I

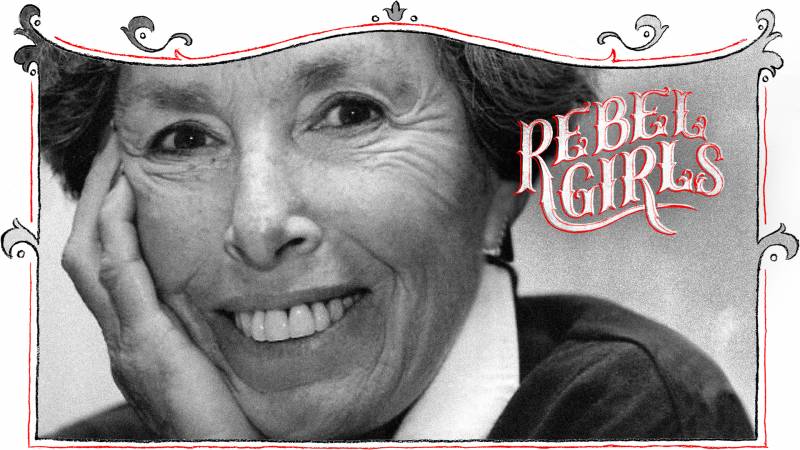

n 1969, Rosalie Ritz’s frank take on Robert F. Kennedy’s assassin was controversial. Ritz, the sketch artist at Sirhan B. Sirhan‘s trial, described him after the fact as “the only honest man” in the courtroom. “It was my first experience with a revolutionary,” she told the Oakland Tribune shortly after the guilty verdict came down. “Of course it was pointless—all killing is pointless. You have to be nutty to do it. But Sirhan knew exactly what he wanted to do and he did it.”

The Sirhan trial was not the only time Ritz came into close contact with a revolutionary. She spent the late-1960s and ’70s covering the trials of Black Panthers including Huey P. Newton, Angela Davis and the Soledad Brothers. She also documented the high profile prosecution of heiress-turned-“urban guerrilla” Patricia Hearst.

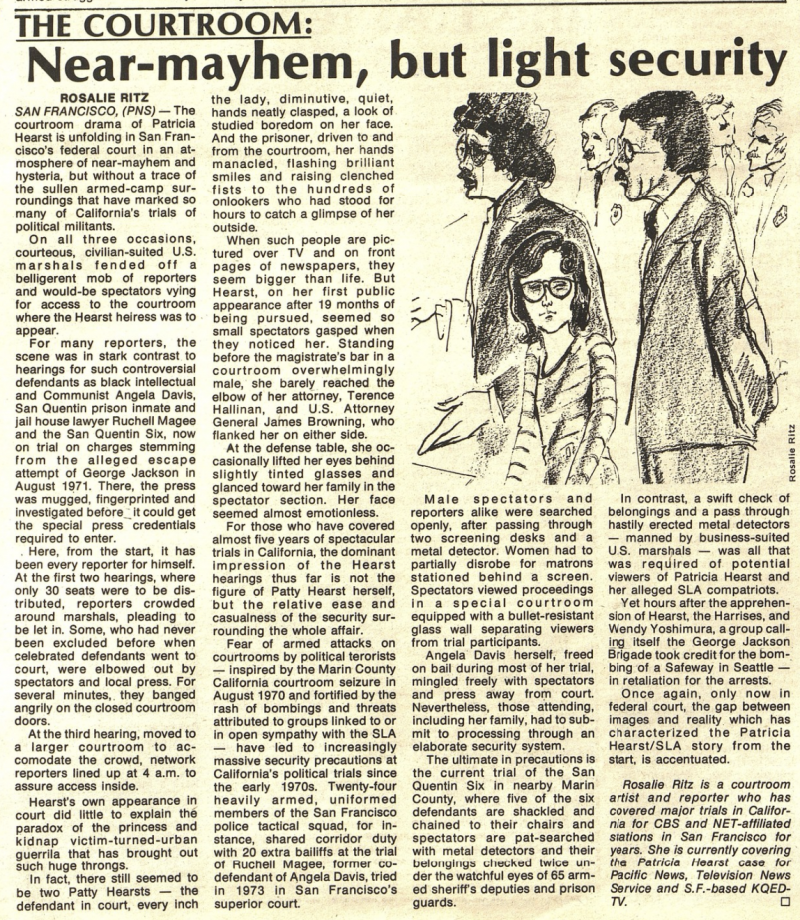

In fact, Ritz was one of the most in-demand courtroom sketch artists of the era, providing illustrations for the Associated Press, CBS News, KPIX, KNXT and, yes, KQED. She was known to make up to 21 drawings a day in court and could sketch an entire jury in minutes. Ritz was also an accomplished writer who took readers behind the scenes. This article she wrote for the Los Angeles Free Press used the Patricia Hearst trial to highlight the overzealous security Ritz had experienced at similarly high profile cases involving Black defendants.

Ritz didn’t just have a front-row seat to one of the most turbulent eras in Bay Area history—she had the talent and determination to share it with the rest of the world. “It’s never as tough as you think it is,” she once said, “if you act from strength, not from fear, and you speak the truth to power.”

That Ritz wasn’t shy about offering her opinions about the events of the day made her work all the more compelling. When Sirhan was sentenced to death, she said, “I am unutterably opposed to the death penalty. It seems vengeful to me. I think anyone who attends a lot of trials would feel very strongly on this point.”