Cauleen Smith’s work is both Afrofuturistic and deeply historical, deriving inspiration from previous generations of Black women whose activism and art offer a gateway to spiritual enlightenment and liberation. Both poetic and political, Smith’s films weave in and out of real-life utopian universes, and show how these radically generous communities can offer a model for the rest of society.

One of Smith’s films, the 2018 short Sojourner, explores communal settings across California, including Alice Coltrane’s ashram in the Santa Monica hills and Noah Purifoy’s Outdoor Desert Art Museum in Joshua Tree.

Sojourner is currently on display in immersive installations—complete with a shag rug, disco ball, and custom wallpaper—at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (Due to the spread of COVID-19, both museums have been closed for much of the past year.)

Smith joined California Report Magazine host Sasha Khokha from her home in Boyle Heights to discuss her inspiration for Sojourner and how her work responds to this current moment in history. Her answers have been edited for length and clarity.

On the Concept of Utopia

I’ve grown accustomed to having people dismiss utopia as impossible, fantastical, escapist, or a naive notion. But in reality, people make utopias happen all the time. To me, this film [Sojourner] was about looking very pointedly at individuals, groups of people, and their actions that produced utopian ethics and manifestations in the world.

On the Watts Towers, an Unexpected Manifestation of Utopia

Simon Rodia built the Watts Towers over the span of 25 years in the community of Watts. When he started building, Watts was a predominantly African-American neighborhood. He built the towers after work in a strangely collective manner. There are anecdotes about his neighbors saying, ‘It’s fine if you build these towers, but can you just stop working on them past 10 o’clock? Because we all have to get up to work in the morning.’

Now, the Watts Towers function as a kind of artery and cultural currency and leverage. And the fact that Simon Rodia built these towers and then literally gave them away to the community is an act of radical generosity.

On the Watts Towers Influence on ‘Sojourner’

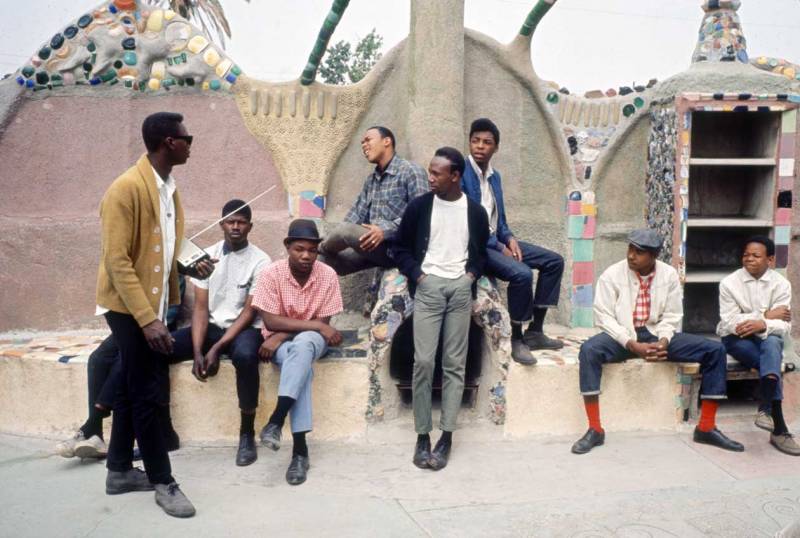

I stumbled on this image by Time-Life photographer Bill Ray while doing research on the Watts Towers. It felt like a fantastical image, of young men holding transistor radios and languidly hanging out in the Watts Towers. Beautiful contrast, beautiful color—almost like a fashion shoot. But as I dug deeper into the context for these photos, I learned that the angle of his story was supposed to be the angry, seething aftermath of the Watts Rebellion in 1965.

One of the things that Bill Ray’s photograph provoked in me was that when we talk about activism, change, politics, and power, the thing that is always pictured is a male image. But in fact, the actual manifestation of change has always been the work of women. I wanted to make it really visible that Black women have been imagining a better world—and not only imagining it, but making it so.

This photo became a talisman in terms of my research. So I decided that I wanted to reenact that photo somehow, but with women instead of the gorgeous young men in the photo he took.

‘We would like to affirm that we find our origins in the historical reality of Afro-American women’s continuous life, and the struggle for survival and liberation. As Angela Davis points out in ‘Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves,’ Black women have always embodied, if only in their physical manifestation, an adversary stance to white male rule. And have actively resisted its inroads upon them and in communities in both dramatic and subtle ways.’ – Combahee River Collective, 1977

On the Combahee River Collective, the Black Lesbian Feminist Organization

Throughout Sojourner you hear voices being transmitted to me, like, right when I needed them somehow. Some are words from the Combahee River Collective, which wrote this astounding statement published in 1977. It discusses the conditions of being a Black woman and it’s still a document of great use and value. It’s very contemporary in terms of the stakes it’s describing.

The part [of the statement] that is so crucial to remember is that if we start building a world based on the position of the least powerful and least empowered in society, we will be building a better world for everyone. The statement is from the perspective of Black women, and their political position actually enables a kind of liberatory ethic for the entire society. I think that is a really important principle and why the document is so vital right now.

On Alice Coltrane, Whose Music Became the Soundtrack for ‘Sojourner’

Sojourner opens with “Om Supreme,” a song where Alice Coltrane repeats the word “California” over and over again in this ecstatic fashion. The song basically says that God told her to move to California.

I have never heard anything like the music she made. She really is bringing in bebop, gospel, and the raga form all into one sound. It just blows my mind. I find it totally intoxicating.

After John Coltrane [Alice Coltrane’s husband] died, she and her four children moved to Calabasas County. She bought this gorgeous piece of land and started an ashram that attracted all kinds of people from all over the country—especially Black people interested in vedic spirituality—to practice religion and music with her.

Alice Coltrane had already passed away when I finally had the opportunity to visit. I was stricken with this world that she’d built and how her students were still there practicing with the same kind of ethic and generosity that she generated there.

On California’s Landscape: Alice Coltrane’s ashram, Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve, Vasquez Rocks, Watts Towers

There’s something about the land in California: those rolling poppies in Southern California, and in particular, the place where Alice Coltrane settled so close to the ocean. In those rolling hills, it feels as if anything is possible.

The main glue of the film is the women carrying neon orange banners through the landscape. They carry them from the Watts Towers to Dockweiler Beach, and all the way out to the desert. The phrases on these banners are a quote, the last four lines of Alice Coltrane’s book A Monument Eternal: “At dawn, sit at the feet of action. At noon, be at the hand of might. At eventide be so big that sky will learn sky.” I just thought that was the most beautiful thing anyone could say to anyone else. It’s like a prayer or a wish, a blessing. A gift.

On the Film’s Closing Scene, at Sunrise in Joshua Tree

I knew sunrises are always gorgeous. That’s a given. But the way that light, once it raked across the desert, the second it crossed over the mountains…wow. It was truly profound. I didn’t have to give a lot of directions. I didn’t have to set a tone. The landscape and that sunrise did everything.

A lot of times people [believe the closing scene includes] 12 Black women in the desert, but it doesn’t. It’s a really diverse group of women. But they are, I believe, practicing Black culture. Those women are holding each other’s hands, grieving together, and walking together. I wanted to simply allow these women to be visible, to be pictured, and to be present in themselves, for themselves.