On Dec. 9, 1871, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a story about a “specter” that had appeared in the upstairs window of a house on Mason Street. The ghostly face had been scaring neighbors for five days at that point, and as word spread, hundreds of people from all over the city flocked to see it, gridlocking an entire stretch of North Beach.

For One Week in 1871, San Francisco Went Loopy Over ‘Haunted’ Windows

It was children who first noticed the face in the window at 2119 Mason Street. When they pointed it out to the occupant, a Swedish widow named Mrs. Jorgenson, she investigated the room and found nothing out of place. The Chronicle later noted: “The room in which the specter-bearing window stands is small and contains a picture and a looking-glass among the rest of the articles of furniture. Therefore, there is no object which might produce on the window the reflection of a human face.”

As gossip spread throughout North Beach that her dead husband had come home to haunt her, Mrs. Jorgenson was forced to repeatedly point out that the man in the window didn’t even look like him. Which may have been a bit of a shame for her, given that in its front page follow-up report on Dec. 10, the Chronicle described the window ghost as “rather handsome.”

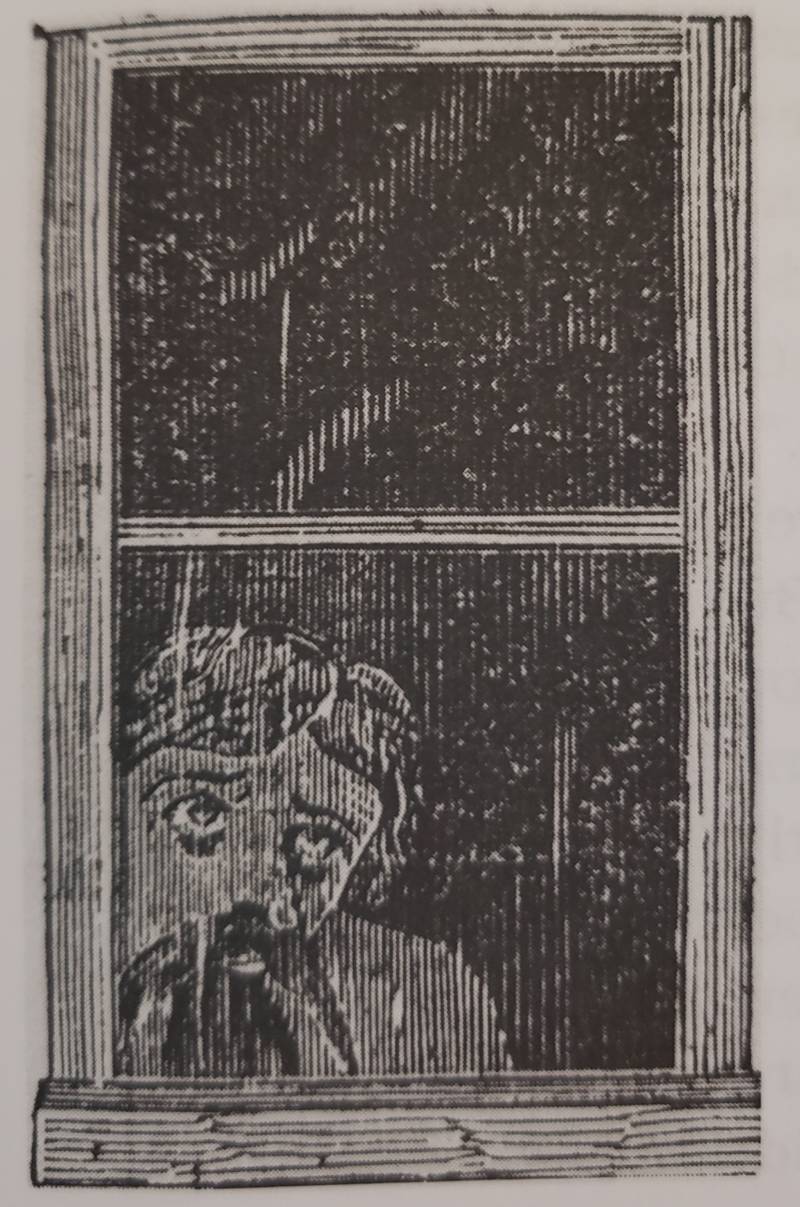

The paper provided both an artist’s rendering of the apparition and a detailed description. “The image is of life-size,” it reported, “with mustache and goatee; well-defined hair parted in the middle, and waving off the forehead.” The paper also said: “The eyes are quite distinct and, from a circular rim beneath each, seem to be spectacled. The head is pensively cast on the left shoulder,” with an expression that appeared “thoughtful and rather sad.”

The same day the Chronicle’s first report came out, the window was purchased for $250 by Robert B. Woodward, the owner of Woodward’s Gardens. “The Gardens,” as it was commonly referred to at the time, was a popular amusement park that was open between 1866 and 1891. It occupied the block bounded by Mission, Duboce, Valencia and 14th Streets, and it squeezed a lot into that space—including a museum, art gallery, zoo, aquarium, botanical gardens and—as of 1871—a haunted window section.

Woodward got the glass in the nick of time—the Superintendent of the North Beach and Mission Railroad arrived later that day in the hopes of also buying it.

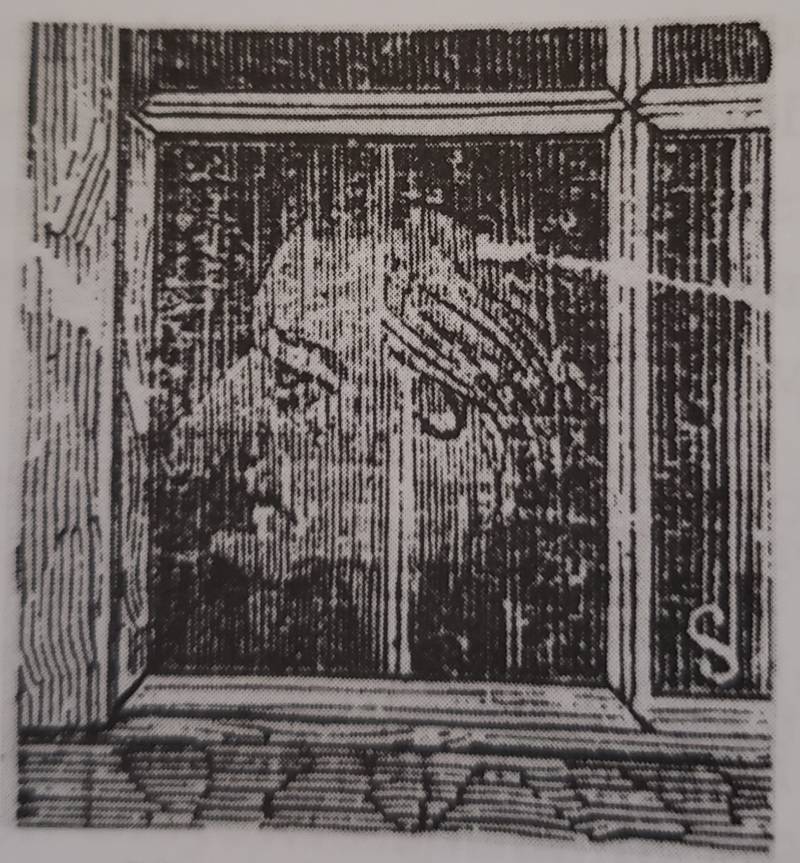

While Woodward was busy removing Mrs. Jorgenson’s window on Mason, half a block away at 708 Lombard Street, another window was causing a furor. And the ghost face in this one, the Chronicle was careful to detail, wasn’t nearly as dashing as the first. “The apparition is of an elderly gentleman with very grotesque features,” it reported. “He presents a profile view, and is looking contemplatively upward. The pane of glass is rather small, and the old gentleman’s head seems to be squeezed in.”

When the homeowner John J. Hucks, noticed the commotion gathering in front of his house, he rushed outside and told them, in no uncertain terms, to scram. “Mr. Hucks was terribly wrothy,” The Chronicle noted. “He asked us of who and what we were and on hearing our business, broke out violently, declaring that he ‘wanted no such damned thing as that put in the Chronicle’ about his house.”

Hucks’ mood probably lifted after Robert B. Woodward arrived later that afternoon and handed over $250 for the window.

By then, attention had shifted to yet another house on Mason Street. Spotted in the window of number 2109 was a—wait for it!—spectral butterfly. Based on his text, this appears to have been the breaking point for the Chronicle reporter. “What the object of any spirit may be in assuming the shape of a butterfly, we can’t see,” he wrote, “unless it is to make a poor reporter overhaul numerous huge volumes of entomology, for the purpose of finding out the particular caterpillar he comes from.”

Shortly after the butterfly image “faded away and gradually disappeared,” the reporter and his sketch artist were informed by a frantic man running up the street “with one boot off” of a fourth ghost window—this one at Mason and Green. “But we had our fill of specters,” the newspaper reported. “It was getting rather monotonous, this ghost business. So we determined not to interview this fourth abomination.”

At the article’s conclusion, it was suggested that the “ghosts” were, in all likelihood, merely “iridescent formations” resulting from a combination of “dust and moisture.” By that stage, it didn’t much matter. Robert B. Woodward was already proudly displaying the “Ghost Sensation!” attraction at his amusement park and the city was filled with enough believers to go and visit it.

In 1893, 14 years after his death, Woodward’s collection of 75,000 curios and objet d’art were auctioned off. Adolph Sutro snapped up a lot of items that would later be displayed at the Sutro Baths—but it’s unclear exactly where the windows ended up. If not for the Chronicle’s willingness to report on such a strange episode, the ghostly windows—and the wacky behavior they inspired—would likely have been lost to the ravages of time. Now they may just live on forever, as all good window ghosts should.