It’s hard to imagine now, but when Children’s Hospital Oakland first opened in 1914, it was positively ramshackle. Its 38 beds were housed in a decaying old mansion, as well as a small cottage for contagious patients. Its clinic was operated out of a disused donkey stable and its treatment room was in an abandoned harness shed.

Such conditions show how desperately the hospital was needed (it was the first of its kind on the Pacific Coast). But they’re also a testament to the determination of its co-founders, Mabel Weed and Bertha Wright.

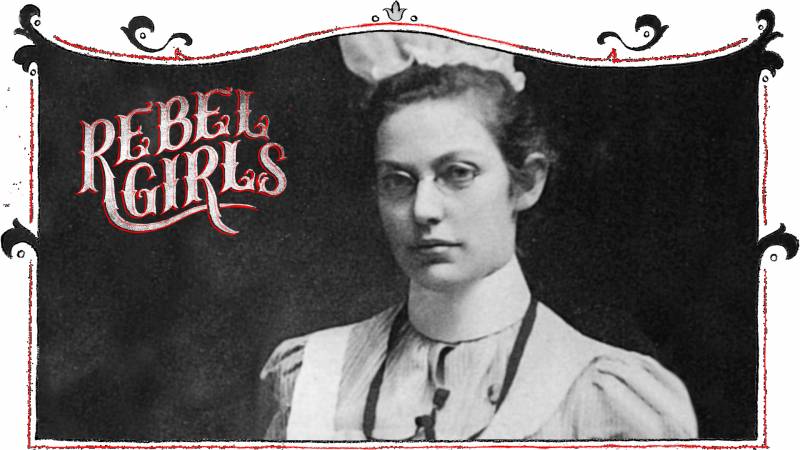

Bertha Wright was a tireless fighter for public health who was accustomed to getting care to the needy by any means necessary. Wright was born in Piedmont, the middle child of three. In 1901, at the age of 25, she graduated from the California Women’s Hospital School of Nursing in San Francisco. She went on to work both there and at the Nurses’ Potrero Settlement House, where she served a large population of struggling immigrants.