“Poetry teaches you to have radical honesty; politics teaches you how to survive,” says Antonio de Jesús López. “But I never thought I’d be a politician.”

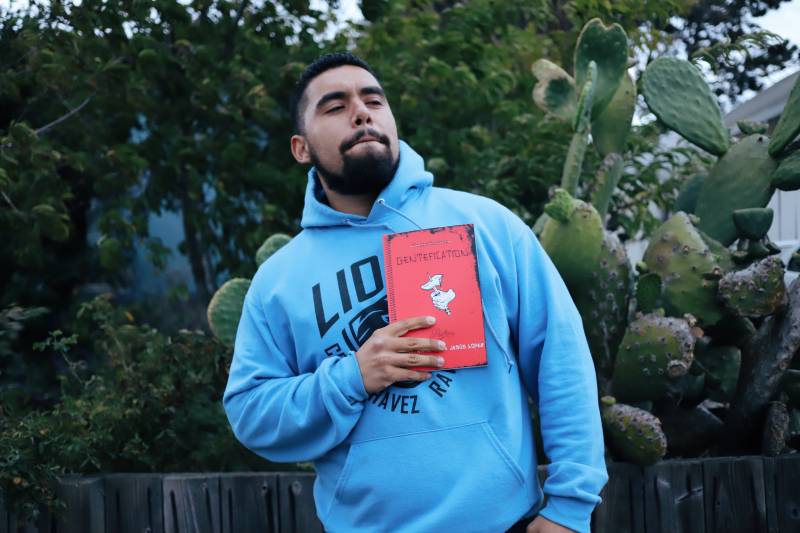

He’s not speaking figuratively: López, whose parents immigrated to the San Francisco Peninsula from Mexico, currently serves as East Palo Alto’s youngest city councilmember, and the second youngest in the city’s history. The 27-year-old also happens to be an ascending poet.

Born and raised in East Palo Alto—a working-class community of less than 30,000 residents that was known as the “Murder Capital of the United States” in the ’90s—Lopez fearlessly explores the relationship between home, safety, faith, injustice, education and, of course, the politics of community in his poems.

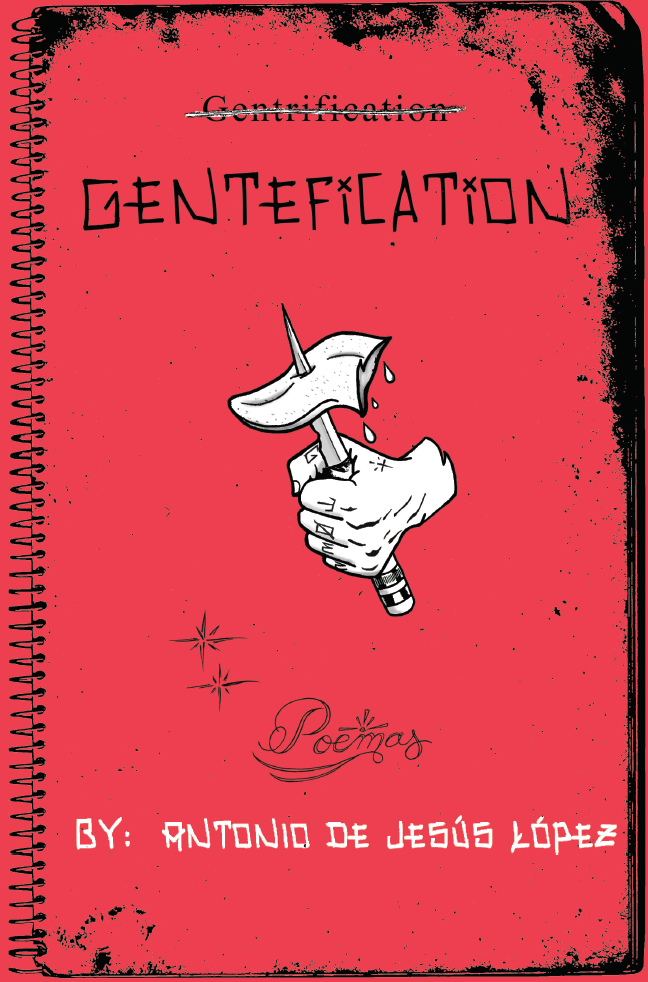

Awarded the 2019 Larry Levis Prize from Four Way Books, López’ 2021 debut poetry collection, Gentefication, takes readers on a journey of the speaker’s social and professional journey while navigating the complicated dynamics of a violently precarious, economically starved and constantly gentrifying environment. (López celebrates the book release with a reading and panel discussion on Sept. 23 at Alley Cat Books moderated by this reporter.)

López is a true factotum: part interior poet, part public servant; part Mexican, part American; part tender, part rugged; part academic, part street. You can feel his multidimensional selves in the alternating frequencies of his work, in which he interchanges tongues from fluent pocho’s Spanglish to professorial historian, and talks in ways that could reach audiences in places as disparate as San Quentin and Stanford.

In both his politics and poetry, López attempts to combine his myriad influences in order to reimagine our modern, fragmented Bay Area. In doing so, he brings attention to the vastly warped landscape of Silicon Valley and those who are trampled by its inequities. He believes Silicon Valley and East Palo Alto can mutually—and ethically—benefit one another.

“There is so much money in the Silicon Valley, how is this happening?” he asks during our interview. “We have a hood right in the middle of it all, and people treat us like just another freeway exit. But if you drive five minutes over, you’re at the Stanford Shopping Center in Palo Alto, with so much white opulence that never looked like us.”

It’s a topic that many Bay Area residents, particularly those with deep roots, have been grappling with for decades. Yet few have attempted to dismantle inequality on such disparate fronts, from East Palo Alto City Hall to the written page.

Modeled after a university syllabus, López’ sequence of poems mimics the idea of being “schooled” on various subjects. He investigates how some of us—namely young people of color—often code switch between multiple worlds, mastering the rules of each one in order to survive. The book simultaneously functions as an academic coursebook, a geographical map, a sociological study, a form of high art and a personal manifesto. At its core, the poet relies on the heart and soul of East Palo Alto to convey a narrative about his own attempt to redefine institutional biases by becoming a part of the institution himself.

Poems like “Course Description” provide a historically lensed look at racial demographics in neighboring zip codes, for example, and feature a literal map of the area’s ethnic composition to illustrate the segregation of his upbringing. “Students will flee the fenced discourses / of gentrification, which cage the conversation to strictly geographic / terms,” he writes. He then leaves the literal map and crosses into the “cultural and psychosomatic Sonoras of English / exile, into a space Chicana feminists coined ‘The Borderlands’,” summoning the legacy of Chicanx resistance from the 1970s as a model for what he considers sacred to his people’s survival.