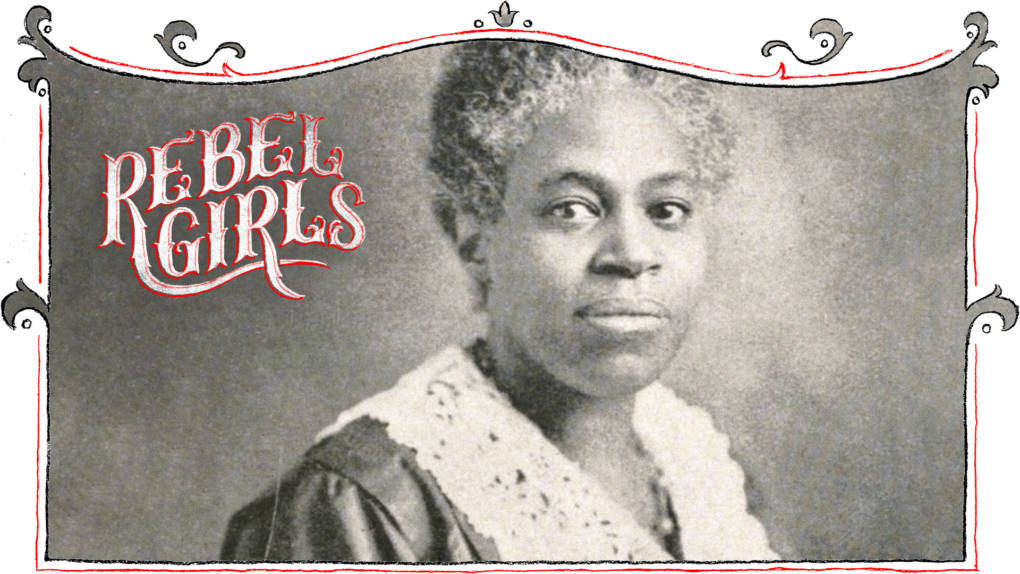

Prior to Alameda County Day, the Civic Center Auxiliary had also taken the lead in a large protest against the conditions in San Quentin for inmates of color. Later it led protests alongside the NAACP against the glorification of the KKK and vilification of Black men in the 1916 movie The Birth of a Nation. But the majority of Simmons’ activist energy was spent on gaining voting rights for women.

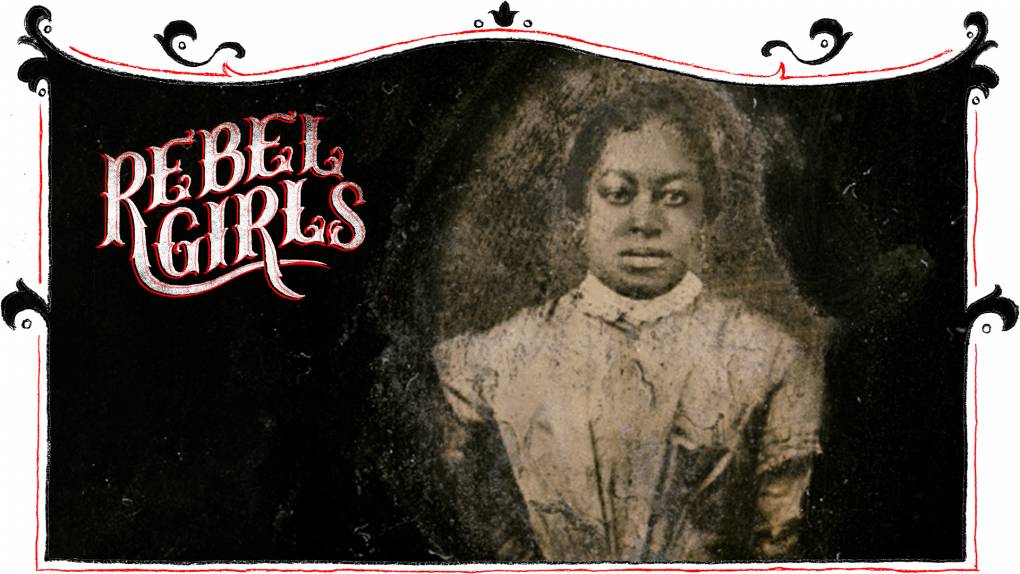

After California women narrowly earned the right to vote in 1911—by a margin of just 3,587 votes—Simmons only worked harder. A Nov. 23, 1911 edition of the San Francisco Call newspaper reported that she was actively educating women about their voting rights and encouraging them to be politically active. She even went on to serve as a precinct captain during the first California election open to women.

The national battle for women’s suffrage, however, was still to be won, and women’s clubs were of vital importance, both socially and politically, in achieving this. Black women’s clubs, like Simmons’ Civic Center Auxiliary, and Oakland’s Fannie Jackson Coppin Club (named after the first Black woman to become a school principal) were focused on both civil and voting rights. Other women’s clubs, like San Francisco’s Votes For Women (led by the Pacific coast’s first female lawyer, Clara Shortridge Foltz) were more singular in their focus. San Jose’s interracial Suffrage Amendment League was one of several examples of women working together across racial boundaries.

The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 was made possible by the dogged work of these women’s organizational and outreach efforts. Simmons herself was such an active campaigner that her name regularly showed up in newspapers around the Bay, as she led high-profile planning meetings with her peers. (On just one page of the March 29, 1915 issue of the Oakland Sunshine, she is mentioned in three separate stories.)