It’s nearly the end of 2017. Thank goodness that’s over, I think, quickly followed by: What new horrors will 2018 bring?

Speculative nonfiction aside, of all the things that happened this year, not all were terrible — especially when it comes to art. Art did what it does best: reflect, complicate and provide respite from the daily onslaught of local, national and global news. And Bay Area art continued to thrive — despite housing shortages, community losses and the crushing sense that we are actually living in the end times.

What follows is a non-hierarchical, highly personal, idiosyncratic list of my favorite moments from a year of art that filled me with local pride, and maybe even hope.

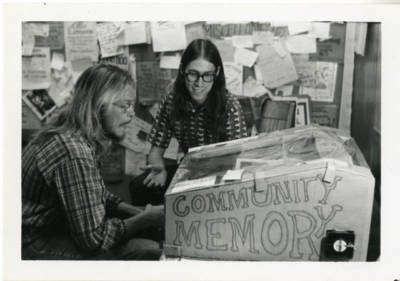

Best Obligatory Summer of Love-Related Exhibition: Hippie Modernism

Did you know 2017 was the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love? Nearly every Bay Area institution put on their version of a Haight-Ashbury heyday retrospective. Some were better than others. But the best of the bunch was BAMPFA’s Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia. Filled with tangible examples of counterculture art permeating everyday life, Hippie Modernism managed to take stock of the past while still speaking to the present — eschewing nostalgia in favor of highlighting the era’s still-inspiring radical spirit.

Best Event to Take Place in Total Darkness: The World According to Sound

In early March, a friend and I biked to LightHouse for the Blind’s newish Market Street headquarters for an hour-long audio experience in total darkness. Surrounded by speakers, and with sleep masks over our eyes, we traveled through the human bloodstream, across moaning bridges, deep into the past and far into space courtesy of The World According to Sound, a radio show created by local sound enthusiasts Chris Hoff and Sam Harnett. Our location within LightHouse made the event all the more meaningful: In that room, we shared an experience that transcended sight, sparking excited conversations within a newly formed community of listeners.

Best Permanent Collection Addition: Revelations

Anyone who’s visited the de Young in recent months has likely basked in the glory that is Revelations: Art from the African American South, an exciting and very necessary addition to the Fine Arts Museum’s permanent collection of American art. Among the paintings, root and branch sculptures, yard show metal works and Gee’s Bend quilts is my personal favorite: Ronald Lockett’s painted tin and wood wall piece, England’s Rose. Made in 1997, the assemblage remembers Princess Diana, who broke through boundaries of fear and misunderstanding in 1987 when she shook the hands of HIV/AIDS patients in a London hospital. Lockett himself died from complications of HIV/AIDS a year after the work was completed.

Best Pairing in an East Bay Museum: Over the Top

For many art viewers like myself, the Oakland Museum of California’s Over the Top: Math Bass and the Imperial Court SF was an introduction not to the hard-edged and infinitely pleasing paintings of LA-based Bass, but to a local organization that has, for 52 years, existed as a social group and fundraising organization for LGBTQ causes. The odd-couple pairing — Bass’ minimal sculptures and canvases alongside the court’s maximal regalia — reveled in the “queering” of traditional symbols and titles, celebrating acts of creative defiance that are at once forms of personal expression and self-preservation.

Best Installation Made Entirely of Foam: 2062

In July, Guerrero Gallery hosted Oakland artist Joey Enos’ gloriously foam-filled solo show, 2062. That title is a reference to the temporal setting of the Jetsons, released by Hanna-Barbera the same year the Flintstones cheerily aired its anachronistic version of the past (1962). Enos’ show paid homage to both while nodding to the false sense of American utopia they projected. The machismo of his monolithic sculptures, purposefully undercut by their material (dense foam and goopy glue), were especially welcome in a year of otherwise-unadulterated machismo.

Best Artist-Made Book About West Marin: Paper Road

Nicole Lavelle’s 450-page tome has been a bedside staple since my copy arrived by mail from Publication Studio San Francisco. Part family history, part research narrative, part local investigation into land use and the people behind those tony West Marin fences, something about Lavelle’s tone and breezy internet sleuthing hooked me from the very beginning. Perhaps best known as the co-coordinator of PLACE TALKS, a lecture series at San Francisco’s Prelinger Library, Lavelle dives into the specific place of West Marin — in lovely prose, archival materials, website screenshots, handwritten notes and graphic design.

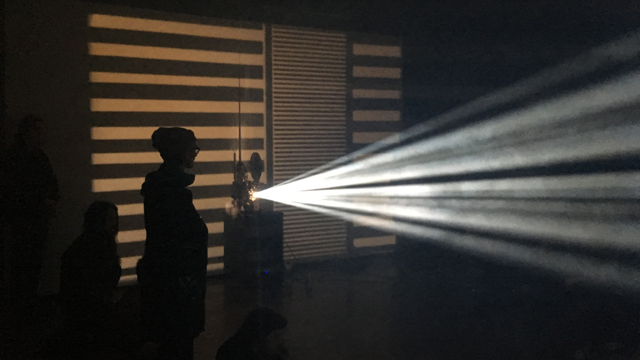

Best Expanded Cinema Event I Almost Didn’t See: Light Music

The culminating event of this year’s Light Field (the second annual exhibition of recent and historical moving image art on celluloid) was very special presentation of Light Music, a late-1970s work by the British film artist Lis Rhodes. By drawing frenetic patterns of black and white stripes across her filmstrips, Rhodes created both image and optical sound. In the Dec. 10 presentation at the Lab, two 16mm projectors beamed onto opposite walls in the hazy room (thanks to two mini fog machines), creating a call and response of visible light. It was exhilarating, like Fantasia but with a pounding, screeching experimental noise soundtrack.

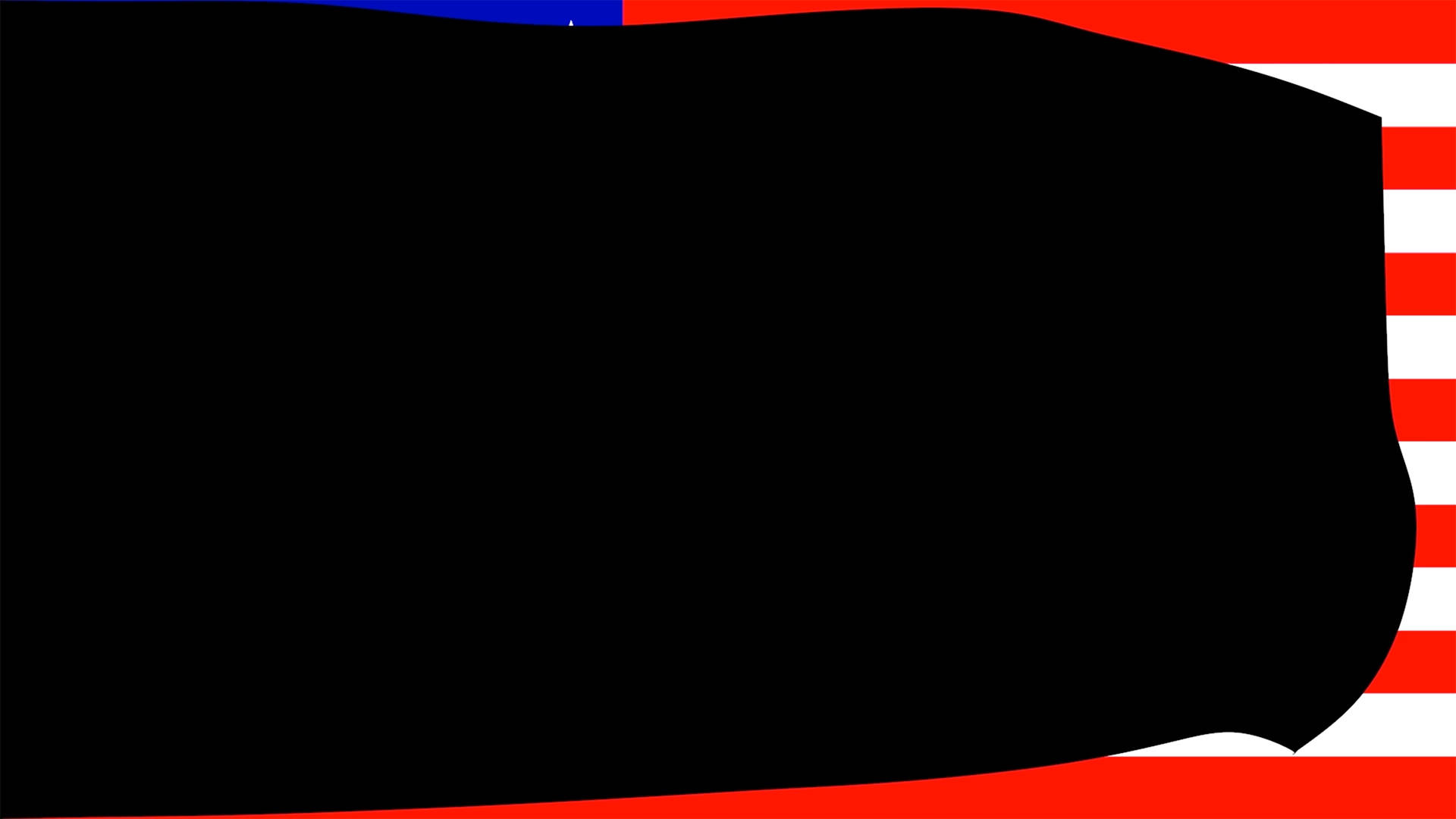

Best Video Art Encapsulation of This Year in the U.S. of A.

On view in May at San Francisco’s CAPITAL, Los Angeles-based David Berezin’s Flag sums up, soundlessly and on endless loop, pretty much all the feelings I have about 2017. The trouble is, I can’t decide if I want the black banner to fly away or completely cover the Stars and Stripes beneath it.