Louise Erdrich’s new novel The Sentence is not your average ghost story. Ghosts are often thought to be malicious phantoms that torment the living, or maybe (if you’re lucky) the spirit of a loved one watching over you. But in The Sentence, which came out earlier this month, Erdrich posits that maybe ghosts are just as human as they were in life—at times greedy, other times sympathetic, but all-in-all, complex.

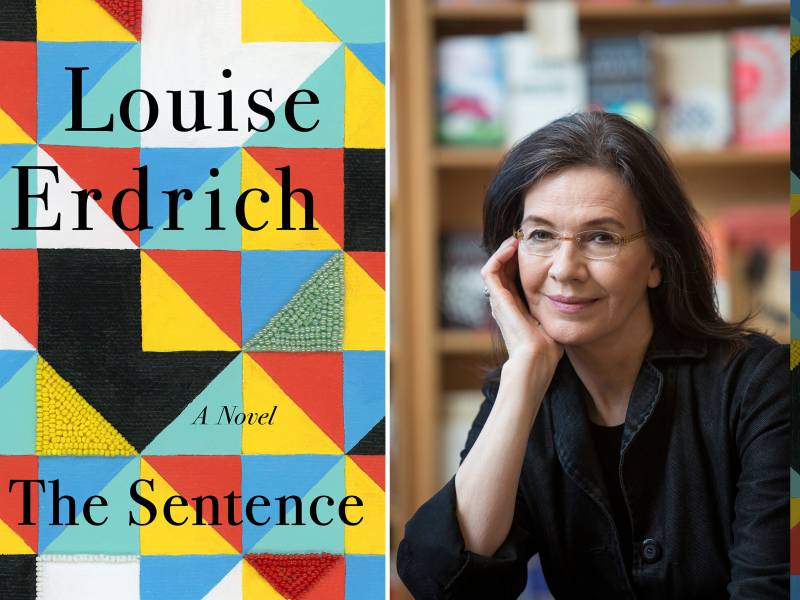

White Ghosts Haunt Native Americans in Louise Erdrich's 'The Sentence'

Flora is all of those things. She’s a ghost that haunts Tookie, the story’s protagonist. In life, Flora was dubbed by the employees at the Minneapolis bookstore where Tookie works as their “most annoying favorite customer.” She’s what Erdrich calls an Indigenophilopath—someone with such a deep fascination with Native Americans that she adopts their identity as her own. Erdrich told me that this inversion of the Indian burial ground trope reflects the realities of American colonialism: “We’re haunted by the spirits of settlers, by the spirits of government officials, by a history that includes extermination policies explicitly aimed at your nation, my nation, all nations. These are white ghosts.”

We spoke about her new novel, why she wanted to turn the horror trope on its head, and why Erdrich herself is a character in her own novel. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The bookstore in The Sentence is haunted by a woman who you describe as their “most annoying customer.” What about her is so annoying to the employees of the store?

This is a bookstore with an emphasis on Native American literature, politics, history, memoir, everything, right? Also jewelry and beautiful baskets, all the things that I wanted to have there in order to make it a focus for people who came to learn more, or for Native people, especially, to find favorite writers. Our most-annoying-favorite-customer comes partly because she loves books, but also because she is an imbiber of all things Indigenous. I mean, she is what people term a wannabe. She’s someone who is not Native, but has a kind of desperation to be Indigenous.

I’ve been thinking about this, and I thought, “What would you call a person who is like this?“ And I came up with a word that has some Latin in it, an Indigenophilopath. Because it includes love, but also a certain pathology. What happens is she decides to find every clue she can to prove her indigeneity, and then operate as though she always was this person. And so that’s the thing that Tookie finds difficult.

In your own words, how would you describe Tookie?

The first word that comes to my mind, and it doesn’t make any sense to me either, is a seraph. I describe her as someone who has landed here in order to toughen up the people around her. Angels can be of varying differences and dimensions, and she’s here as a kind of blazing human being. Someone who has a great sense of the absurd. She cuts through a lot of pain. And she emerges with a sensibility that values what she has in life, which is a comfort. A comfort in her relationship with Pollux, who is her husband, and a love of what gives her the most pleasure in life, and that’s books.

This book takes place from November 2019 to November 2020, which contains so much—the pandemic, the protests after the killing of George Floyd, plus it was an election year. Tell me about writing a book that takes place in the very recent past.

It had to be that Tookie was telling it and that she was the right narrator, for me. She, from the beginning, had this relationship with a tribal cop who arrested her, and that becomes so loaded during this time. So during May 2020, she and her husband have to deal with something that they’ve never uncovered between them.

And that’s what happened, I think, to so many people during that time. It’s like the structures of society were uncovered as though they were covered with sand and the sand blew off in one tremendous month, beginning with those nine minutes.

It wasn’t just that. Obviously, there had been police killings and police beatings happening since the beginning of the state of Minnesota. She and Pollux go back to thinking about the Dakota War and how this incredibly murderous time in Minnesota history is still there, somehow, in the attitudes and in the pain that becomes uncovered in times like this.

Tookie works at a bookstore that’s similar to the one that you own, and she knows you—you’re a character in the book. Could you tell me about setting the book in your world, but not from your perspective?

I didn’t expect to do this exactly the way it happened. Of course, none of us really do. When a writer starts, I think we start writing because we don’t know what’s going to happen. But I wanted to write a ghost story. And I tried to do it in 2014. I wanted to set it in the bookstore because I felt like that’s a kind of haunted space, by definition. It’s a collection of many consciousnesses enclosed in what Tookie calls this “collection of words between cardboard covers.” But it’s really the contents of a person’s consciousness alive or dead. There are many, many thoughts, many dimensions in a bookstore. I thought it was haunted to begin with, and I thought I would really give it an extra haunting by providing a ghost.

It’s sort of an inversion of the Indian burial ground trope. Native people are haunted by a white ghost, as opposed to the way it is often, you know, with white people haunted by Native ghosts. So I’m wondering why you wanted to play off of that kind of plotline?

All of these things, as Tookie says, neatly package white unease with our country’s genocidal and slave-owning and dispossessing origins, right? So, to me, it’s revelatory. It’s something that tells a lot about the consciousness of people who will make the explanation for hauntings, the Indian graveyard trope, right? But in this book, it’s the opposite, because I think that speaks much more clearly to the fact of Native life. We’re haunted by the spirits of settlers, by the spirits of government officials, by a history that includes extermination policies explicitly aimed at your nation, my nation, all nations. These are white ghosts. These are ghosts that have been there from the very first moment a pilgrim fell off the rock and sat down at the Thanksgiving table that wasn’t.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))