In Male-Dominated Pizza Circles, Women Are Grabbing A Bigger Slice Of The Pie

When Laura Meyer won the World Pizza Championship for pan pizza in Parma, Italy, the Italian judges called her the male word for champion. Despite her first-place victory, she was the only winner who didn't get a trophy that day. Hers was mailed a year later.

"They basically refused to acknowledge that a woman had won," she said, recently recalling the snub. She was the first woman to win — and the first American. That was 2013.

The next year, competing as the only woman, she won best non-traditional pizza at the International Pizza Expo in Las Vegas with a triple-infused rosemary dough (rosemary water, rosemary-infused olive oil, and chopped rosemary). And last month, Meyer's simple pepperoni pizza won the first-ever American pizza division of the Caputo Cup, a pizza-making contest in Naples, Italy, the birthplace of modern pizza, and placed third for traditional pizza at a September contest in Atlantic City, N.J.

Meyer is a pizza powerhouse, any way you slice it. But to many in and out of her profession, she's just a woman.

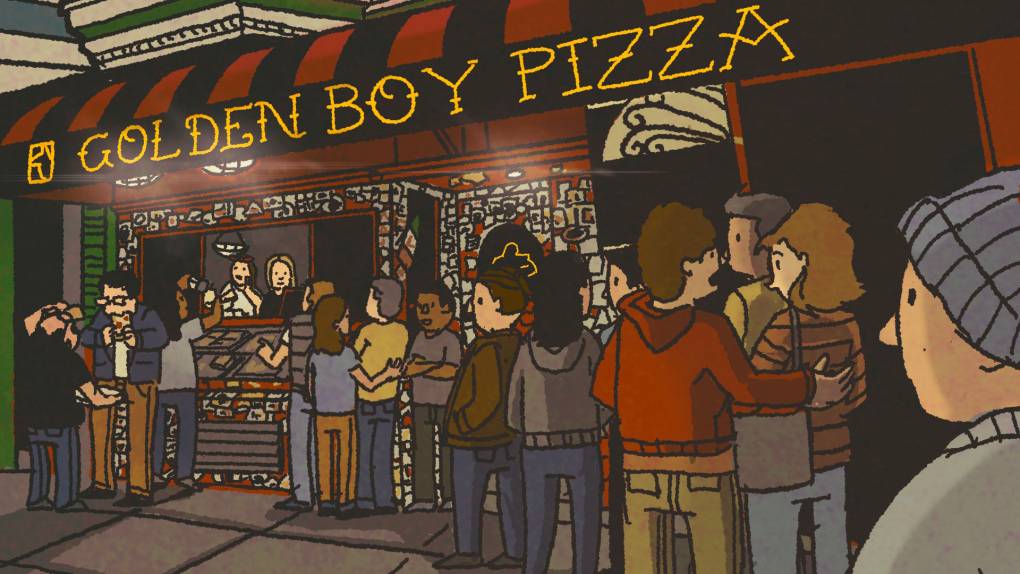

"Women have always been part of pizza, but it's very macho. It has a macho problem, like most of the job world," she said from Tony's, the prestigious pizza parlor in San Francisco where she is owner Tony Gemignani's right hand and runs its International School of Pizza. "Guys stare at my chest. They think I don't see. Guess what? I see. My very first day of work, a coworker just watched me do my job like I was a show, entertainment, an ooh-la-la toy. So many people think I could only be as high up as I am because I'm Tony's wife. I'm not his wife. I'm his talent."

Broadly and frequently, male chauvinism is baked into pizza at every step: from the presumption that pizza delivery people are men to the dearth of female pizza-maker statues. "Pizza making is a profession where men tell you that you belong in a kitchen, but not as a career," said Meyer. "They celebrate grandma slices but not the actual grandmas."

She is trying to change that.

Meyer is a star in a recent surge of prominent female pizzaiole across the country: Sarah Minnick at Lovely's Fifty-Fifty in Portland, Ore.; septuagenarian Norma Knepp in Pennsylvania Amish Country; Nancy Silverton at Osteria Mozza in Los Angeles; Audrey Kelly of Audrey Jane's Pizza Garage in Boulder, Colo.; and this year's best chef in the Midwest, according to the James Beard Foundation: Ann Kim, a pizza maker in Minneapolis.

In New York, where a pizza slice is quintessential to local identity, Nicole Russell serves pickup-only Last Dragon Pizza out of her home in Queens. At the New York Pizza Festival this month, which included pizza makers from Naples and across the U.S., spectators recorded Russell making her tandoori chicken pizza — unofficially the best in show, lifted by a lingering seduction of spices including ginger and mustard oil. One stranger nudged another with a tourist's stage whisper: "She made that! I just saw her do it!"

Later, Russell shrugged. "As a black woman, I'm used to people underestimating me," she said. "But I have a proven customer base and a following. I've had tourists from Texas who came to New York with my pizza on their bucket list. We're not just those women over there. Women aren't just coming up in the pizza game. We're winning up in the pizza game."

With pizza makers finally and firmly having wrestled the national consciousness about pizza away from cheap mega-chains like Domino's, Little Caesars, Papa John's and Pizza Hut, their pies have been released into a renaissance of artisanal styles — bar, cloud, Detroit, Roman, Sicilian — and unorthodox cultural mashups, including Argentine, Korean, Japanese and Swedish. That openness has created a welcoming culture. Yet pizza's association with fast food still impugns it among foodie snobs, to the point that no pizzeria in the United States — or on the planet — has a Michelin star, even though the prize has been given to a $1.50 noodle stall in Singapore, a cheap dim sum chain in Hong Kong, and a crab omelet street food shop in Bangkok.

The off-radar nature of pizza makers has given them stealth potency — if not for seismic change, then at least for visibility. It sounds, well, cheesy, but in Naples the menu at Sorbillo's, arguably the standard bearer of Neapolitan pizza, now offers a special pie — pink ricotta (blended with tomato), mozzarella fior di latte, extra virgin olive oil and fresh basil — in partnership with Barbie, which last year debuted a pizza-making doll. (Gino Sorbillo's young daughter, Ludovica, is an aspiring pizza maker.)

"Women can make progress in pizza that is harder in the macho restaurant world," said Kim, the Minneapolis pizza maker. "I love that because that world can be limiting. It has finite goals of money and awards. I prefer the infinite reach of intention and purpose. The most-popular item on my menu is a Korean barbecue pizza that, for some people, is their first taste of Korean food. It's all the things we say we want food to be."

Pizza-making also doesn't have fine dining's militaristic brigade setup — chef du cuisine, sous chef, saucier, pâtissier, etc. — or its penchant for bullying (and worse); it's far more collaborative and flexible, casual and supportive even at its upper echelons. Though its ethos is often far from feminist, pizza making can be a very feminine craft in the way that it doesn't cling to the rules of a male-dominated kitchen.

When Kelly opened her Colorado pizzeria in 2015, after earning a degree from Le Cordon Bleu, her father urged her to include her name in the title. He and her mother have run a local chain of bagel shops for decades, but they're widely seen as "his." He wanted better for his daughter.

At first, Kelly's kitchen was all men (and her). Now it's 50-50, and some days is all women. "I think of gender equality as craft, as rewarding balance," she said. "We've had men who haven't worked out because they don't want to listen to a woman, which I know because they'd listen if my husband told them the same thing I did."

Now some of these women are banding together — including Kelly, Meyer, and Russell — to make Women In Pizza a movement like Girls Who Code or White Coats Black Doctors. A formal alliance debuted in September: www.womeninpizza.com. And this year the World Pizza Champions, a kind of industry Justice League, increased its female members from 3 to 5 (out of 39 active members).

"Is it lame to say I do it just because it's fun?" said Tara Hattan, who said she is the only female pizza maker in her town of Broken Arrow, Okla. "Girls come just to see me do my pizza acrobatics. I get to be the inspiration or role model or just example I wish I had when I was younger. That's why I bring my ProDough everywhere, out to bars or parties. I want everyone to know women can do this, because they've seen so with their own eyes."

Women in pizza still have frustrations, of course, but flagrant sexism is abating. "Ugh," Meyer groaned in Naples last month, readjusting her trophy for a moment as an Italian television crew scampered over to interview her about her victory. "I'm going to have to wear my hair down."

Richard Morgan, a freelance writer in New York, is the author of Born in Bedlam, a memoir.

Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit NPR.org.