Frisco Foodies is a recurring column in which a San Francisco local shares food memories of growing up in a now rapidly changing city.

T

his holiday season, my teenage son asked for his first pair of classic wheat Timberland boots. Favored by construction workers and rap legends, Timberlands are prized for their lifelong durability and rugged aesthetic. I should know — I’ve had my own pair of wheats on ice for over twenty years. The style of shoe is canon in hip-hop history; when I interviewed the Wu-Tang Clan for The Source in 2007, they mentioned that their performance fee back then, split between the nine original members, was sometimes only enough for a pair of Timbs.

In the early 2000s, when I worked as a retail associate at Timberland’s downtown San Francisco store, I learned that only the classics were resoleable for life, and that they were water-resistant enough to withstand a quick downpour but not a heavy deluge. They were a good investment, I told my son, but please let Mom pick them out. I wanted him to have a lasting pair.

I loved that downtown Timberland job and have fond memories of taking the J-Church train from Mission Terrace over Dolores Park and through the Castro, before it finally dropped me off at Market & Powell. I was convinced it was the most beautiful Muni line in the city, and the holiday season, with the Embarcadero skyline lit up, made the trip even more festive. It was just close enough to Union Square to feel the holiday cheer in the crisp winter air and hear a melancholy Coltrane song from a street performer’s saxophone. The store itself was small enough for me to form lasting relationships there. And the employee discount was good enough to allow me to play Santa during the holidays.

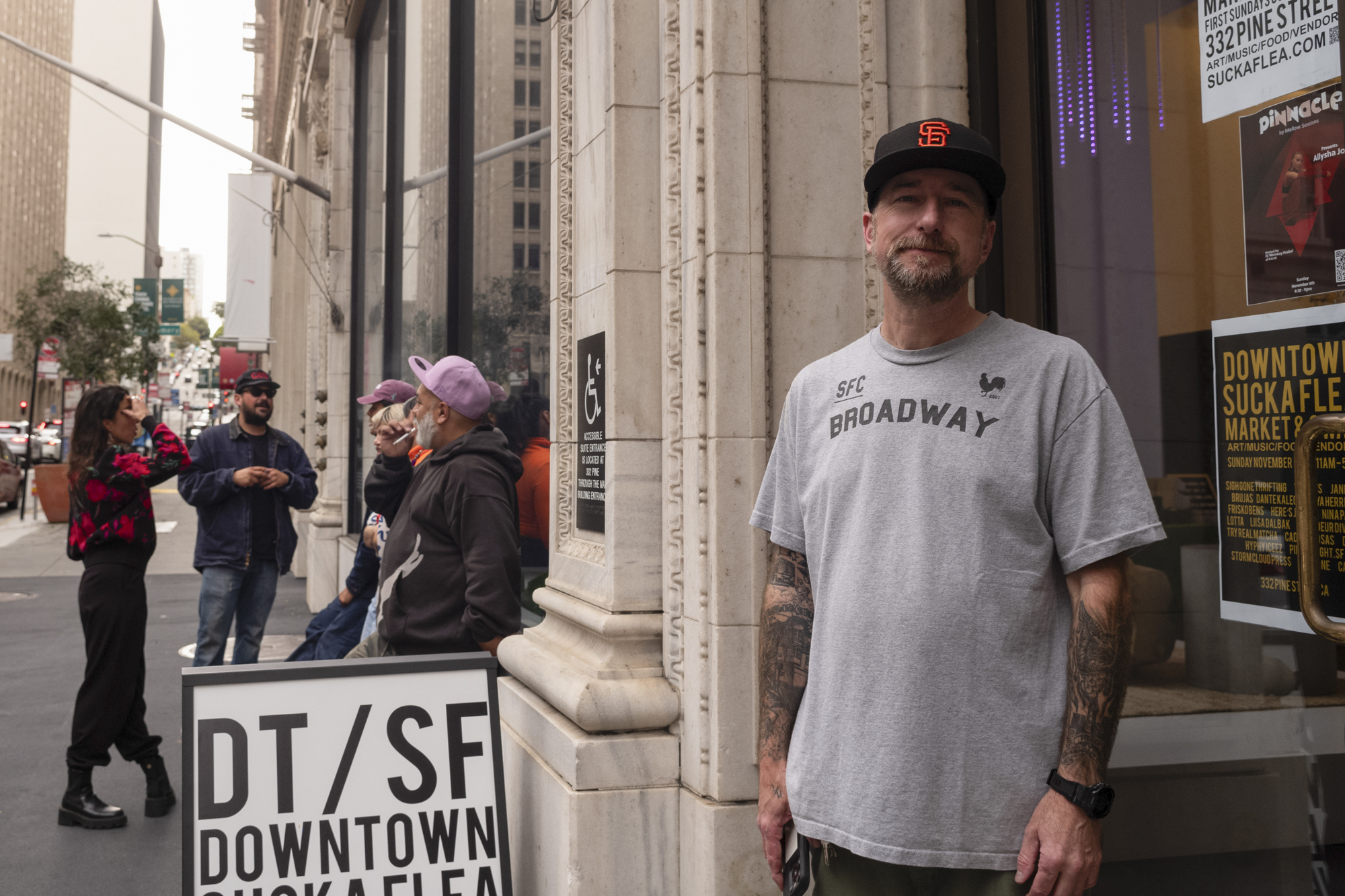

Fast forward to 2023 and I haven’t stepped foot in downtown for years — not since the pandemic accelerated the neighborhood’s retail apocalypse. What used to be the prime destination for Christmas shopping now has to contend with two-day Amazon Prime shipping and a barrage of Fox News reports about the whole area being an open-air drug market. Cop cars park on the corner next to Louis Vuitton, hoping to deter roving gangs of juvenile shoplifters known for their chaotic smash-and-grabs. Even a high-end supermarket couldn’t save its customers from “machete-wielding” assailants and drug users overdosing in the bathroom — though locals might wonder who Whole Foods was trying to cater to downtown in the first place.