Instead of continually bemoaning that the pandemic is denying me access to physical spaces and the stuff they hold (books, art, films, etc.), I’m trying to think of this period of intangibility as one of research for future consumption. The list of “things to read and see” is growing, but this only makes me more excited for the day when I can start checking things off. The latest (heavily underlined) addition, thanks to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive’s Out of the Vault online series, is the life and work of painter and experimental filmmaker Sara Kathryn Arledge.

Out of the Vault highlights works in the museum’s collection and, as a result, the importance of archival care. Its current offering, a streaming package of six short videos—digitized versions of Arledge’s mesmerizing work, along with an introduction by film curator Kathy Geritz and biographical presentation by Terry Cannon—is one of the most persuasive cases for preserving strange and precarious artwork that I’ve ever heard.

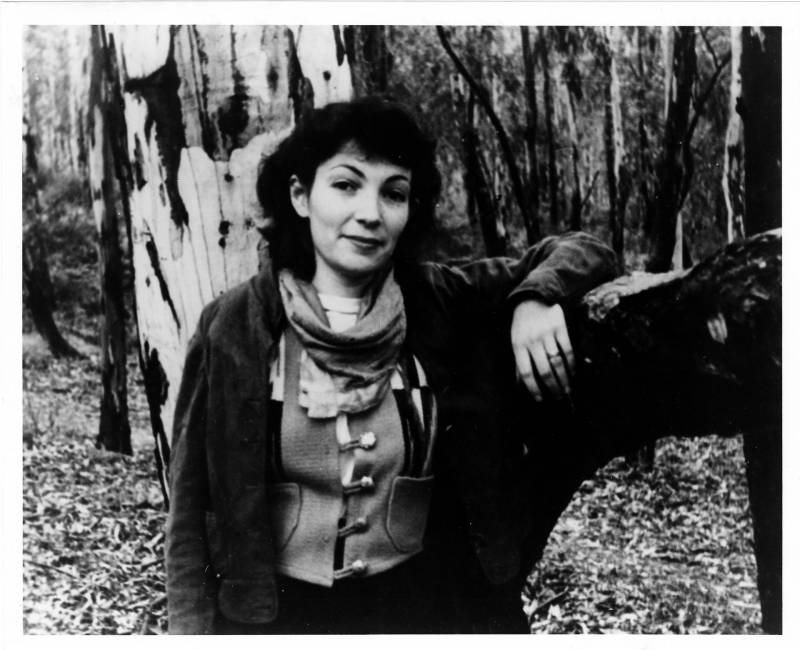

BAMPFA holds Arledge’s films, transparencies and papers thanks to Cannon, who met the artist in 1976 when he was director of Pasadena FilmForum, and who passed away in August 2020. Arledge was in her mid-60s when they met, and while Cannon was thrilled to present her experimental films to new audiences, she was busy with another medium at the time: tiny paintings made on glass slide transparencies to which she melted fragments of colored lighting gels, manipulating the surfaces with toothpicks, Q-tips, napkins and pens.

Cannon describes these small paintings, which Arledge would enlarge by projecting light through them, as having a three-dimensional “undulating sparkle effect” impossible to fully capture in reproduction. And here’s where BAMPFA’s presentation of Arledge’s work whets the palate. One video is a silent slideshow of too many of Arledge’s transparencies to count, the other a “stable” film she made to document her fragile black-and-white transparency work, Interior Garden II (1978). Both induce the feeling of staring up at a night sky and trying to identify constellations; both filled me with an urge to learn as much as I could about Arledge’s enigmatic work.

I won’t spoil the nail-biter of a story Cannon tells of how he came to be in charge of Arledge’s oeuvre. She died in a Santa Cruz care facility in 1998 after living with dementia for many years. Her life story spans the state, with stints in Pasadena and the Bay Area (enjoying the local experimental film community and teaching at California College of Arts and Crafts). And her films still hold power, as evidenced by the ethereal dance-filled piece Introspections (1941–47) and the slyly cryptic What is a Man? (1958).