“I know you want me to tear my clothes off so you can look your 50 cents worth,” the cabaret dancer says, scolding her audience from the edge of a stage. “Fifty cents for the privilege of staring at a girl the way your wives won’t let you. What do you suppose we think of you up here? With your silly smirks your mothers would be ashamed of. What’s it for? So’s you can go home when the show’s over and strut before your wives…? I am sure they see through you just like we do.”

It’s a scene so unerringly feminist, it’s hard to believe it was filmed in 1940. Dance, Girl, Dance, a movie that presented dancers as smart and complex at a time when they were more commonly used on screen as little more than background color, was extremely bold. And its landmark scene was par for the course for rebel director Dorothy Arzner.

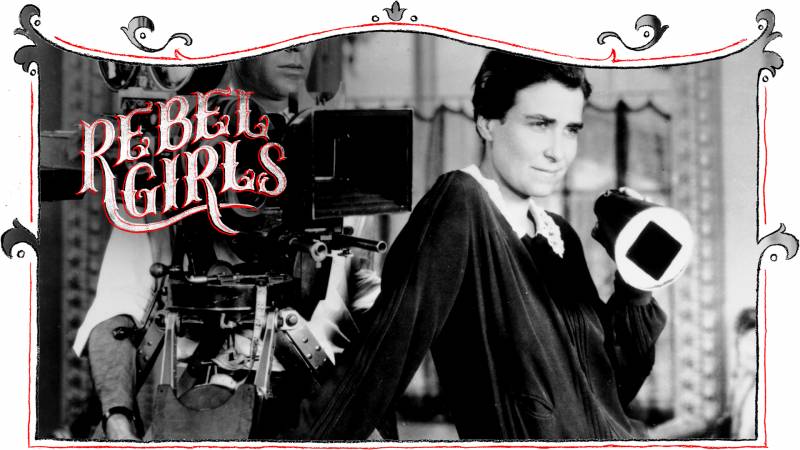

Born in San Francisco in 1897, Arzner spent most of her life in Southern California. What’s clear about the mark she left on the world, however, is that the rebellious spirit of San Francisco stayed with her long after she left. That fearlessness is visible in her film choices, as well as how she conducted her personal life—she was an out and unabashedly butch lesbian at a time when homosexuality was widely condemned.