Walking through the galleries hosting the works of this year’s SECA Art awardees, you might find yourself thinking of the future. Displayed across three adjoining galleries on the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s second floor, each artist in their own room, Marlon Mullen, Sahar Khoury and Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle all use old objects as physical starting points. But their final works don’t feel even remotely nostalgic. (A respite from the mood that’s permeating cultural production right now.)

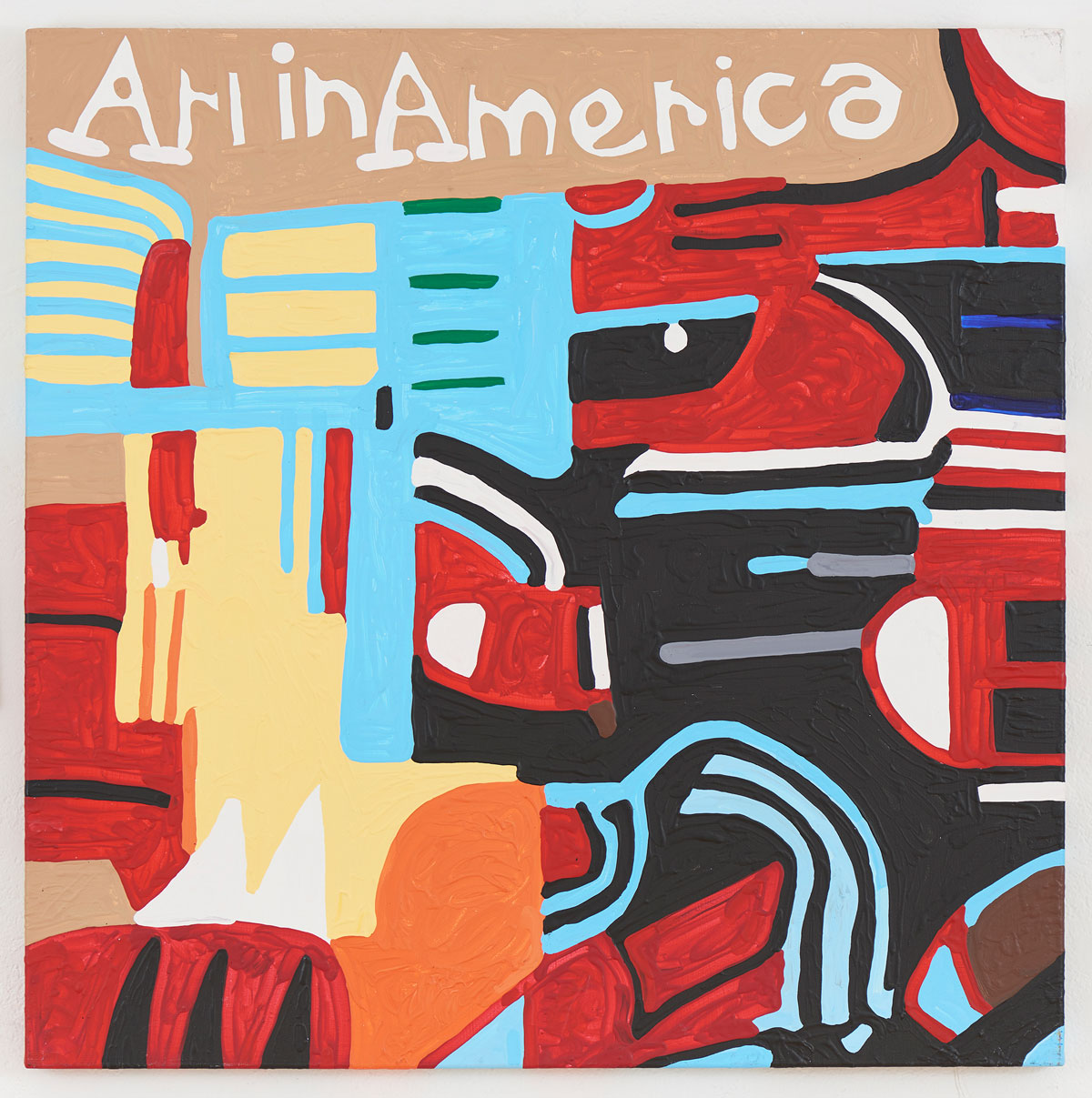

Instead, like me, you might leave wondering if print media will trend towards colors and shapes as vivid as Mullen’s saturated paintings of art magazine covers. If publications followed Mullen’s lead they’d grab our attention instantly. Khoury’s whimsical landscape of ceramics spliced with belts and amphora sculpted from rug scraps and plastic refuse might be a common reality soon. After all, our trash is accumulating at least as fast as the rate of new production. In this near future, maybe we’ll be able to superimpose filters on images that confront the colonial gaze of those images’ authors, the way Hinkle does. Soon, I could summon snakes onto a photograph of a treacherous institution just as Hinkle has layered collage onto an old lithograph of the Lagos Police Court.

The SECA Awards, which brought the three artists together at SFMOMA, are given out approximately every other year to emerging artists in the Bay Area community, culminating in a group exhibition and an accompanying publication featuring essays and conversations on the artist’s works. Selected by co-curators Linde B. Lehtinen, an assistant curator of photography and Nancy Lim, assistant curator of painting and sculpture, all three of this year’s winners hail from the East Bay.

Working out of NIAD (Nurturing Independence through Artistic Development) Art Center’s studios in Richmond, Mullen has maintained an art practice since 1993. Of the three, he is perhaps the least likely to be categorized as “emerging”; his work is in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive and the Portland Art Museum, and he was included in this year’s Whitney Biennial. Since Mullen is mostly non-verbal and autistic, each choice he makes on his canvases is more relevant than statements and press releases about his work. On one canvas, for example, the letter “f” is missing in Mullen’s bright yellow rendition of the book cover for The World of Manet 1832–1883, but the rest of the title is flush and aligned in a pleasing symmetry.

Khoury, who’s based in Oakland, employs found and discarded materials and a sense of humor to create her installations. Her neighborhood of assemblages includes a ceramic shawarma meat on a spit creaking round and round a belted ceramic stand. Some steps away a lonely black stool hosts a spiked heart of gold. Nearby, a bulletproof teller window sits atop a stack of porous milk crates. Some of those crates, along with a few of Khoury’s other sculptures, are draped with smashed pennies strung together like a sequined armor of found luck.