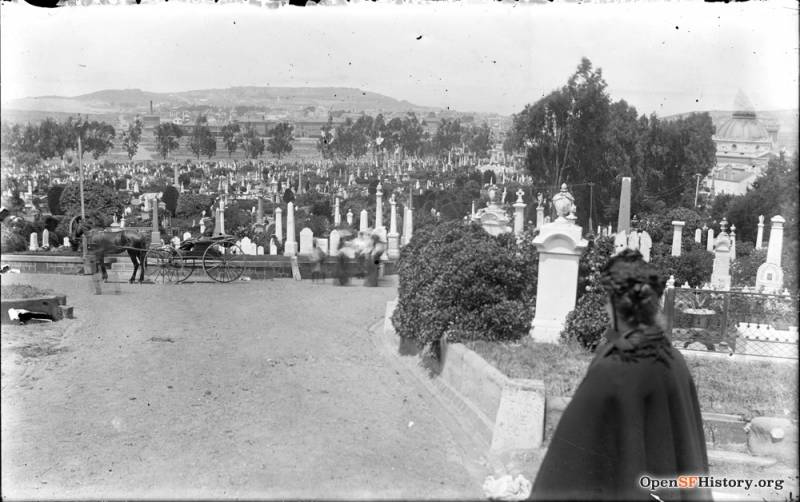

At first glance, San Francisco is strangely devoid of gravestones. It’s been illegal to bury new bodies in the city for over 120 years. And, as most Bay Area residents already know, the city was emptied of the vast majority of its dead back in the 1930s, when bodies were moved en masse to Colma.

Twenty-six thousand occupants of the Odd Fellows Cemetery—today’s Rossi Park and surrounding areas—ended up in Greenlawn Memorial Park, for example. Those bodies are now buried in a part of the Colma cemetery not open to the public.

While almost all of San Francisco’s dead were moved to Colma, many of their headstones and mausoleums remained in the city. That’s because even when relatives of the deceased were successfully contacted, they frequently couldn’t afford to have grave markers moved. (The mass eviction happened during the Great Depression, after all.) The thousands of gravestones left behind were inherited by the Department of Public Works, who started using them in city infrastructure projects.

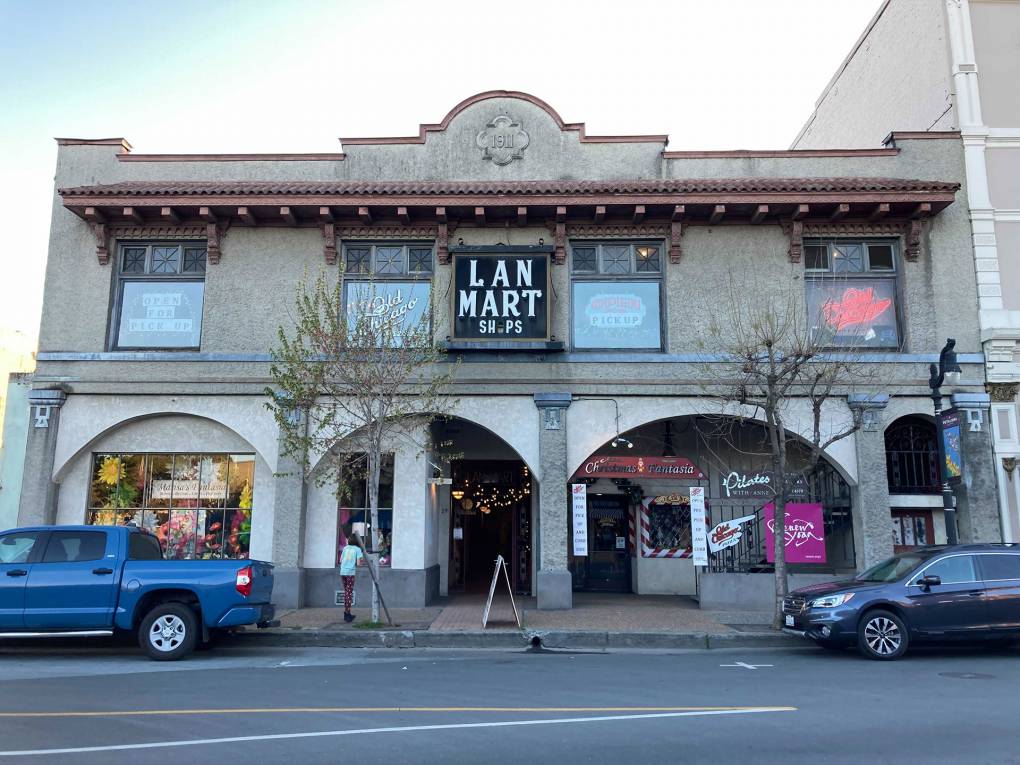

As a result, the north and west sides of San Francisco are still awash with tombstones. They ended up on that side of the city in large part because of where San Francisco’s four largest burial plots were originally located. The Laurel Hill, Masonic, Odd Fellows and Calvary cemeteries once dominated the area around Geary and Masonic. (Laurel Hill Cemetery alone covered 54 acres.)

Here’s where you can still find glimpses of what’s left of the grave markers in our midst.

Ocean Beach / The Great Highway

When the 35,000 bodies in Laurel Hill Cemetery were exhumed and removed, their once distinguished burial monuments were smashed up into more manageable slabs and transported to the beach. Some of the largest pieces were then piled up into fortifying, erosion-reducing diagonal walls along Ocean Beach. Some of the gravestones were also used as bedding in the Great Highway—the road the new walls were intended to protect.