“The soundtrack of my life at that point was dominated, in large part, by Wire Train and Translator,” Kopp said, speaking recently from his home in Asheville, North Carolina.

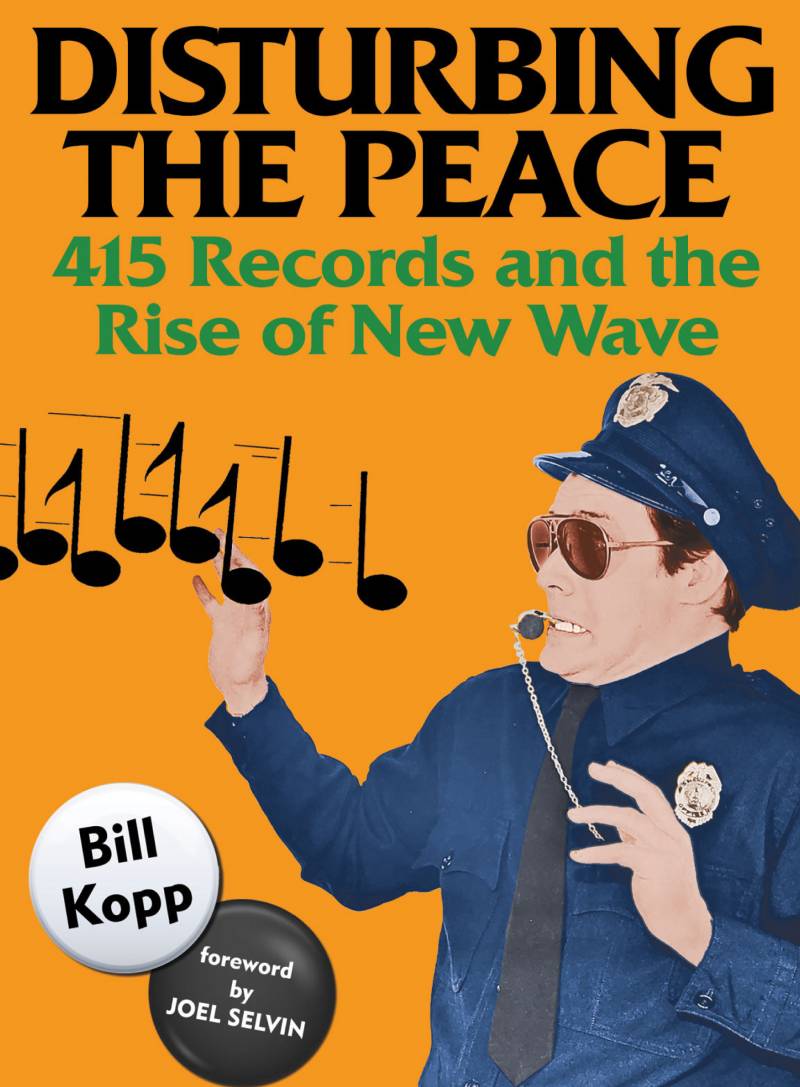

Though he admits he was largely unaware of the other artists 415 worked with, Kopp has since dug deep into the label’s dynamic yet thorny history for his new book Disturbing The Peace: 415 Records and the Rise of New Wave, recently released via HoZac Books.

Meticulously researched and augmented by dozens of photos, ads and other ephemera, the thick volume was built from nearly 100 interviews with everyone involved with the label and members of all the bands that 415 worked with during its short existence, as well as members of the Bay Area scene that the label grew out of.

The story that Kopp presents in Disturbing The Peace shows 415 following the evolution of punk into its more palatable form as new wave. The label’s first release was the provocative single “Decadent Jew” by the scrappy San Francisco band The Nuns (featuring a young Alejandro Escovedo on guitar). It was followed by equally in-your-face 45s by VKTMS, The Mutants and The Offs. By the end, the sound of 415 was far more polished, as evidenced by Until December’s sleek synthpop and the snappy production work by The Cars’ Ric Ocasek on Romeo Void’s breakout single “Never Say Never.”

In between those two eras, some surprising names found their way into 415’s orbit. The label, with the help of Creedence Clearwater Revival member Stu Cook, stitched together an early solo album by Roky Erickson at a time when the former 13th Floor Elevators bandleader had to be checked out of a psychiatric hospital to record his vocal tracks. 415 also released two singles by SVT, a snotty-sounding combo that included former Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Casady.

The only throughline connecting these disparate acts was Klein and Knab’s love for the music. If they liked what they heard, they would throw their full weight behind it with multiple phone calls to record distributors, radio station program directors and journalists. Their desire to support their artists was the sole reason they decided, after many other offers from various entities, to partner with Columbia.

“Howie really felt that he was doing what he could for his bands,” says Kopp, “but they needed tour support in the form of money. They were traveling and sleeping in station wagons. To be able to move beyond that was going to take the muscle only a major label could provide.”

The deal may have helped boost Translator’s undeniably brilliant single “Everywhere That I’m Not” and the New Orleans power pop group Red Rockers, whose second album Good As Gold hit the lower reaches of the Billboard album charts. But it proved to be 415’s undoing.

“There were different people at the label who were more concerned with Barbra Streisand, Bob Dylan and Billy Joel and other Columbia artists that people had heard of,” says Kopp. “‘Do I want to put my time trying to push this latest Translator album or maybe Cyndi Lauper instead?’”

The writing was on the wall for 415 as Columbia refused to release a number of records that Knab and Klein were interested in. All of the bands they had brought to the major label were in the midst of breaking up. The two men sold their stakes in 415 and moved on, with Klein taking a job at Sire Records, home of Talking Heads and Madonna.

Like all great record labels, 415’s stature has only improved in the years since it fizzled out. In addition to Kopp’s book, Liberation Hall, an archival label run by former Rhino Home Video exec Arny Schorr, re-released a chunk of 415’s early catalog in 2020. And the influence of artists like Translator and Romeo Void can be heard in current cool bands like Spoon and LCD Soundsystem.

And the lingering presence of the music, decades after it was first created, is, as Klein explained on the podcast Lost Labels last year, the only acceptable outcome of all of the work he put into 415 Records.