Picture, if you will, Mayor London Breed one day emerging from San Francisco City Hall to set fire to half a million dollars’ worth of narcotics piled inside a massive cage constructed out of drug paraphernalia. And imagine if the main thing in that burning structure was opium, which gets you high if you set it on fire and inhale the smoke it produces.

Yeah.

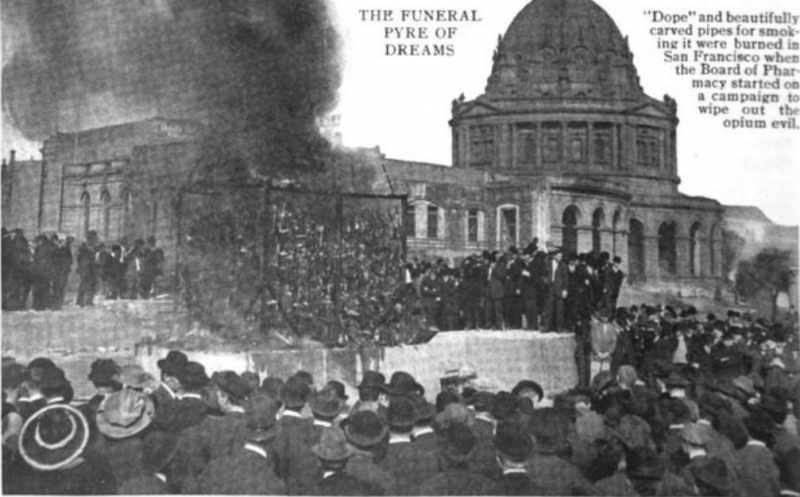

In 1914, this is exactly what San Francisco’s mayor James Rolph did, in front of a gathered crowd of 5,000 people. Rolph’s stated goal was to send a very public message to local drug smugglers and dealers. (That message, to be clear, was supposed to be about zero tolerance, not the dangers of secondhand smoke.)

According to an article from the March 1914 issue of Technical World Magazine, “All the condemned articles were piled upon the stone ruins of the old City Hall. With the tins of drugs were mixed excelsior and other highly inflammable material, while the pipes were hung side by side on scaffolding erected for the purpose.” The photo accompanying the story called the resulting bonfire “The Funeral Pyre of Dreams.”

This drug blaze was the result of an 18-month crackdown by California’s State Board of Pharmacy. During that time, 1,200 people were successfully prosecuted on narcotics-related charges, a multitude of pipes and syringes were seized, and $20,000 (in 1914 money) of opium, morphine and cocaine (around “10,000 packages”) was confiscated.