At its peak, Black Tumblr was unbeatable. It served a continual dose of contemporary and archival images of black celebrities and strangers alike, an antidote to the mostly white artistic canon that extended on the website.

Photographs of activists and authors circulated with quotes of their work and facts from their lives. Each of Lil’ Kim’s four color-coordinated looks from the “Crush On You” video appeared neatly screenshotted and catalogued. In 2015, Black Tumblr users even organized a #blackoutday, urging their peers to upload selfies and flood the platform with faces of black folks.

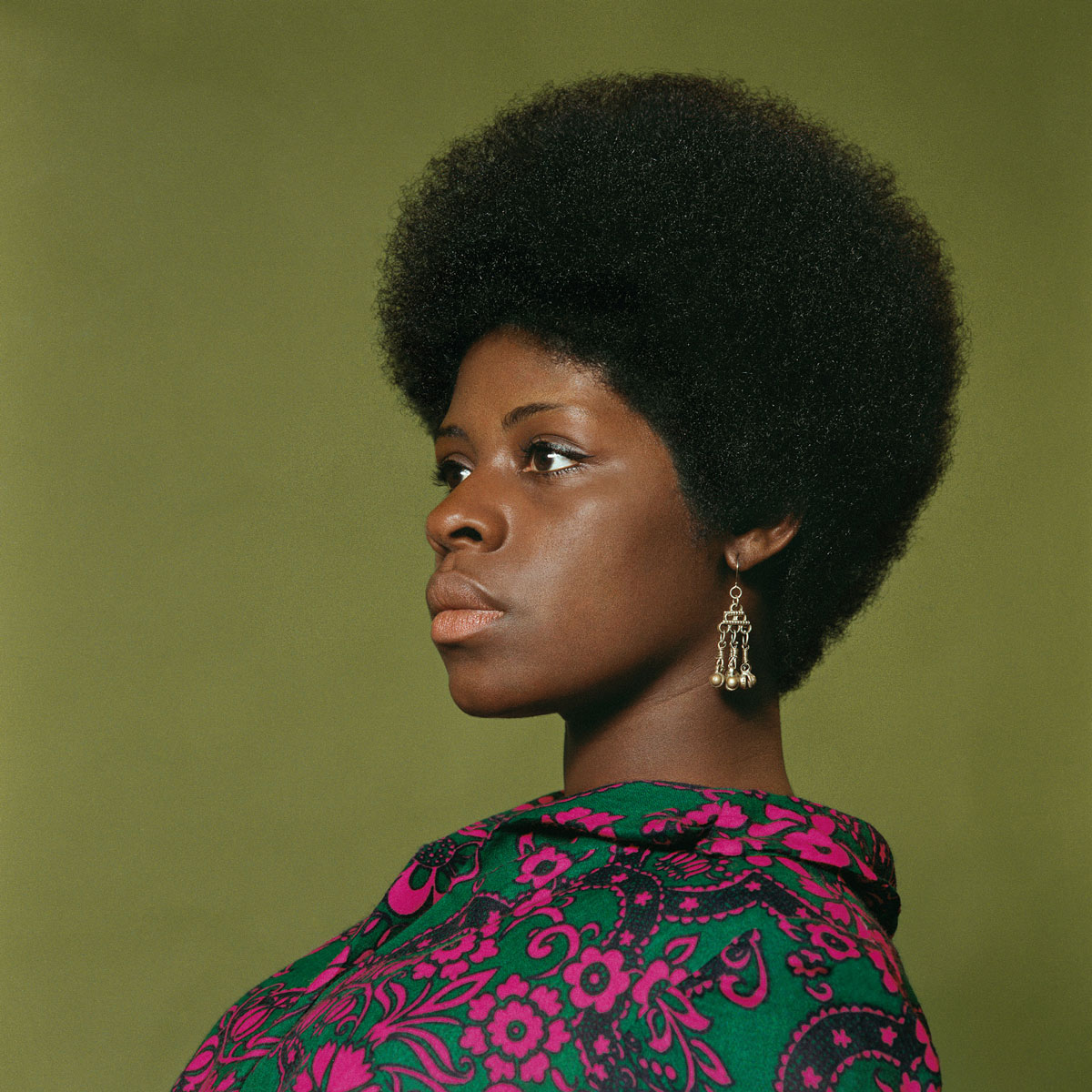

I can clearly recall first coming across Kwame Brathwaite’s photograph of his wife Sikolo Brathwaite between Tumblr’s dark blue borders. That same image, at a much more lavish scale than my computer screen allows, was the first to greet me at the Museum of the African Diaspora’s current exhibit Black is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite. The retrospective, organized by New York’s Aperture Foundation, features photographs, posters and other ephemera from the 81-year-old photographer’s universe in the late 1950s and 60s—a time when black nationalist thought prevailed in cities across the United States.

In that introductory photograph, Sikolo, who was a frequent model for Brathwaite, wears an intricate beaded headpiece, made by designer Carolee Prince, that dangles above her head like a frozen fountain. Against a tan background, her dark brown skin glows. And though she’s looking down, her chin is lifted regally. Hers is a beauty that does what we dream beauty can do: it stuns you, empties your head of other thoughts, and imprints itself in your memory.