When Isis Asare took on the job as the executive director of Aunt Lute Books this year, they were excited to continue the press’s legacy of celebrating often-overlooked authors. Aunt Lute Books, an intersectional feminist press based in San Francisco, published groundbreaking work like Audre Lorde’s 1980 book The Cancer Journals, a feminist analysis of the experience of breast cancer, and Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera, a landmark text on the Chicana experience.

After Small Press Distribution’s Closure, Indie Publishers Band Together

But in March, small presses around the country were left grappling with a sudden and extraordinary blow. Small Press Distribution (SPD), the only nonprofit independent literary distributor in the country, announced that it was closing immediately. Hundreds of presses nationwide needed to rethink how to get books to universities, libraries, bookstores and readers.

“It was definitely a very trial-by-fire transition. I think everybody throughout the indie publishing industry was caught very off guard,” Asare says. “I had a lot of sleepless nights about like, ‘How do we get the word out?’ And, ‘When people place an order, where do they go?’ It was really, really hard. I cannot overstate how difficult it was.”

Now, roughly six months since the closure of SPD, small presses are finding ways to keep going and stay connected. That camaraderie was visible at Litquake’s Book Fair at Yerba Buena Gardens on Saturday, where a contingent of presses formerly distributed by SPD gathered and displayed their wares.

“The dissolution of SPD was rough on a lot of folks, so it’s nice to be able to support people finding their way back after that,” says Sophia Cross, director of operations at Litquake. “The big five publishing houses have millions of dollars available for marketing. The scale of publicity is much, much smaller for a small press. Opportunities like these are really crucial to get in front of people.”

‘A phenomenal blow’

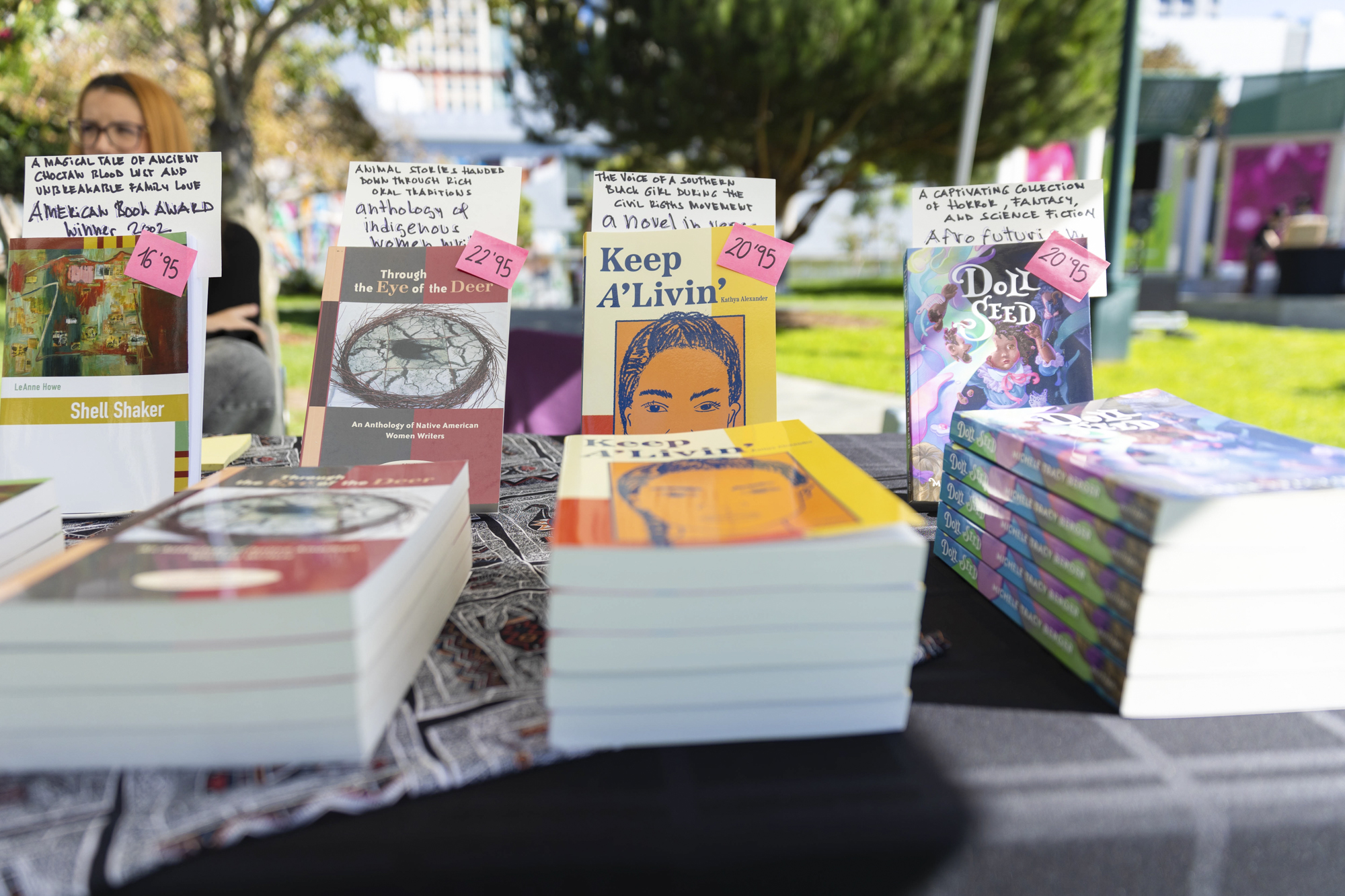

At the Oct. 19 book fair, Aunt Lute Books, Kelsey Street Press, Pelekinesis and Sixteen Rivers Press joined the spread of small presses and literary magazines. Nearby, poets and musicians performed for Litquake Out Loud.

At the Aunt Lute Books stand, the press’ operations director, María Mínguez Arias, stood proudly beside a catalog of treasured books, including new titles like Michele Tracy Berger’s Doll Seed: Stories and Kathya Alexander’s Keep A’Livin’.

The closure of SPD was a “phenomenal blow” that put many presses at the brink of closure, Mínguez Arias says. Aunt Lute Books has since found a new distributor in Consortium Book Sales & Distribution.

“I really like to think that the worst is over,” Mínguez Arias says. “The general challenge is that we have a mission that is not aligned with profit. It’s as simple as that.”

Before SPD shut down, the nonprofit closed its warehouse in Berkeley and raised more than $100,000 through GoFundMe to move tens of thousands of books to warehouses in Tennessee and Michigan. SPD’s closure left small presses scrambling to figure out how to get their inventories of physical books back.

Mark Givens of the Pomona Valley press Pelekinesis could have driven to Berkeley to pick the books up — had he known about SPD’s fate. “But instead they shipped them off to Michigan,” Givens says.

Over the span of more than a decade, Pelekinesis amassed some 4,000 books in the SPD warehouse; it would cost thousands of dollars to ship the books back to California, Givens says.

“After some calculation, a little bit of back and forth, I said, ‘Alright.’ I authorized them to destroy the books,” Givens says. “That was heartbreaking, and it was $40,000 worth of inventory.”

Pelekinesis, now distributed by Ingram, will press on. Givens is looking on the bright side. The small press world is very nimble, he said, and adept at making changes.

Saving the small press community

One organization has been key to stopping small presses from spiraling in the wake of SPD’s collapse: the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP). The New York organization is dedicated to maintaining a vibrant, diverse literary landscape by helping small literary publishers. CLMP just announced a new grant opportunity, the Small Press Future Fund, which offers grants of up to $15,000 to presses once distributed by SPD.

Mary Gannon, CLMP’s executive director, said the organization has fielded hundreds of questions and calls from presses, launched surveys to understand their needs, hosted one-on-one consultations, and more. The group is also collecting data.

Gannon said about half of the active presses distributed by SPD have found new distributors. She estimated 10 presses at most have closed since SPD shut down.

The small press community so far appears to have avoided catastrophe, but the fight to sustain and adapt continues. The CLMP website describes how presses owed money by SPD, or who faced unexpected costs when SPD sent their inventory to a third party without authorization, can take steps to protect their rights, like filing a complaint with the California Attorney General’s Office.

But the situation looks bleak, Gannon notes. According to a July 16, 2024 court filing, SPD has extensive liabilities, including owing over 160 publishers more than $316,500 total. SPD’s cash balance was roughly $73,000 as of April 30, the same filing states.

Gannon says the last few months have been a wake-up call.

Troubleshooting distribution

“Distribution is an aspect of the book business that is frequently talked about as being problematic. Like as a system it is difficult-slash-potentially broken,” Gannon says. “I’m an eternal optimist. The situation, although devastating and horrible, has brought to light some pain points in the system that perhaps we can innovate and address moving forward.”

Back at the Litquake Book Fair, Sixteen Rivers Press is still navigating the new literary landscape. Sixteen Rivers Press, a shared-work, nonprofit poetry collective dedicated to Northern California poets, is taking on the task of distributing their books themselves.

“We’ve got boxes and boxes of books in all of our garages to send books to people who want them. But now it’s a different ballgame,” says Camille Norton, a press member. “Now it’s outreach to bookstores, and of course bookstores are having a hard time.”

Pressing on

Many small presses operate on shoestring budgets, and are run by committed volunteers dedicated to championing writers and poets otherwise ignored by major publishers. Kelsey Street Press has been publishing experimental feminist poetics for 50 years. Carla Hall is honored to represent the press, and show off its storied history.

“I came to the city thinking I could be a poet in San Francisco. That fairy tale dream,” Hall says. “And here I am, supporting an amazing press.”

Kelsey Street Press is now distributed by Asterism Books, a Seattle trade distributor and online bookstore designed, built, and run by independent publishers. Asterism, founded in 2021, has been a lifeline for many publishers after the collapse of SPD. They hovered below 50 presses in February, but Asterism now distributes roughly 160 presses, estimates founder Joshua Rothes.

Despite finding a new distributor, Kelsey Street Press is still taking orders on their website — while also planning book releases, a 50th anniversary event, and an eventual move out of Berkeley.

“We’re burned out. I sometimes think, ‘How do we do it?’” Hall says.

Yet Kelsey Street Press and the others persevere, because they believe in that small press ethos.

“We need to continue to create space for artists that are marginalized, period,” Hall said. “There’s so much hatred out there. There’s just a lot of darkness going on. Fundamentally, if people spent more time with books, and in particular poetry, we would be better off for it.”

The Litquake Festival continues this week, culminating in San Francisco’s Lit Crawl on Saturday, Oct. 26. Click here for a complete schedule events.