In the trailer for his 2006 film Babel, director Alejandro González Iñárritu includes a voiceover, one reciting a well-known passage from the Book of Genesis that tells of a unified language and pervasive understanding that man enjoyed prior to the Flood. That clarity, that point of agreement was troubled when dissimilar languages — understood here as a metaphor for different identities and interests — were introduced and the disparate tribes with which we associate were formed. Iñárritu’s inclusion of the voiceover is a predictable cinematic trope, but it raises issues about what and how we communicate, and how that dialogue is often overwhelmed by other concerns. Electronic Pacific, which opened at SOMArts on July 11, takes up the increasingly digitized exchange of art and language in the work of eighteen artists that span the complex divide between countries around the Pacific Rim.

The main gallery at SOMArts is not the easiest space to curate, given the institution’s broad mission and it’s unusual architectural footprint. It could easily look or feel crowded with multiple 3D objects vying for viewer’s attention. For Electronic Pacific, gallery curator and director Justin Hoover creates a very manageable experience, one that permits audiences to move through the space without the worrying sense of tripping over or backing into the objects on display.

Thom Faulders and Lynn Marie Kirby, The Crystalline World: SUBHEDRAL, 2013.

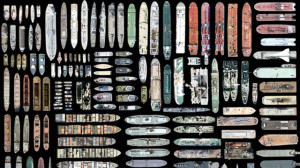

Presentation strategies are central to this exhibition, including Lynn Marie Kirby and Thom Faulders’ The Crystalline World: SUBHEDRAL, a commanding sculpture crafted from laser cut foam that invites viewers to experience the piece from both inside and out. The small, uniform blocks, inspired by a series of walks and encounters around the Bay Area and in China, reflect Kirby’s interest in salt mining and its environmental and economic impacts worldwide. Taken further, Kirby’s work could represent the stacked shipping containers that carry commercial goods across the Pacific Ocean in an uninterrupted cycle of production and consumption that irrevocably binds east and west.

Videos by Laura Hyunjhee Kim

At the center of the gallery, three full-size shipping containers are utilized to create micro viewing environments for installations by Lauren Hyunjhee Kim and Marya Krogstad. Kim’s multi-channel piece, which combines autobiography, art historical references, and mass media in an examination of how meaning is communicated textually and visually, is by far the loudest and funniest piece in the exhibition. Watching the old school monitors on which the six short videos are looped, we see the artist in multiple scenarios, but it is nearly impossible to hear what she is saying. While I would like to have heard more of the artist’s deadpan humor, the point, at least in part, is that we can’t hear what she is saying over the virtual wall of noise that is created.