About 11 percent of the women had "suspicious" mammograms and were subjected to further testing, including repeat mammograms, ultrasounds and needle biopsies. For nearly all these women — 98.6 percent — cancer was not confirmed in further testing.

When Mandl projects this percentage of false alarms to the entire female population over age 40, he estimates that the U.S. spends $2.8 billion each year on follow-up tests for suspicious results that turn out not to be cancer.

And even when cancer is detected, some of those tumors might be of low risk to the patient -- slow-growing and not likely to become invasive or life-threatening. But once suspicions are raised, Mandl says, overtreatment is often the result. "Overtreatment is bad," he says. "That's mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation, in women who may not have needed any medical treatment at all."

For example, patients diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ can face radiation, chemotherapy and even mastectomy despite the fact that the cancer is noninvasive.

Mandl estimates that the cost of overtreatment adds up to $1.2 billion each year, resulting in a grand total of $4 billion in unnecessary spending annually.

And it's not just the financial cost that's a problem. When a woman receives a suspicious mammogram result, it often creates psychological stress and anxiety, Mandl says.

Still, some researchers have issues with Mandl's findings. Dr. Richard Wender, of the American Cancer Society, says the study overestimates the cost of unnecessary testing and incorrect diagnoses. And he says it fails to consider the proven benefits of annual mammograms.

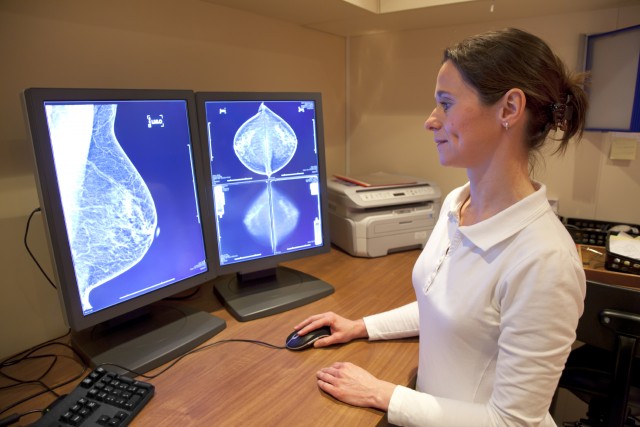

"Mammograms are the most effective way we have to find breast cancer before anybody can feel it, before you're aware of it," Wender says.

He points to studies showing that mammograms reduce the risk of dying from breast cancer by 20 percent. "So whenever we're doing decision-making, either as policymakers or just between one woman and her doctors, it's critical to look at ... benefits as well as downsides," he says.

The American Cancer Society recommends yearly mammograms for women starting at age 40. However, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that screenings start later, at age 50. That's because younger women, between 40 and 49, are more likely to receive false-positive results.

Harvard's Mandl would like to reduce the number of screening mammograms even further. He suggests that screening be based on a woman's overall risk factors for breast cancer, including family history, obesity and breast density, as well as age.