This story is part of American Anthem, a yearlong series on songs that rouse, unite, celebrate and call to action. Find more at NPR.org/Anthem.

The radio version of this story includes conversations with campers and counselors at girls’ rock camps, where “Rebel Girl” has become essential listening. Hear the piece at the audio link.

There’s something contradictory about the very idea of a punk rock anthem. From original snotheads the Sex Pistols to contemporary insurgents Pussy Riot, punk bands kick down norms to make space for new ideas; their music smashes through the rhetoric that often gets people singing choruses en masse. Punk is meant to clear the head, not fill it with sentimental feelings. So it’s notable when a punk song survives its own explosion to become a uniting force for generations beyond its bloody birth. This is the story of “Rebel Girl,” the 1993 song by the feminist punk band Bikini Kill that still echoes through the hearts of girls and women today.

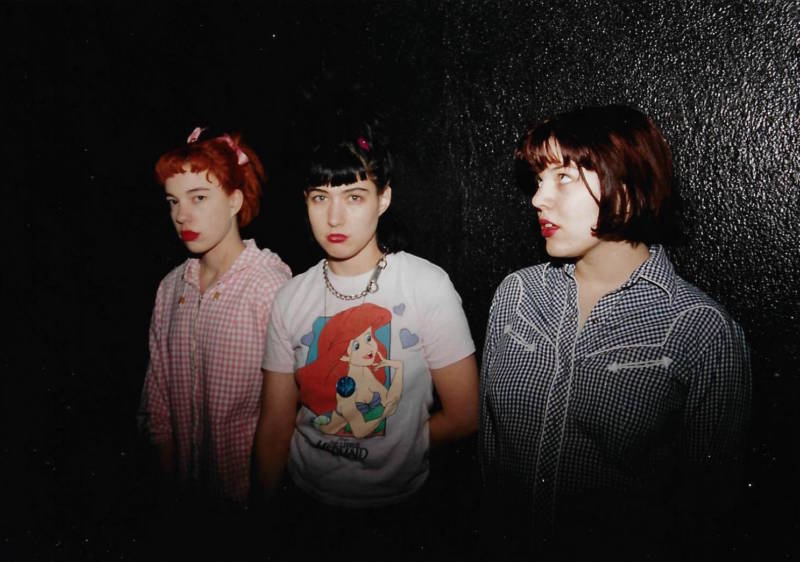

Bikini Kill was the emblematic band in the early-1990s riot grrrl movement, which sought to prove that feminism could become a central element within punk and fundamentally change the music in the process. Hanna, with her alarm bell of a voice and kinetic, funny, sometimes cutting presence, became riot grrrl’s most visible torch-bearer. The band stayed together for seven years, releasing a small discography full of nonstop attacks on sexism and celebrations of independence and self-love. Its breakup in 1997 and the eventual waning of riot grrrl felt to many like the inevitable demise of a dream too brilliant to last.

Twenty-plus years after riot grrrl peaked, however, its influence runs even more strongly through punk and the larger independent music world, and “Rebel Girl” is the song that most often signals its continued relevance. As younger artists from Lucy Dacus to Lizzo carry riot grrrl’s messages forward into the new millennium, even younger girls around the world learn Bikini Kill’s anthem — often as part of the introduction to both music and feminism they receive at rock and roll camp.

Since the first rock camp for girls was founded by women directly inspired by riot grrrl nearly 20 years ago, these summer enclaves have multiplied around the world; the Girls’ Rock Camp Alliance includes members from Buenos Aires to Pittsburgh to Tokyo. Thousands of kids aged 8 to 18 — mostly girls, though a few coed sessions aim to educate boys and welcome non-binary children — form their own bands, write their own songs and encounter riot grrrl’s feminist, anti-racist, LGBTQI-positive principles. And they yell out the inspiring, secretly deep lyrics to “Rebel Girl” in instrument classes and at camp showcases, to instructors and parents who loved it back when and hear it reborn in the voices of the girls they love.

Bikini Kill’s members found other ways to do the work they pursued in that band. Kathleen Hanna founded two influential groups, the electronic-based Le Tigre and pop-punkers The Julie Ruin, finding new ways to explore the intersection of politics and her own subjectivity. She’s proud of riot grrrl’s enduring legacy, especially as it’s flourished at rock camps; in fact, she’s served as a counselor at the Willie Mae Rock Camp in New York.

As part of NPR’s American Anthem series, I spoke with Hanna about the song’s origins and continued resonance. (You can hear the full radio piece, including interviews with girls’ rock campers and counselors, at the audio link on this page.) The story of the song, it turns out, can serve as a pocket history of riot grrrl, a movement that was always as full of love and constructive confusion as it was grounded in revolutionary ideas. Bikini Kill reunited this year for a handful of tour dates in the U.S. and England; “Rebel Girl” became a huge singalong on every date. “It feels great,” Hanna says of singing the song now, to crowds of 5,000 people instead of basements of 10 or 20. “It kind of feels like coming home, but somebody fixed your house up really nice. You know what I mean? Like, we’re not sleeping in the van anymore.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ann Powers: Tell me how the writing of “Rebel Girl” came about. I heard it was inspired by a friend.

Kathleen Hanna: It was inspired by a bunch of friends. Bikini Kill was living in D.C., in this punk house called the Embassy. There was no air conditioning, and we were in the basement just writing songs. Me and Allison Wolfe [of the band Bratmobile] had started doing this group that later became riot grrrl, and it was a bunch of girls talking about starting bands and zines and how we could be feminist in the scene, including doing benefits for other groups that weren’t directly, you know, feminist with a capital “F.” I was also being mentored at the time by the spoken-word artist Juliana Luecking, who has always given me great advice and shown me the ropes as a feminist artist.

All of those girls were totally inspiring me, and the riot grrrl thing was inspiring me, and it was really like I just stuck my hand up in the air and there it was. I don’t really feel like I can take credit for writing it — I feel like it just kind of wrote itself.

I can definitely feel that in how the lyrics shift between various stances. It’s directed at one person narratively, but it is also an embrace that directs itself to anyone it touches. You wrote it as a young adult, but it could be the voice of a young girl — the rhetoric of it, the language of it. Did you feel like you were blending more than one voice in the song?

I mean, that was like my whole shtick in the ’90s. We were all talking about not being binary, not having a single narrator, all that kind of postmodernist stuff. And so of course, I was really influenced by the idea that identity is fluid. [But] it’s also that childhood, sexy feeling of having a crush on someone, where you don’t really understand what’s happening. … I always liked the older, kind of bitchy girls in my neighborhood, who used to leave me out of things. I wanted to be them, or be like them, or make out with them — I didn’t really know. [With “Rebel Girl”] I was kind of like, “All of the above.”

To me, the key line is in the chorus, when you sing: “I think wanna take you home / I wanna try on your clothes.” Because “I want to take you home” is a line that’s in every dude rock song, as a come-on. But then, surprise — I’m going to try on your clothes. Tell me about that line.

We had a thing in Bikini Kill where whoever looked best in an outfit got to keep it. The bad thing about that was, if my suitcase was open, I would come in and find Tobi and Kathi trying on all my clothes. And they looked better in a lot of my clothes than I did! Even if you’d just bought a dress, if someone else put it on and they looked just so great in it, you had to give it to them.