We don’t have any photographs of the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn. The large-scale dramatic paintings executed after the fact were based on eyewitness accounts — though at times, not even those. Distorted visual representations of “Custer’s Last Sand” appeared in “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West shows starting in 1888 and continued, with Errol Flynn playing a highly fictionalized (and dashing) Custer in the 1941 hit They Died with Their Boots On.

But in the low light of the Cantor Arts Center’s second-floor gallery, a true eyewitness account of the battle is on display in Red Horse: Drawings of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The 12 graphite, colored pencil and ink drawings on blank ledger paper illustrate one man’s memories of the two-day battle. The artist is Red Horse, a Minneconjou Lakota Sioux warrior who experienced firsthand the victory of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapahoe forces over the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry.

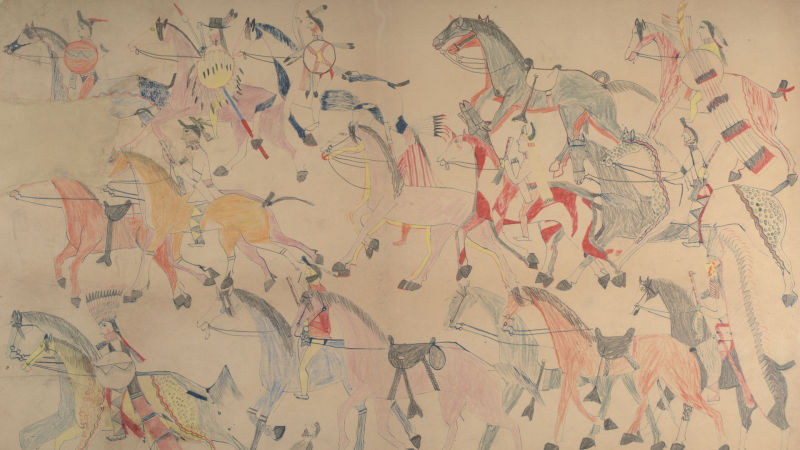

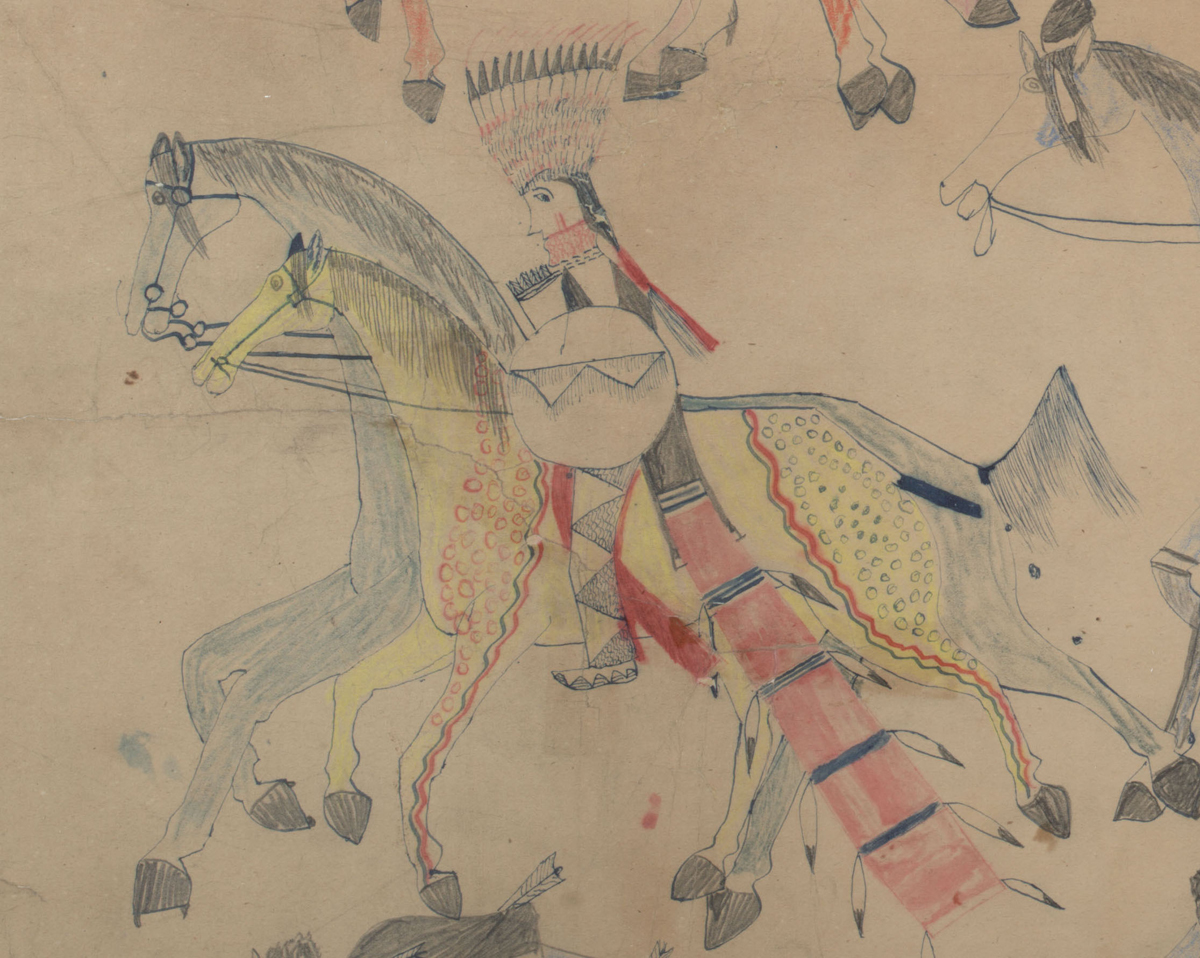

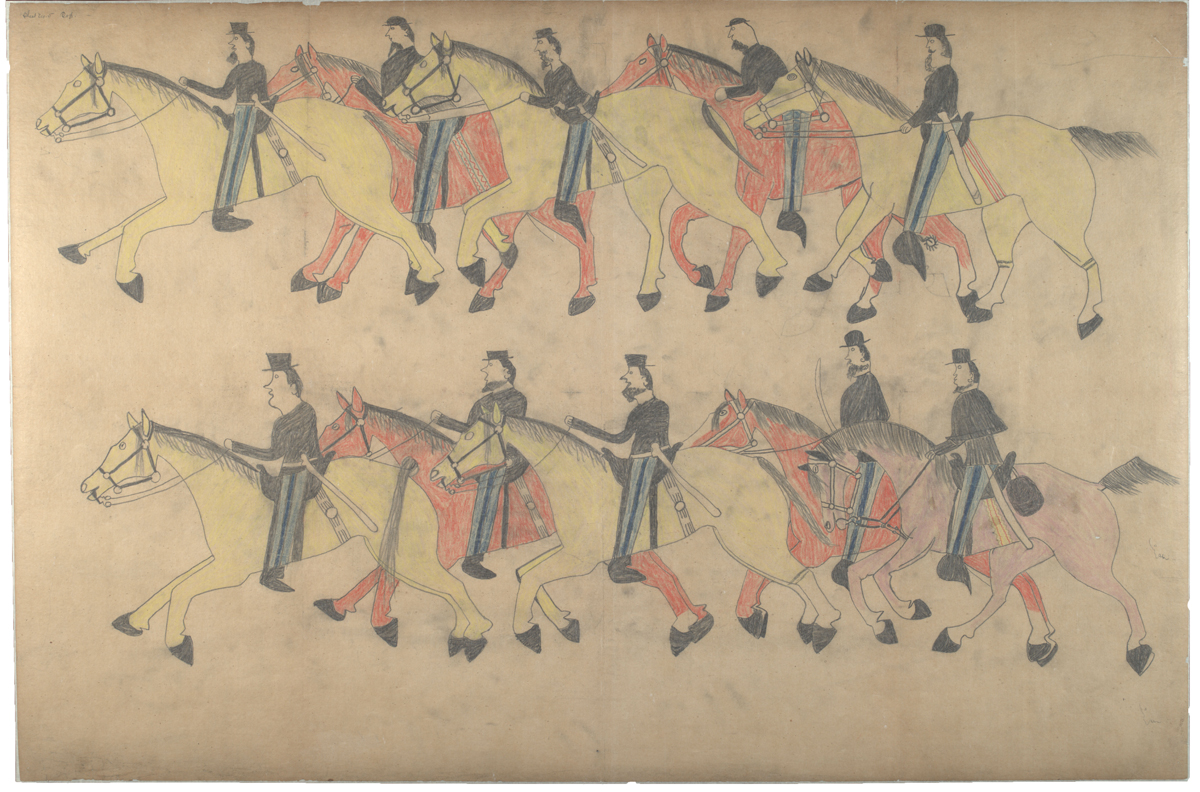

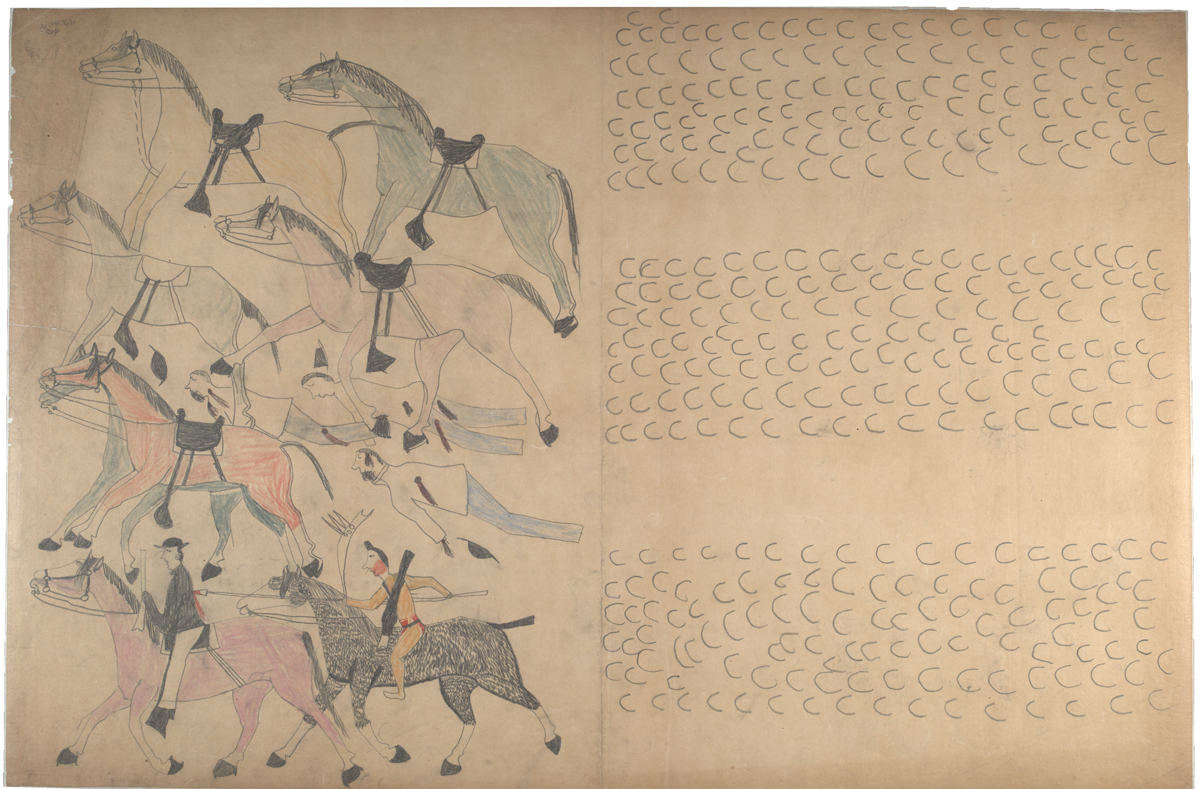

In wordless detail, Red Horse depicts uniformed cavalry soldiers advancing on horseback from right to left. Then, three orderly rows of tipis. Then, Native American warriors and hundreds of hoof tracks. The battle that follows is scene after scene of jumbled and extreme violence — both horses and men fall to the ground dead. In the final drawing presented at the Cantor, the victors — Native Americans carrying what were once cavalry rifles — ride their own horses bareback and lead what were once cavalry ponies (recognizable by their saddles and long tails) from right to left across the page.

Red Horse created the drawings in 1881 to accompany his sign-language testimony of the battle, a testimony likely gathered not for historical or artistic reasons, but for the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology 1894 study of Native sign languages and “Picture-writing of the American Indians.” His 42 drawings entered the Smithsonian Institution’s National Anthropological Archives and remained there for 135 years, leaving storage only a few times for short exhibitions.

“They’ve just been in drawers,” says Stanford senior Sarah Sadlier, a student research assistant who was integrally involved, along with her professor Scott D. Sagan and Cantor curator Catherine Hale, in selecting the drawings now on display at the Cantor. Sadlier, like Red Horse, is Minneconjou.

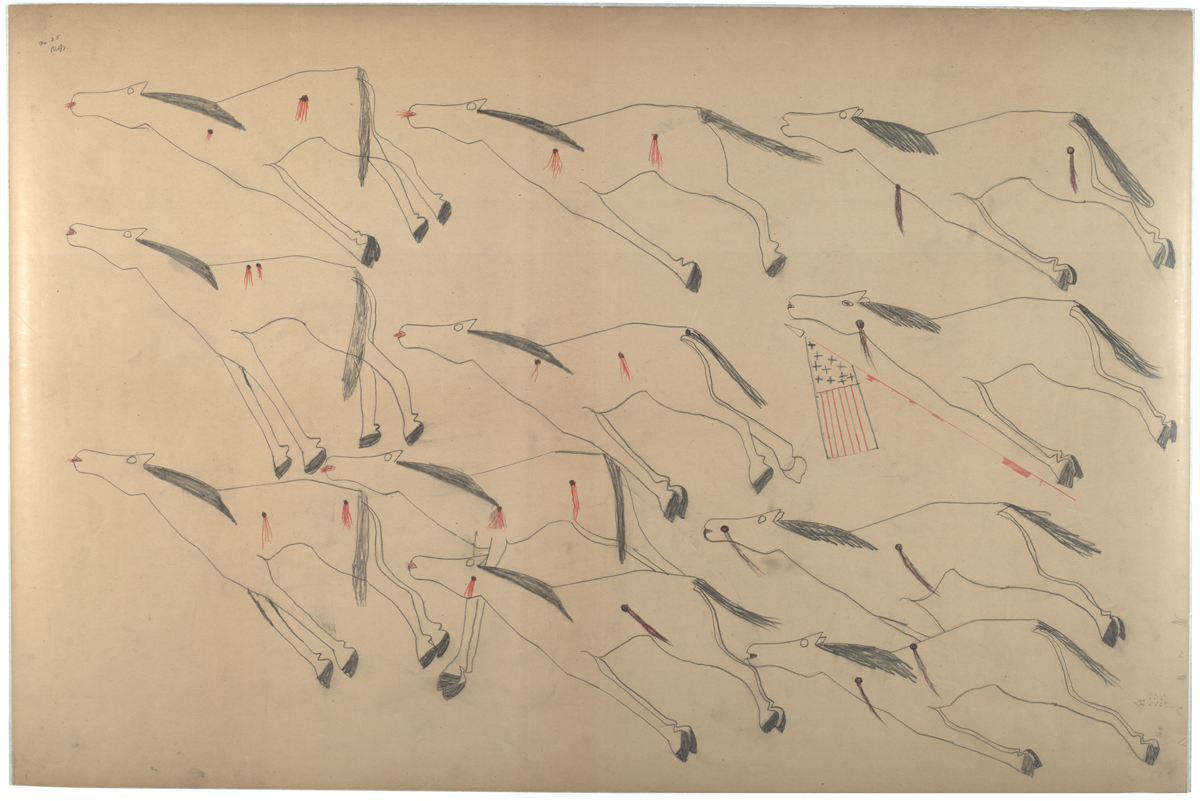

Red Horse’s eye for detail is unsparing. Soldiers sport different styles of facial hair. A white man in civilian clothes — potentially Custer’s brother or nephew — lies dead near an upside-down American flag. He captures differences in garb and decoration, but also the gory realities of battle: fallen soldiers on both sides, dismembered limbs, scalped bodies and an entire page devoted to dead cavalry ponies.