Here’s a fun game: Browse the digital images of a show, specifically a show of art with an intriguing materials list. The list says, “This art has layers, textures and different finishes.” The images say, “This art is flat.” Fix those images in your memory, in their two-dimensional, pixel-generated state, their scale shrunk by the size of your screen. Then visit them in real life, and thrill to the feeling of complete misunderstanding. Stand in front of something you once thought of as having really no size at all, which now stretches over eight-and-a-half-feet wide. Understand the order of operations, the steps that went into making this surface not a slick, easily reproducible thing, but an object of tangible, visible labor.

Siklon, Didier William’s first solo show at Altman Siegel, draws from the artist’s experience of growing up in Miami after immigrating with his family from Port-au-Prince, Haiti as a child. It is one of those “stand back, take it in, get close, marvel some more” experiences. Accordingly, this is a “you really have to see these in person” plea.

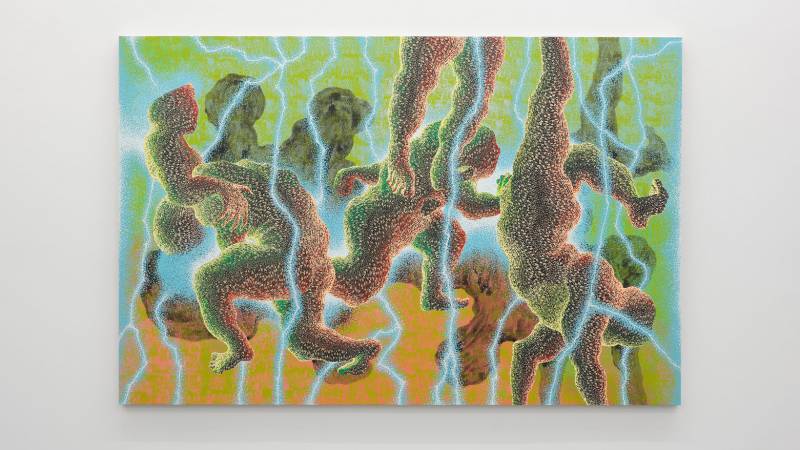

The artist’s paintings involve carved wood, shadowy washes, hand-printed patterns, whiskers of color, and sometimes, additional layers of collage. I’m tempted to describe each layer that (I think) goes into a work on panel, but part of the pleasure of visiting Siklon is puzzling through what at first seems like a relatively straightforward pointilist painting, then resolves into a complex combination of mark-making that creates both a whole image and a system of adjacent and overlapping patterns.

Throughout the show, William’s figures are demarcated from their surroundings by a motif of eyes shallowly carved into each painting’s panel. Eyes curve around heads and legs, arms and hands, morphing to connote the three-dimensional heft of a body. What does it mean to be a body made of eyes? Looking out in every possible direction, William’s figures are both watchful and watched. They take in the details of their environments in a way we can only approximate by peering closely at the artworks that depict them, stepping away and peering closely again.

The exception to this rule is Apprehended Without Incident 5, a smaller work on panel that shows two handcuffed arms, a shadow circling each wrist like a bruise. Here, the eyes form the painting’s background: watching both the police force doing the apprehending and the person being apprehended.