But TB persists among the homeless. And on LA's Skid Row, where crowding and unsanitary conditions help spread the disease, it’s made an alarming advance.

Since 2007, officials have identified some 94 cases in the area, 77 of them among the homeless. Half of those cases have been reported in the last two years. So far, 17 people have died, said Robert Kim-Farley, director of communicable disease control and prevention for the Los Angeles County health department.

In February, county, state and federal health authorities announced a coordinated effort to contain a persistent outbreak in the downtown neighborhood dotted with cardboard shanties and tent encampments.

Kim-Farley said through a genetic analysis, researchers have established that a unique strain of tuberculosis is centered on Skid Row, and is being passed from person to person there. With intensive medication, TB is curable. But authorities estimate that more than 4,500 people may have been exposed to the disease.

The challenge is to find out who they are and to get them to agree to treatment. That’s where the UCLA School of Nursing’s Public Health Center fits in.

Homeless people can be suspicious or even fearful of government efforts to hep them, Kim-Farley said. “So these community providers that are known and trusted by the community are very important.”

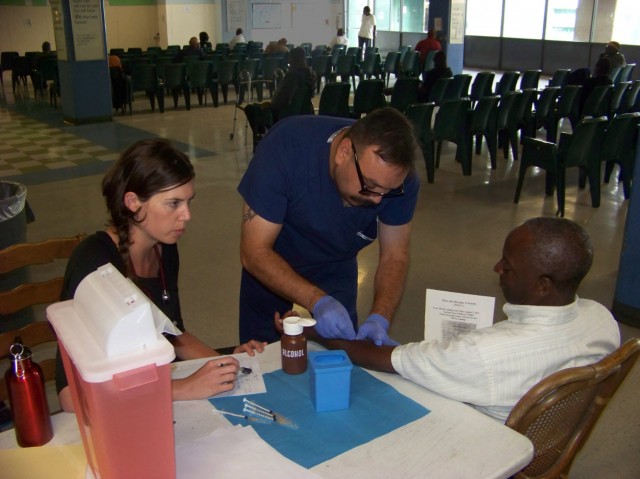

One recent morning a UCLA team visited the Union Rescue Mission in the heart of Skid Row and set up a table laden with test kits in the Mission's dayroom.

Of the 15 men who lined up for tests, most said they’ve heard little about the outbreak and were only getting tested because it’s mandatory for anyone staying in the Mission dormitory for five days or more.

But, Matthew Morales was an exception. He knew the risks.

“You have people coughing right in your face down here,” he said. “I’m a big fan of those sanitary wipes to try to kill bacteria, but I don’t think that’s going to help much with something like TB. So, when I get a chance like this to make sure I’m OK, I’m going to take it.”

Andy Bales, the Mission’s chief executive, said a lot of people are both worried and poorly informed.

“Early on, I talked to a woman on the street about coming in, and she said, ‘No, I don’t want to come in to the Mission. I might get TB,’” he said.

“She’s certainly more at risk being on the street than she is at the Mission where people are screened and people are receiving health care. But the information gets lost, and people become misinformed.”

Mary Marfisee, the Health Center’s medical director, said she and her students are doing all they can to disseminate facts, and to test as many people as possible.

“Our people at the Mission know who’s there every day, so if they see somebody they don’t know, they ask them if they want a test,” she said.

The Health Center also enlists the aid of medical students from a program jointly run by the UCLA Geffen School of Medicine and Drew University that trains physicians to serve the homeless and poor.

Third-year Drew student Cara Quant said she’d never seen a positive TB test before she started at the Mission. So far, out of the 100 people she’s helped to screen, four results have come back positive, Quant said.

Marfisee said before county officials announced the outbreak in February, she sometimes had trouble obtaining treatment for homeless people known to have been exposed to tuberculosis but whose infection remained “latent,” or largely asymptomatic. Since then, county health officials and Skid Row community providers have started to work together, including jointly developing a treatment regimen that can be completed in weeks instead of months. That’s much better suited to a transient population, Marfisee said.

The UCLA team includes medical assistant Antonio Vera, who was homeless and a patient at the clinic before Marfisee encouraged him to go to school to train for his current job with the university.

“He’s very astute and sensitive to people’s needs,” Marfisee said. “They may come by for a TB screening, but often, within a couple minutes, Antonio’s able to pick up on some other health condition that needs attention, and we’re able to attend to that, too.”

“A lot of people want to get out of here, just like I did,” Vera said. “That’s why I pursued the knowledge of case management, so I could help them climb up the ladder and get out of this hole.”