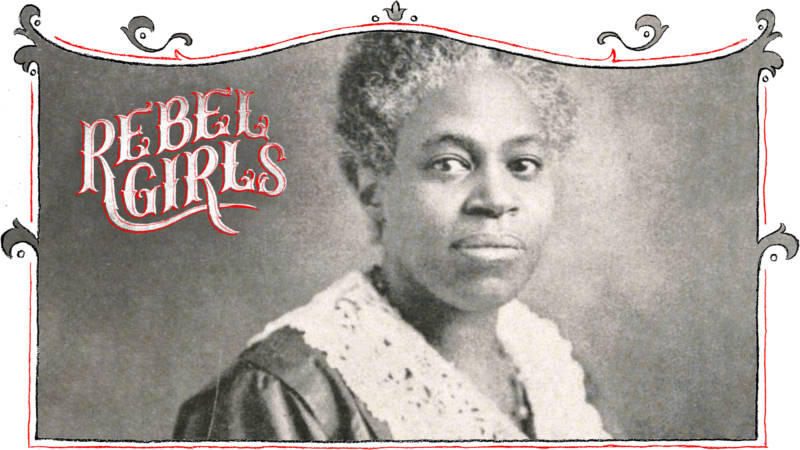

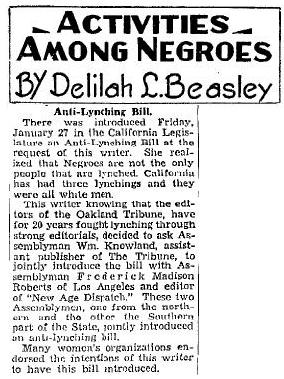

In 1923, The Oakland Tribune started a groundbreaking new weekly column. “Activities Among Negroes” was authored by Delilah L. Beasley, a writer unwilling to waste even an inch of her column space. In her writing, Delilah not only bucked racist stereotypes by putting an emphasis on achievements in the Black community, but also managed to shine a light on the barriers that people of color, and women, faced in their everyday lives.

Even when she was writing about local issues, Delilah’s vision was big picture. She had an instinct and understanding that her column had the potential to act as a direct line to both the white establishment, which could affect legal change, and the average white household, which might encourage a social one. Beasley’s journalistic ambitions started when she was still in her teens and, from the beginning, crossed racial lines. Her earliest work was printed by African American newspaper The Cleveland Gazette and mainstream white publication, The Cincinnati Enquirer.

Born on September 9 in either 1867 or 1871, Delilah’s writing ambitions were temporarily halted in her teens after both of her parents died. After she and her four siblings were separated, Delilah was forced to drop out of school and become a maid for a judge in Cincinnati.

Determined to improve her position in life, Delilah studied hydrotherapy, medical gymnastics and other elements of anatomy until she was able to become a massage therapist. Over the years, Delilah worked in sanitariums and resorts in Illinois, New York and Michigan. For a time, Delilah was known for easing the physical woes of pregnant women via the medium of head massage. She eventually found herself in Northern California in 1910 after becoming a full-time nurse for one of her clients who had moved to Berkeley.

Once in California, Delilah began writing once more, delicately straddling racial divisions in the press. After writing about pro-KKK film Birth of a Nation for The Oakland Tribune in 1915, Delilah was forced to follow it up with a piece in the Oakland Sunshine defending her decision to do so. “News of special interest to us as a people ought to be discussed in our own papers among ourselves,” she wrote. “But, if a bit of news would have a tendency to better our position in the community, then it should not only be published in our own race papers, but in the papers of the other race as well.”