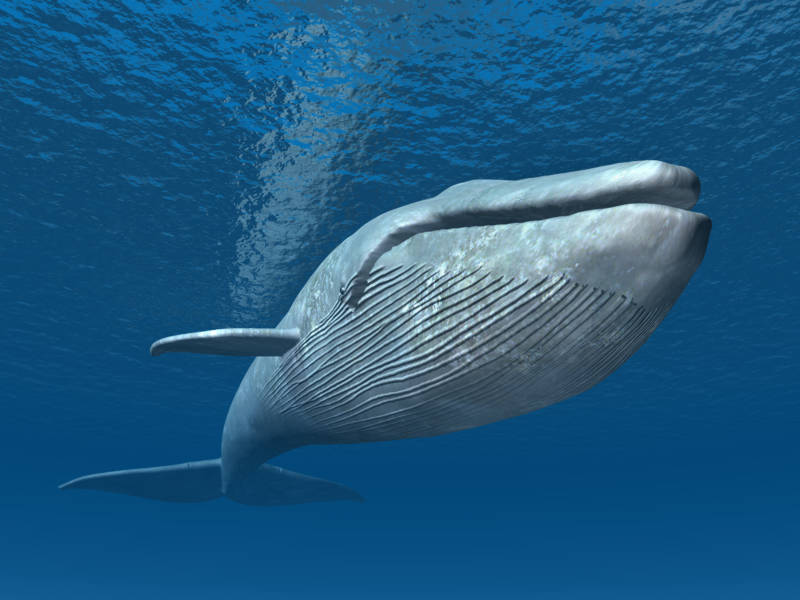

First mate Marshall Stein offers me his front-row swivel seat and moments later, there’s a wave of excitement as one, two, three, four blue whales come into focus. Mouth agape, I stare at the largest animals the planet has ever seen as they spout water from their blowholes, the silhouettes of their majestic blue backs against the backdrop of the Farallon Islands. I am speechless. So are the marine biologists. This is extraordinary, not only for a novice like me, but also for seasoned researchers.

Since April, there have been a record number of whale sightings in San Francisco Bay—including this breathtaking encounter filmed by a local kayaker.