Her circus life was short-lived, and Rand spent the rest of her teens hustling her way through a variety of jobs—as a nude or swimsuit model, a hat check girl and a cigarette girl. She danced at amusement parks, clubs and ballet companies, and sometimes entered beauty contests—including one put on by the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway. Around that time, Rand was so impoverished, she even spent some time sleeping rough in Central Park.

At 18, Rand found a way to put a roof over her head, dancing with Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds Orchestra—a mostly Black revue on Broadway featuring Cab Calloway and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. This was the show that first took Rand to California and gave her the idea of trying to make it in Hollywood. Once in L.A., Rand found work as an extra, was hired to do a 15-foot dive in a Mack Sennett movie, then got spotted by Cecil B. DeMille, who was the one who gave her the stage name, Sally Rand. He once called her “the most beautiful girl in America.”

Despite her best efforts—in 1927’s Heroes in Blue, Rand performed a stunt that involved jumping from the fourth floor of a burning building—she found herself relegated to bit parts. Throughout her early 20s, Rand was still posing for ads, doing vaudeville performances and, sadly, still sometimes forced to sleep in alleyways. For a time, she danced in a traveling burlesque show called Sweethearts on Parade, and soon she found herself back in Chicago. The clubs where she danced in the windy city were kind to her—in part because she handled gangsters so well. She was friends with Al Capone’s bodyguard, “Machine Gun Jack” McGurn, and palled around with bootleggers on their yachts.

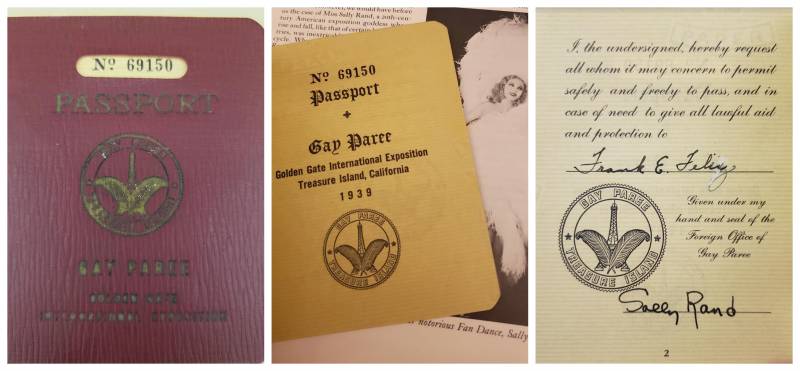

Rand’s World’s Fair success, then, felt both long overdue and hard won. After the fair, things were looking up. She earned $5,000 a week on tour, and was paid $20,000 to appear in 1934’s Bolero. Once more, she wasn’t the star of the movie, but her grace and beauty lit up the screen, and her fan dance was immortalized forever. (The camera panned all the way to the back of the room for her “big reveal” at the end of the routine.)

Rand’s new-found fame made her popular with both men and women. Men were enthralled by her beauty; women were inspired by her devil-may-care attitude, resilience and independent spirit. After Bolero, in addition to touring America with a troupe of roller skating, dancing girls, Rand was also a popular speaker at women’s groups, conventions, luncheons, rotary clubs and colleges. At one point, she spoke at the Junior Chamber of Commerce. At another, she addressed the Class of ’41 at Harvard. Her wise-cracks and sense of humor made her enormously endearing at these events. She once joked, “I’m a girl from the Ozarks who likes going barefooted… up to the chin.”

In 1938, Rand found herself back on the big screen in Sunset Murder Case—this time, with top billing. The movie also served to immortalize her bubble dance, albeit a PG-13 version of it.

Rand never did become a true star in Hollywood, probably because it was while she was performing burlesque that Rand was at her most alluring. She resolutely believed in it as an art form, and as an expression of female empowerment. Not only did Rand continue to perform her classic burlesque routines well into her senior years, she spent much of her life in and out of police stations and courtrooms in defense of it.

R

and was arrested too many times to count, for a litany of offenses related to her onstage nudity. It cost her a fortune in legal costs and fines. At the World’s Fair, because people filed complaints against the fair’s “lewd and lascivious dances and exhibits,” she was arrested repeatedly, and charged with obscenity. At Balaban and Katz’s Chicago Theater, where Rand performed between shows at the World’s Fair, she was arrested four times on her first day alone. Later, one New York judge called Rand’s act “repulsive to public decency,” prompting her to openly weep in court. It was rare for her to show such vulnerability. After one club in Rhode Island banned her, she merely said: “It’s just a shame that there are narrow-minded persons who can’t differentiate between art and indecency.”

In 1933, the San Francisco Examiner reported on an incident in which Rand was confronted by a female police officer before a performance at a movie theater. The officer, Bessie McShane, insisted Rand wear strategically placed gauze on her body. As soon as Rand hit the stage, she ripped the gauze off and used her fans for coverage, as usual. After the performance, chaos broke out as McShane and a male sergeant tried to arrest Rand.

“Arresting a lithe, naked dancer covered in grease paint,” the Examiner reported, “is about as hard as catching a greased pig.” After the police caught up with her, Rand was taken to the station wearing blue silk pajamas, booked for indecent exposure, and released on $400 bail. Rand later accused McShane of breaking one of her toes.