“I didn’t take this up for the poetry of it,” writes Rowntree. “I had no ambition to become a picturesque Lady-Gypsy. I honestly wanted to find out about California wildflowers. There was little written about them in their habitats and nothing at all about their behavior in the garden, so I made it my job to discover the facts for myself.”

And yet one of Rowntree’s most enticing traits, to me, was her embrace of a traveling, nomadic life. During the winter months, she lived in a house in the Carmel Highlands, with a view of the Pacific. The other six months were spent on the road, criss-crossing the state carrying only a sleeping bag, a camera, hiking gear, a flower press, seed bags, miner’s tools, and a few other things in her car. Quite often, she left the car parked, and set out on foot. “The best stands of native plants can be reached only on foot or by horse or burro,” she writes. “My car is purely a means of transportation to the vicinity of these places. No one who has not left the highway and followed out-of-the-way trails can have any conception of the poignant beauty of the haunts of California wildflowers.”

Eighty percent of Hardy Californians will be of interest only to gardeners, native plant enthusiasts, and amateur botanists (I admit to skipping many of the details about P. heterophyllus, L. exubitus, V. caeruleus, and so on). But between Rowntree’s floral descriptions is a biography worth paying attention to, and elegant little life lessons, whether she intended to give sage advice or not.

About the “contemned” Buckwheat, she writes: “Its roots system, like that of all of these alpine Eriogonums, goes deep underground, making a safe mooring against the fierce winds which beat across mountain tops, tapping supplies of moisture for the leaves and flowers.” The parallel is clear: Rowntree herself found her own personal deep roots in California wildflowers. It was an obsession that allowed her to rebuild a life committed to botany work and writing at the age of fifty-two, soon after a divorce left her broke and homeless in Carmel in the 1930s.

By 1932, she’d written over 100 articles about plants and gardening, allowing her to buy a plot of land in Carmel. She paid for the building of the house with the proceeds from her writing, and by bartering gardening skills with local craftspeople, according to her grandson Les Rowntree. The reinvention of her life is told in Hardy Californians:

It took adversity to bring me the sort of life I had always longed for. Not until after my domestic happiness had gone to smash did I realize that I was free to trek up and down the long state of California, and to satisfy my insistent curiosity about plants, to find them in their homes meeting their days and seasons, to write down their tricks and manners in my notebook, to photograph their flowers, to collect their seeds, to bring home seedlings in cans just emptied of tomato juice.

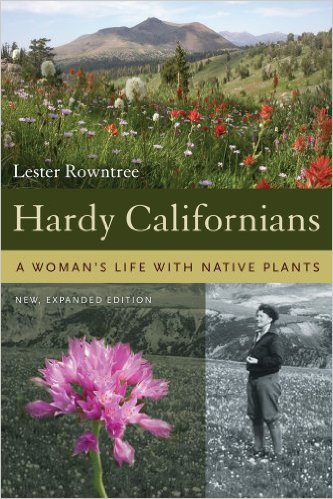

There’s a sense that, despite a domestic happiness “gone to smash,” Rowntree had actually never been happier, finally allowed the freedom to wander and catalog to her heart’s content. Like John Muir before her, Rowntree was known for taking off alone into the wilds of California: the desert, the alpine Sierras, and foggy coastal climes. She loved to sleep outdoors and once snippily told someone that the tent in one of her photos was only there to house her photography equipment. She preferred, always, to sleep only in a bedroll, under the night sky. I couldn’t help asking, as I read the book, why Rowntree didn’t gain the recognition accorded to John Muir, whose ardor for California’s expanses of vast nature she certainly matched. In fact, I found myself wishing that instead of attending Muir College at UC San Diego, I’d attended Rowntree College.

Rowntree was self-taught and never referred to herself as a botanist. Still, she went on to start a successful seed company, help found the California Horticultural Society with Alice Eastwood, the botany curator at the California Academy of Science, and additionally publish over 700 articles in places like the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. But Rowntree didn’t just write for money. According to her grandson, she immersed herself in the craft of it, working long hours in her study to perfect the sentences about her beloved plants. As a side hustle, she gave talks for ladies’ garden clubs.