In 1966, Variety called Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls, now a cult classic, “a pointless, excruciatingly dull three-and-a-half hours.” Variety isn’t entirely incorrect about the three-and-a-half hours of excruciating dullness, but it’s not fair to equate that with pointlessness. The film, which is playing at the Castro Theatre on November 6, has its place in cinema history and is not without purpose.

Chelsea Girls is a collection of twelve vignettes shot in various rooms in New York’s landmark Hotel Chelsea. The “stories” — a term used loosely since most lack a traditional narrative structure — are each approximately thirty minutes long and two are projected side-by-side at all times. There is only one audio track, which always renders one vignette silent. The audio switches between the two video channels, but some vignettes are entirely devoid of sound.

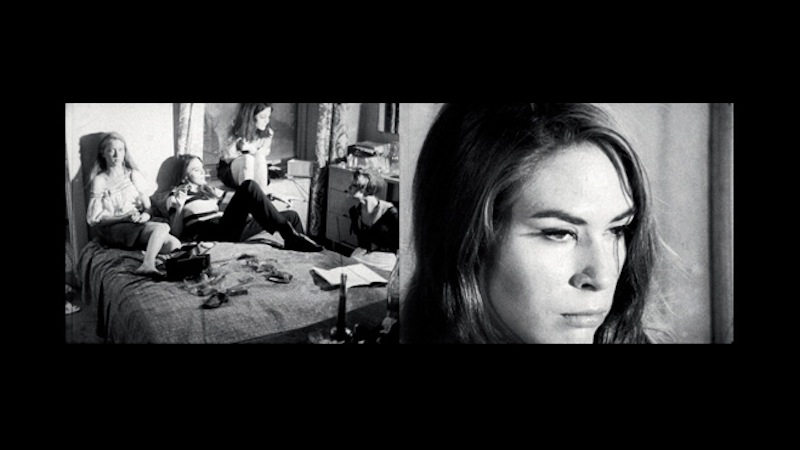

The opening scene includes a vignette showing singer Nico combing her hair, peering into a mirror, and calmly conversing with a man and a child. The camera moves around the room without any discernible order, cueing the visual style of the following 200 minutes. On the other channel a man played by Ondine, an actor who appeared in many of Warhol’s films, chats with a character played by Ingrid Superstar in a dark room. The nature of their conversation is unknown until the audio switches to reveal Superstar’s character confessing to either a former priest or a fake priest, depending on which declaration one chooses to believe. The rambling, improvised, and confrontational confession provides the bulk of the laughs in Chelsea Girls, as Ondine and Superstar bicker about grammar, ear piercings, deodorant, and their first sexual experiences. The vignettes grow increasingly hostile, as Warhol’s superstars fight amongst themselves, use drugs, and chew each others clothes.

Throughout the film, viewers must choose which channel to pay attention to and the easiest choice is the channel with accompanying audio. But with some pairings, the action in the silent channel draws the viewer’s attention across the aural barrier. As one vignette begins, two men are smoking cigarettes in bed, one is in a bathrobe and the other in his underwear. The scene is usual enough, but at some point the shot widens and there are two women in the room. The change is missed if the viewer is watching the other channel that is accompanied by sound. Later, one of the women begins tying up the man in his underwear. Without sound, and often witnessed in fractured moments of attention, the logic of the events in this vignette are never revealed. Viewers can choose to create a narrative or just take in what they see as-is.

Having grown up at a time when Warhol was already written into art history and the surviving cast members were senior citizens, it can be difficult to intuitively feel the transgressive nature of the subject matter. I must remind myself that this was a different time, make assumptions about what was shocking to see on screen then, and place the film in historical context. On the other hand, a half century of experimental film and underground cinema doesn’t ease the blow of Chelsea Girls‘ cinematography or structure.