Image Credit: Tania Larson/USGS

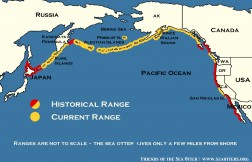

Imagine sea otters drifting and diving in San Francisco Bay and swimming in the abundant pickleweed of the salt marshes surrounding its waters. Up until the early-1800s, that would have been a common sight. They’ve been long gone in our area, since the 1840s when fur hunters trapped the last of the surviving bay population around Corte Madera Creek. A remnant population, discovered near Big Sur in 1938, has been slowly expanding from an estimated 50 otters. Southern sea otter populations span from east of northern Santa Barbara to around Pigeon Point, and includes a small population on San Nicolas — the westernmost of the Channel Islands.

The annual Southern sea otter population count, just released, showed a complex but hopeful trend. The population appears to be increasing slightly overall, but it still hovers below the level needed to delist the federally threatened species. The southernmost population appears to have the highest mortality from great white shark bites. They’re not eating them, just tasting, but the otters can’t survive a bite.

The largest population, in Elkhorn Slough on Monterey Bay, is the object of a new study by UC Santa Cruz professor Tim Tinker of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and a team of scientists from a collaboration of agencies and non-profit organizations.

Dr. Tinker commented, “Otters are an important species to study. They’re an apex predator and have a direct bearing on the health of the ecosystem.” The preliminary data from the Elkhorn Slough otter study reveals some interesting information.

Tinker stated, “In the the slough, otters’ primary foods are crabs, clams and worms, as well as snails and other benthic species. The data so far noted that areas in the slough populated by otters had healthier seagrass beds. Since with fewer crabs, the isopods and sea slugs could graze the algae off the grass, promoting better seagrass growth.”