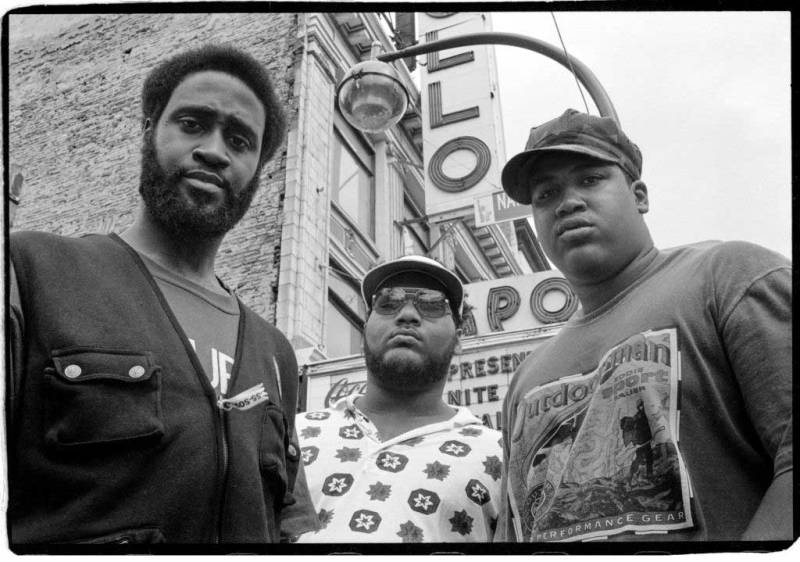

De La Soul’s debut reshaped the public imagination of what hip-hop could be. The core trio — Posdnuos, Trugoy and DJ Pasemaster Mase — assisted by mentor/producer Prince Paul all came straight outta the wilds of suburban Long Island, rapping about advice-spouting crocodiles, Martian transmissions, and an artistic meta-concept they dubbed The D.A.I.S.Y. (Da Inner Soul, Y’all) Age.

De La were part of the Native Tongues, a collective of like-minded artists that included the Jungle Brothers, A Tribe Called Quest and Queen Latifah, among others. Promoting Afrocentric positivity, they purposefully set themselves to contrast against the boisterous brio exemplified by such icons of the era as LL Cool J, NWA or Big Daddy Kane. De La Soul, especially, became smart, sardonic avatars for Black misfits and nerds, mining the sublime from the absurd. On the album, this is partly showcased in their songcraft, especially the humorous skits peppered throughout that turned the format into a rap album staple. There was also the consistently irreverent ways in which Pos and Trugoy adroitly rapped on everything from the garishness of consumer culture (“Take It Off”) to sexy flirtations (“Buddy”) to personal hygiene (“A Little Bit of Soap”).

The group would prove too clever by half, however, at least for the mainstream music media who were quick to dub them “hip-hop hippies.” That encouraged their label, Tommy Boy, to lean further into the aesthetic by creating artwork doused in day-glo colors and cartoon daisies. De La had to refute this characterization in real time; on the album’s big radio hit, “Me, Myself and I,” Pos (aka Plug One) insists, “You say Plug One and Two are hippies / No we’re not / That’s pure plug bull.”

Despite these grumblings, 3 Feet High still brimmed in mirth, including on the musical side, overseen by Prince Paul and including contributions by the entire group. Sample-hungry rap producers had spent the previous few years mining the James Brown and P-Funk catalogs and though De La sampled from both on their debut, they were more likely to create memorable musical moments from children’s television songs (“The Magic Number”), obscure doo-wop singles (“Plug Tunin'”) and classic ’80s pop hits (“Say No Go”). Similar to how their DJ, PA Mase, could expertly splice up a dizzying number of snippets on a song like “Cool Breeze on the Rocks,” the group collectively embraced unfettered sampling as a calling card, a way to demonstrate how drawing upon “found sounds” could create new sounds. Ironically though, their love for sampling is one reason why it took so long for their music to make it to streaming; no one wanted to foot the bill to properly clear all those samples. In fact, the version of the track that appears on streaming is completely reimagined.

Even 30+ years later, 3 Feet High still sounds wondrous and weird, even compared to their later albums, let alone the rest of the hip-hop landscape. Scores of other artists have tried to be clever but few, if any, have embodied a creative impulse as irrepressible and risk-taking. De La’s debut was a proof of concept that the right combination of ingenuity and frivolity could create something indelibly, impossibly hip. (Just don’t call them hippies.)

Time For Heads To Get Flown: De La Soul Is Dead (1991)

Imagine debuting with a gold record, lauded as darlings of “alternative” rap, and then using your follow-up LP to unceremoniously kill off that gilded goose. If the title, De La Soul Is Dead, wasn’t enough of an announcement of intent, the album’s cover removed any lingering ambiguity: a broken pot of daisies, knocked upon its side.

3 Feet High felt like a kaleidoscope of colorful ideas splashed against a wall and the group’s sophomore effort was equally intentional but with a darker palette. Consider this LP’s recurring skits: all meta-level self-deprecation where we overhear a pack of misanthropes listening to the album in real time, trashing the group and its pretensions at every opportunity.

De La also dabbled in heavier social commentary, whether mocking the violent posturing of gangsta rappers (“Afro Connections at the Hi 5”), addressing the trauma of drug addiction (“My Brother’s a Basehead”) or most surprisingly, turning a story about familial sexual abuse (“Millie Pulled a Pistol on Santa”) into a commercial single (and one of the most depressing holiday songs ever).

Yet, De La’s symbolic death and reinvention wasn’t nearly as dramatic as fans might have feared. Though the trio puffed their chests out a bit further and their humor leaned a touch darker, the album still brimmed with a similar exuberance to 3 Feet High. The LP’s lead single, “Ring Ring Ring (Ha Ha Hey),” braided together various threads of the group’s evolving attitude: on the one hand, it was a lamentation on the exhausting nature of stardom, where De La complains about the parade of aspiring acts hounding them with demos in hand. On the other, the song’s playful post-disco groove injected a sonic ebullience that balanced the weary cynicism lining the group’s lyrics.

It seemed as if the success of 3 Feet High gave the group license to go deeper into their artistic bag: more eclectic samples, more risk-taking (and less commercial) song concepts, and just plain more of everything; the CD version had 26 tracks and all but completely filled the standard 74 minute limit. Combine the album’s density with its wild, creative swings and Dead can be a rather disjointed linear listen if you’re simply going end to end. However, a random shuffle will likely land you onto one of the album’s many excellent songs.

That includes their summer-in-the-park party anthem “A Roller Skating Jam Named ‘Saturdays’,” as well as a Stevie Wonder-inspired reflection on relationship rancor, “Talkin’ Bout Hey Love.” Meanwhile, on the humorous tip, “Bitties in the BK Lounge” might be the group’s funniest track. Leave it to De La to elevate a routine fast food encounter into an epic clash of the dozens between a bored cashier and snarky customer.

It’s hard to overstate how creatively sprawling this album was, even within an era where hip-hop artists were experimenting with all kinds of new styles and modes. Especially in a time when hip-hop still felt deep in a fertile, “anything goes” state of imaginative possibility, De La continued to lead the vanguard of artists searching for the cutting edge.

F__ Being Hard, De La Soul Is Complicated: Buhloone Mindstate (1993)

Buhloone Mindstate is arguably the most “concept album-y” title of all of De La’s releases but the joke is that whatever the album’s concept was, the group seemed content to keep it to themselves. It’s as if De La, with its well-established ire towards the recording industry, decided to just forgo any pretense of commercial accessibility in favor of being “just weird, lost in the woods,” according to Pitchfork’s Andrew Nosnitsky, who also lauded Buhloone as “notoriously and proudly inaccessible.”

This may not sound like a selling point but despite feeling crafted like a puzzle box, it’s a pleasantly compact one — just 10 full-length songs — coming after its two behemoth predecessors. With practically no filler on Buhloone besides its assorted, anticipated skits, the album’s hit/miss ratio is as good as the group has ever delivered and it’s no surprise that hardcore De La fans have long insisted it is the most complete work.

There’s a distinctively urgent energy to much of the album, with the group mining their deep trove of jazz, blues, rock and funk samples to power the propulsion on songs like “Eye Patch” and “En Focus,” or the back-half standout, “In The Woods,” featuring Shortie No Mas whose piercing ad-libs dot the LP. Three albums — and one lawsuit — into their career and the group seemed undeterred in repurposing samples that spanned from Michael Jackson hits to forgotten electro singles to classic soul-jazz sides.

As tense as much of the album can be elsewhere, one of the few times where the group winds things down to a more contemplative groove is on the LP standout, “I Am, I Be.” The song features a particularly poignant set of verses by Pos who both opens and closes the track. By this point in the ’90s, he had already established himself as one of hip-hop’s most thoughtful lyricists, and here he pens a brilliant set of philosophical musings on everything from the challenges of parenthood to dissolving friendships to record label servitude:

I am Posdnuos

I be the new generation of slaves

Here to make papes to buy a record exec rakes

The pile of revenue I create

But I guess I don’t get a cut ’cause my rent’s a month late

It’s all done over a haunting, melancholy track featuring no less than seven different samples, most notably an anchoring Lou Rawls loop. The group took such a shine to the song that they recorded an instrumental version for the album as well and invited funk pioneer Maceo Parker to play his saxophone over it.

However frustrated De La may have been with the rap industry, it’s also clear they have tremendous love for the rap community. Comedic hip-hop legend Biz Markie, who De La later hired as a tour DJ, features on the closing track, “Stone Age,” while the single, “Ego Trippin’ [Part Two]” doesn’t just nod to the Ultramagnetics’ 1986 song of the same name, but is filled with easter eggs for their heroes and peers by quoting and re-using famous lines from Pete Rock and CL Smooth (“When I Reminisce Over You”), Big Daddy Kane (“Ain’t No Half Steppin'”) and Run DMC (“Sucker MCs”).

Fans wouldn’t have known it at the time but Buhloone Mindstate also marked an end to a particular era for the group. The maniacal mind of producer Prince Paul had guided each of De La’s first three albums but at some point post-Buhloone, the group decided to amicably break ties with their mentor and take greater creative control over their subsequent releases. By De La’s next album, they were prepared to reintroduce themselves, no longer as youthful rebels but now as hip-hop doyen, intent on defending the culture’s moral center.

No Offense To A Player But They Don’t Play: Stakes Is High (1996)

The three years since Buhloone Mindstate had yielded a sea-change within hip-hop. The rise and dominance of artists like Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Mobb Deep and the Notorious B.I.G. — among many others — eschewed the Afrocentric positivity that De La’s Native Tongues Family had ushered in less than a decade prior, supplanting it with lurid, violent tales of the rich and infamous.

Hip-hop’s culture war had already been brewing across the ’90s, with artists like Masta Ace, Common and De La themselves mocking what they saw as a cynical embrace of gang-banging and drug-slanging posturing. But few albums drew a line in the sand as conspicuous as Stakes Is High. The album’s very title was part of that manifesto, an insistence that nihilism shouldn’t be a form of entertainment. As Trugoy rhymes on the title track, he was “sick of swoll head rappers with their sickening raps / Clappers of gats, making the whole sick world collapse.” Elsewhere, he and Pos poke fun at wannabe gangsters idolizing the mafia — “Why you acting all spicy and sheisty / The only Italians you knew was icees” (“Itsoweezee”) — and empty slogans — “You cry ‘keeping it real’ but you should try keeping it right” (“The Bizness”). Not all their finger-wagging was so direct; after previously decrying R&B as “rhythm and b*******,” De La cook up a crossover parody with the hilariously titled “Baby Baby Baby Baby Ooh Baby” which nails the generic sound of mid-90s hip-hop/R&B songs so well that with slightly less sarcasm salted in, Tommy Boy could have legitimately released this as a radio single.

Along those lines: The overall sonic feel of Stakes Is High is playful and easy-going. Whatever fears fans may have had about the absence of Prince Paul, De La proved more than capable of maintaining without him (with a few assists by the likes of Spearhead X and then-newcomer Jay Dee/J-Dilla). Befitting an album released in early July of 1996, there’s a downright summery vibe to much of Stakes thanks to a prevalence of mid-tempo beats and filtered sampling techniques; alongside OutKast’s ATLiens, De La may have assembled one of the best backyard BBQ soundtracks of that year.

After the relative minimalism of Buhloone Mindstate, Stakes Is High moved back towards super-size, with 17 song-length tracks (though, notably, no more skits). For all their targeted barbs at the rest of the rap world, much of the album is just Trugoy and Posdnuos at their best, mixing clever braggadocio and heartfelt sentiment in their songwriting. It’s a more grounded effort compared to the zany eccentricity of some of their early releases, reflecting the maturity of the group itself. They weren’t a trio of Long Island naifs anymore; they had reached the upper tier of hip-hop’s hierarchy and Stakes Is High demonstrated the seriousness of that stature — but not without its occasional winks and chuckles.

Certified Rhyme Meadows: Art Official Intelligence: Mosaic Thump (2000) & Bionix (2001)

In 1999, De La Soul and their label, Tommy Boy, had announced plans for Art Official Intelligence as three albums, to be released several months apart. In reality, only the first two installments — Mosaic Thump and Bionix — came out, six months apart, marking the first new major set of De La material in four years. Unlike their previous albums, the AOI volumes didn’t have a unifying concept driving them. According to Maseo, the goal behind them was to release, “just some … real good songs, working with a lot of people that we respect in the music industry.” He wasn’t kidding; the two discs featured over 20 guests, equivalent to all the guests on their first four albums combined.

Of all the albums now made available on streaming, the AOI pair were the most conventional-sounding relative to music of the time. While De La would never have embraced the excesses of the shiny suit era in the late ’90s, their AOI output was decidedly more radio-friendly: slower grooves, melodic hooks, love/sex themes, plus a slew of R&B features including Chaka Khan (“All Good?”), Glenn Lewis (“Am I Worth You?”) and Emily “yummy” Bingham (“Special”). The level of craftsmanship was still high but some of their younger, oppositional spirit now seemed replaced by a lighter, feel-good demeanor. De La at middle age (in rap years) seemed like some chill dudes.

Then again, with 35 songs split between the two discs, there was still plenty of material for long-time fans. Songs like “Declaration,” “View” (both on Mosaic Thump) and “Held Down” (Bionix) continued Posdnuos’ 10+ year reign as one of the hip-hop’s most underrated lyricists while singles like “Oooh” and “Thru Ya City” (both on Mosaic Thump) have bouncy club appeal, only on the group’s terms (unlike their first hit from 1989, “Me, Myself and I,” which De La have publicly disavowed at their own shows).

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))