In 1963, when Barbara May Cameron was just 9 years old, she read an article about San Francisco. At the time, Cameron, a Hunkpapa Lakota, lived on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota with her grandparents. As soon as she read about the far-away California city, she confidently informed her grandmother that, one day, she would live there. “And save the world too,” she added.

The Indigenous Activist Who Demanded Inclusion for All LGBTQ+ People

Just over a decade later, Cameron made it to San Francisco and got to work. First, she co-founded Gay American Indians (GAI) alongside her friend Randy Burns. Cameron viewed GAI as both a support group for Native lesbians and gay men, and a means to carve out space for them within the wider (and whiter) LGBTQ+ community. Those pursuits carried over into her writing as well. Though she had originally trained as a photographer at Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts, Cameron found her message was better conveyed through essays. Hers were personal and powerful, and became a loudspeaker for the Indigenous gay community.

Cameron’s 1981 essay “Gee, You Don’t Seem Like An Indian From The Reservation” remains a searing snapshot of the struggle to survive marginalization and thrive despite it. In it, she viscerally describes 26 years of bearing witness to violence against her community. Remarkably, she also uses that backdrop as a means to openly discuss her own lasting trauma and the challenge of erasing color lines.

Because of experiencing racial violence, I sometimes panic when I’m the only non-white in a roomful of whites, even if they are my closest friends; I wonder if I’ll leave the room alive. The seemingly copacetic gay world of San Francisco becomes a mere dream after the panic leaves … I want to scream out my anger and disgust with myself for feeling distrustful of my white friends and I want to banish the society that has fostered those feelings of alienation.

Later, as Cameron describes working on becoming more comfortable in a white-dominated world, she wonders aloud about how she’ll do that without leaving some of her “Indianness” behind. As it turns out, for the rest of her life, Cameron never lost sight of her roots and identity.

Cameron’s ability to use her own life story to magnify the struggles of Native American people was hugely impactful at the time, and remains powerful today. And she did it in essay after essay, never once shying away from uncomfortable, difficult subjects. “It is inappropriate for progressive or liberal white people,” she once wrote, “to expect warriors in brown armor to eradicate racism.”

In 1993’s “Frybread in Berlin” (originally published in the fourth

In The Wind: American Indian Alaska Native Community AIDS Network newsletter), Cameron expressed frustration over the lack of visibility permitted to people of color within the gay community. She wrote:

In reading newspapers in the SF Bay Area, one gets the impression that the only news coming out of the IXth International Conference on AIDS is the disruptions by ACT-UP, pretending they represent the heart and soul of all AIDS activism. But … Alaska Soto from the Native and Indigeous AIDS Network (NIAN) addressed the closing plenary with a reading of the group statement from NIAN. The statement reflected the continued frustration and efforts by Native people to be serious participants in the international arena of HIV and AIDS.

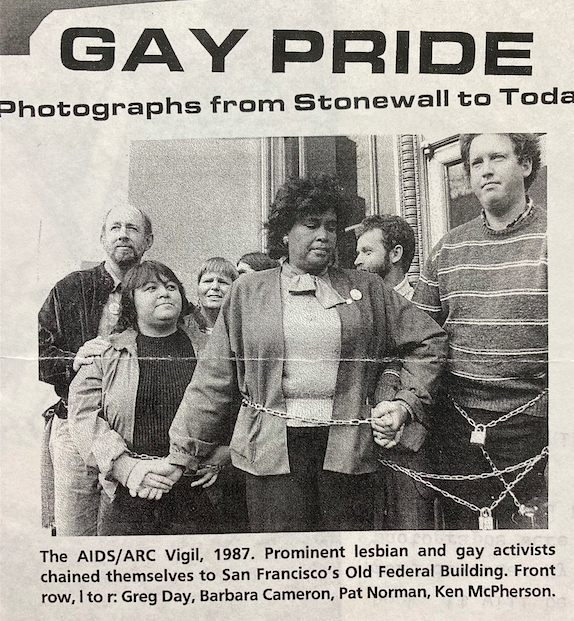

Critical though she was about issues of inclusivity within the LGBTQ+ community, Cameron also never stopped fighting for it. Her activism was prolific. Between 1980–’85, she helped organize the Lesbian Gay Freedom Day Parade and Celebration. (The predecessor to what we’ve been calling the Dyke March since 1993.) And in 1981, she co-chaired the Gay Freedom Day Committee.

Though outspoken and formidable, Cameron is often remembered for her calm and respectful energy in the face of opposition. Those qualities made her a natural leader, and the positions she came to occupy reflect that.

Though outspoken and formidable, Cameron is often remembered for her calm and respectful energy in the face of opposition. Those qualities made her a natural leader, and the positions she came to occupy reflect that.

In the late ’80s, Cameron co-chaired the Lesbian Agenda for Action, an organization that used social and political action to promote lesbian visibility. During the same period, she served as vice president of the Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. The organization’s mission since 1971 has been to advocate within the Democratic party for social and economic justice, and to help elect candidates who are focused on the fight for equality.

Cameron’s position at Alice facilitated new and significant political connections that raised her profile even more. She served as a delegate for Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition at the 1988 Democratic National Convention. Also that year, then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein appointed Cameron to the Citizens Committee on Community Development, and the San Francisco Human Rights Commission. When Frank Jordan became mayor in 1992, he appointed her to the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women. And between ’89 and ’92, Cameron was the executive director of Community United Against Violence—an organization dedicated to helping survivors of domestic violence and hate crimes.

In the end, Barbara Cameron’s passion, resilience and dedication allowed her not only to become a beacon and a voice for marginalized groups in the Bay Area, but also to act as a bridge between them. Chrystos, a Native American poet and activist, once said that Cameron had given her, “a sense of dignity about my place in the world, and my right to be in that place.” Cameron did that for countless Indigenous and LGBTQ+ people like her. Inspired by that, last year, the Pride is a Protest project honored her life with artwork displayed just across from the Ferry Building in San Francisco.

Barbara May Cameron died in 2002 at the age of 47, leaving behind her partner of 21 years, Linda Boyd, and their son Rhys. Despite having spent over half her life in San Francisco, Cameron was buried in South Dakota, just outside the reservation where she was raised. It was a fitting final resting place.

“I rediscovered myself there,” Cameron wrote of a visit to Standing Rock in 1981. “I was sad to leave but recognized that a significant part of myself has never left and never will. And that part is what gives me strength—the strength of my people’s enduring history and contenting belief in the sovereignty of our lives.”

To learn about other Rebel Girls from Bay Area History, visit the Rebel Girls homepage.