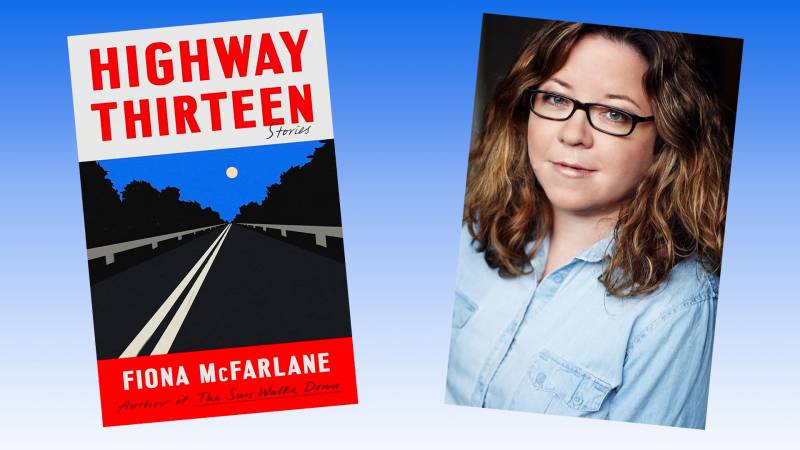

In Fiona McFarlane’s new book, Highway Thirteen (Farrar, Straus and Giroux; $27.00), twelve stories are artfully connected by one serial killer.

The author, who lives in Albany and is currently an Associate Professor of English at UC Berkeley, won the 2017 Dylan Thomas Prize for her first short story collection, The High Places. This second collection is loosely inspired by the real-life serial killer behind the infamous “backpacker murders” that rocked her home country of Australia in the 1990s.

“When those bodies were first discovered and he was tried, the discourse around it was very much, ‘But this is an American thing. What’s happening here? Why do we have an American serial killer right here in Australia?’” McFarlane recalls over Zoom.