O

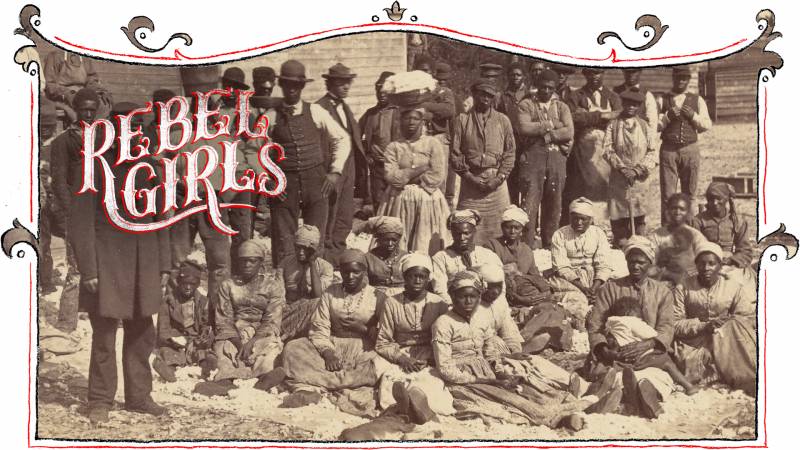

nce Abby Fisher had made a name for herself in 1870s San Francisco, the award-winning Southern chef and businesswoman was bombarded with requests for her recipes. Fisher was more than happy to share over three decades of cookery know-how with her fans. But because Fisher was born enslaved and raised on a South Carolina plantation, she never had access to a formal education; she could neither read nor write.

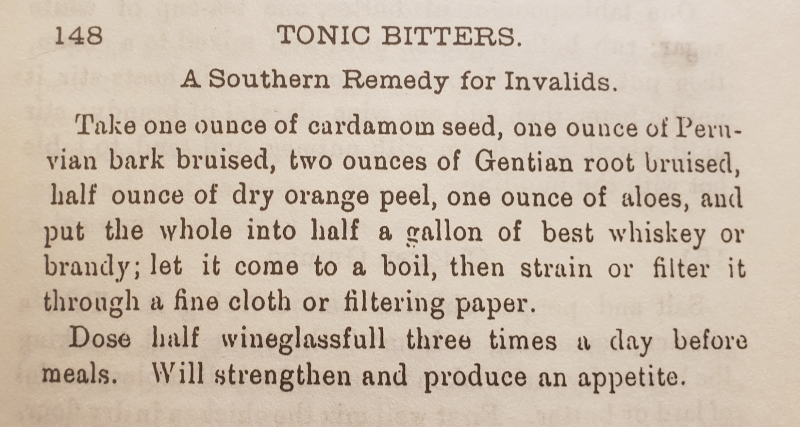

Like all the obstacles Fisher faced in her life, illiteracy wasn’t going to stop her. And in 1880, she became the second Black woman in America to publish a cookbook. (Malinda Russell was the first.) Fisher authored it, rather ingeniously, via dictation to nine friends and associates, all of whom subsequently had their names and addresses printed on the first page of her book. What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking was released in 1881 by the Women’s Co-operative Printing Office, then-headquartered on San Francisco’s Montgomery Street.

Remarkably, Fisher’s book begins with a “Preface and Apology”:

Not being able to read or write myself, and my husband also having been without the advantages of an education … caused me to doubt whether I would be able to present a work that would give perfect satisfaction … The book will be found a complete instructor, so that a child can understand it and learn the art of cooking.

The dictation, however, was not without its flaws. Some of those assisting Fisher in writing and compiling her recipes either struggled with her Southern accent, or simply had never heard of the dishes. (Eight of her assistants were from San Francisco, one was based in Oakland.) As such, there are a few quirks in the text that stand as proof of the difficulty of the task Fisher and her transcribers faced. Succotash is referred to as “Circuit Hash.” Jambalaya is called “Jumberlie.” And mayonnaise is listed as “Milanese Sauce.”

A

bby Fisher was born in Orangeburg, South Carolina in 1831, the daughter of an enslaved woman and a white farmer. On the 1880 census, she reported that her father hailed from France—typical for many landowners in South Carolina at the time. From the moment she was big enough to reach the stove, Fisher worked in the plantation kitchen and became an expert in Southern cooking. She would go on to use those skills for the betterment of her family when they left the South—and slavery—behind.