Q: I was astonished by the enormity of the disaster, how little I knew about it, aside from the tangential The Grapes of Wrath. I even asked my parents, who had grown up in the 30s, my mother in even in the Midwest, what they remembered, and they didn't know much about it. Why did it recede so quickly?

A: Almost everything in American history recedes after the passage of time, and things fall out of fashion. George Washington in the 19th century! School kids could recite his speeches by heart, and it was important to know where he had spent the night. Now that's a joke, and we know very little about him generally. So if George Washington, the most important person in setting our country in motion, could be lost, than any subject could be lost.

Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath is about tenant farmers from eastern Oklahoma, who have to leave because of the collapse of the cotton crop caused by the Depression and the drought, while our film focuses on the landowners of the Dust Bowl. The Dust Bowl was called “No Man’s Land” originally because it was quite correctly understood to be not a place for human habitation and certainly not human agriculture. While our film travels to California, where most of The Grapes of Wrath takes place, to look at the Okies, the diaspora, the “exodusters” as they were called in California, [it’s important to remember] that more than 75% [of the population] stayed in the concentrated area of the panhandle of Oklahoma and nearby parts of Texas, New Mexico, Colorado and Kansas -- the parts of the five-state area that made up “No Man’s Land” and the heart of the Dust Bowl.

Even though during the 1930s, 46 of the 48 states were suffering some kind of drought, I think that for most other people, those memories become like PTSD. They just get locked away, and we tend to forget. Generations don't ask about them. But everybody experienced the dust storms because they went all the way east and deposited dirt on Franklin Roosevelt's desk and covered ships out at sea in the Atlantic. That got everybody's attention. It wasn't just one storm or two storms or even a dozen storms, it was hundreds of storms over ten years that were killers. Some were a mile and a half high and a hundred and fifty, 200 miles wide. “A big mountain range,” the writer Tim Egan says in our film, “moving toward you."

Q: But do you think there's something particular to American culture though that turns its back on these stories?

A: I think it's probably partly American culture in so far that we are still a relatively new nation. We tend to burn our history behind us, like rocket fuel, as if we're always going forward, and that's not always the best thing. As we get older, though, we begin to understand the centrality of history to understanding not only where we were but where we are. The past is gone, we will never get it back, but history is the set of questions that we in the present ask the past. It is informed, however unconsciously or subconsciously, by our own wishes and fears and desires and hopes. So very strangely, history very quickly becomes about our future. We use history to give us guides, examples of leadership and heroism and perseverance, but also these incredible stories that remind us how very much like then was to now, and how very much like now is to then. And that is a hugely important and liberating thing. We can arm ourselves with the tools we'll need to take care of these problems.

Q: Have you always been a serious reader of history?

A: Oh, I've read history all my life, and not seriously, just for fun. I never knew that I'd be involved in history. I've wanted to be a filmmaker since I was 12 years old, but I had the greatest harmonic convergence in college where the interest in film intersected with an interest in documentary and then an interest in history and it all came together. I've been so fortunate to passionately know what I've wanted to do now for 37 years and have done it. Making films exclusively on American history and exclusively for public television, I consider myself extraordinarily lucky. I feel like I have the best job in the country.

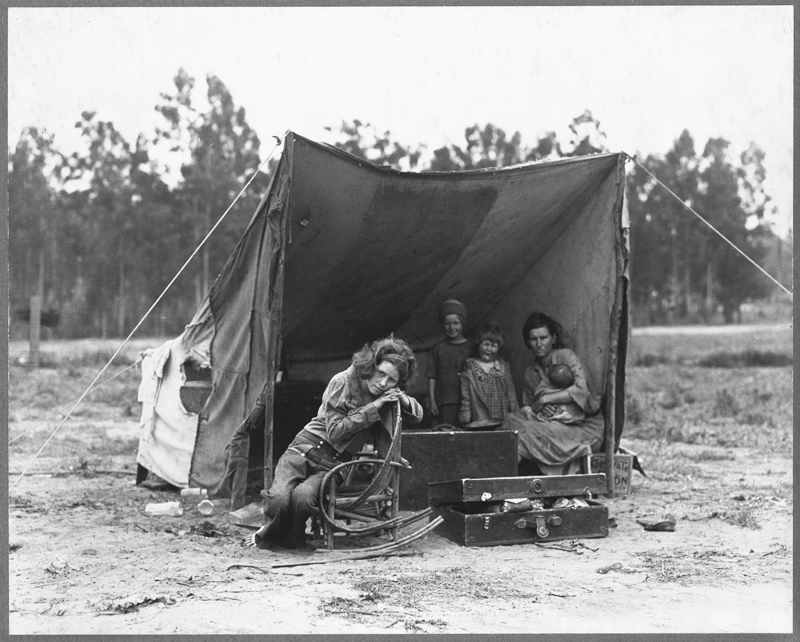

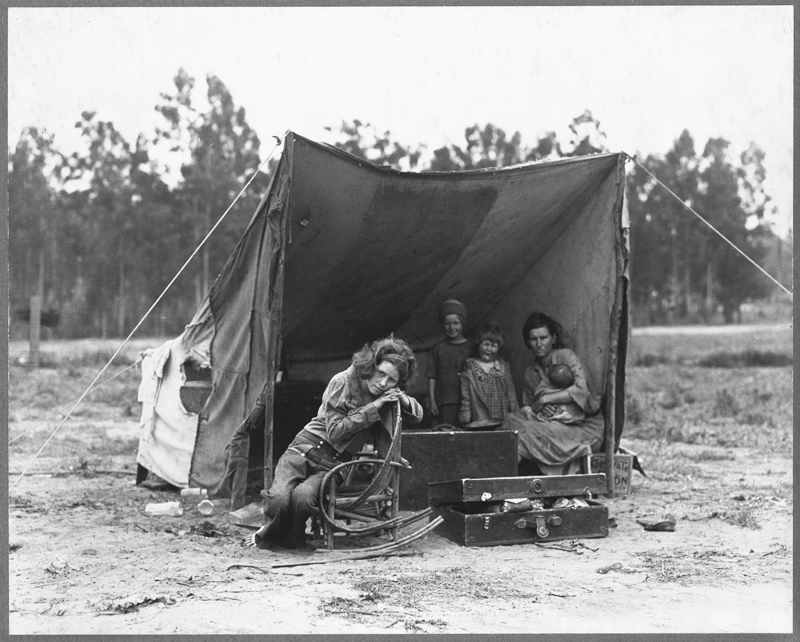

FSA photographer Dorothea Lange came across Florence Thompson and her children in a pea pickers' camp in Nipomo, California, in March 1936. Credit: Courtesy of Library of Congress

Q: Do you remember when you first read about the Dust Bowl?

A: My dad was really smart, an anthropologist, and so it's hard to say that I learned it first at school, but I do remember mentions of it in school. Maybe it was Dorothea Lange’s famous photograph of the migrant farm mother, maybe it was a picture of a dust storm. But it's almost never taught. People remember the Depression and the New Deal with a much more clarity because the argument about big government or less government is a perennial conversation. But for me, this project was brought to life by my production partner, Dayton Duncan, whom I've worked with for more than 20 years. He'd written a nonfiction book called “Miles from Nowhere” about those counties that still have fewer than two people per square mile, which used to be the definition of the frontier. Some of those were Dust Bowl counties. He encouraged Tim Egan, who is the great writer who did "The Worst Hard Time," which is an extraordinary book about the Dust Bowl. He is in our film, and was an advisor to our film. As we saw light at the end of the tunnel after a very long multi-year project on the history of the national parks, and coming off another experience I had working with a different producer on the history of the Second World War, Dayton and I decided we needed to go see if there were enough living folks who could narrate our story to make it worthwhile to dive deeply into the Dust Bowl. Fortunately we were able to find folks who were kids and teenagers then, but their memories are no less reliable and no less powerful.

Q: This might feel like a stretch, but characters in “The Dust Bowl” honestly reminded me of Holocaust survivors who are in their eighties. This the last opportunity to capture their stories.

A: We are beginning to understand that war almost necessarily creates post traumatic stress, but we have come recently to understand that many other things do too. I lost my mother to cancer when I was 11 years old, and there was never a moment when I was aware that she wasn't desperately ill, which is a kind of traumatic experience. Everyone has traumatic experiences like that. The Dust Bowl must have been a ten-year apocalyptic event -- I won’t call it a holocaust because we need to honor that event -- but you'll see people in the film who break down and cry, remembering in their late eighties and early nineties, about the death of a sibling who had not reached 2 1/2 years old, a little sister who died early in 1935, which is an awfully long time ago. They break down as if that event had happened yesterday. It begins to tell you how present memory is, and how important it is for us to ask these questions and try to access these memories, however painful that might be. There's a healing that can take place in the talking about it. We found it with World War II veterans and we find everywhere. These traumatic events live on inside people, and I think we have an obligation to hear them out.

Q: The film does have so many deeply tragic, and occasionally violent, moments, like the scene with the jackrabbits, and the stories about shooting the cows. Did you rein that in or temper it a bit?

A: All editing is a centering process. I come from New England, where we make maple syrup, and it takes 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of maple syrup. So what we do [in filmmaking] is a distillation process. In any given scene, you have a lot more [material] that you can use, and some scenes you want to do more, and sometimes you want to do less. It's always a careful calibration, particularly in the film with what were called “rabbit drives,” when the ecology of [the Dust Bowl] had become so out of balance because of the plowing up of the grasslands, the drought that had come in as a result of the normal climate there, a new wave of hard times, and then the dust blowing because the crops were failing. Jack rabbits would swarm and eat everything that was remaining -- family gardens and lawns and grasses and trees -- and [people] would have these grisly rabbit drives that would beat them to death. It's very carefully modulated in the film. There was a lot more that we could have put in and didn't just out of the fact that this is already a sustaining tragedy in which heroic perseverance is an important value, but you don’t ever want to overload it. That's what I get paid to do: decide how long certain stuff goes on. We found this in the World War II series where people are describing horrible things, and you need to balance that with other things.

Q: So a film like this can makes one feel fearful and powerless. What do you suggest that say consumers in California do to help prevent in another Dust Bowl?

A: Well, I'd like to take the word "consumers" off and just say, "citizens." I think that human beings and maybe particularly Americans -- I don't know enough about other people to make a categorical judgment -- don't plan for the long term. The Dust Bowl is the greatest man-made ecological disaster in American history so far. What makes us fearful is that we see all of the ingredients for other disasters, like the fragility of our oceans and their potential collapse and other droughts that are bringing new dust storms this year. And while we have technology that is bringing up ancient water from the Ogallala Aquifer and drenching our crops [in the Great Plains] to keep the soil in place, that water will run out. We are mining that water. It's not a sustainable source. So one hopes that a film like ours will be part of a conversation about long term planning, about sustainability, about asking the very basic questions that we often don't ask, particularly in urban areas, about where our food comes from. Now the good news is that for the last 30 or 40 years there has been an amazing movement about whole and organic foods, about eating sustainably, about eating local foods, about respecting the environment, and so there is within our larger, mostly ignorant culture people who are striving to live better lives in relationship to the land and their food sources. The Dust Bowl will come as no surprise to them even though the information might be utterly new, just because they have a sensitivity to nature. Now the question is: How do we bring it out to other folks who might change their ways. I live in a little rural town in New Hampshire and in recent years the nearby farmers who hay our open fields have switched to organic farming, and they need to make sure that I don't do anything to the field and that they don't do anything to the field that would jeopardize their ability to certify the hay that they harvest as organic. [That’s an] amazing change for farm families that have been there in some cases in our town for more than 200 years.

Q: Speaking of the Ogallala Aquifer, which is now used to irrigate the area that was once the Dust Bowl as well as much of the plains, can you tell us more about its future?

A: There are some places where it has run out. It's a big vast underground cistern that is irregular in size and basically collected a lot of water as the last Ice Age retreated, so it's not being replenished by rainwater. It's down too far. And some people -- the Cassandras who worry about it -- think it has 20 more years, and others are saying it has 50 more years. But it's a finite period, and it will run out. I'm not suggesting that the Dust Bowl will immediately reappear. We do have time to plan for that eventuality. We do have time to moderate our use of [the water]. We are spending an awful lot irrigating incredibly thirsty crops. Wheat is relatively easy to grow and requires minimal moisture, which is why it was possible in those slightly wetter years to have good wheat crops in a place where they shouldn't have been planting at all. They're still planting down there, and they're not just planting wheat. They're planting feed corn, and corn is just incredibly thirsty. This is part of the bargain we have to make: What will we use our resources for?

Q: Are there any policies that are in the works that will help deal with the eventuality?

A: You know, planning long term is a political football that is so difficult for anyone to exhibit any courage with. There are so many interlocking things. The government pays a great deal of people on the plains and elsewhere in agriculture not to plant crops. It's a subsidy that doesn't appear to them like welfare, but they look in disdain at social programs that help the poorest people just rise up from starvation and real abject poverty to a livable poverty. So you have great conflicting interests in the country about dealing with these things. That’s where the real fear ought to come from: the fact that we find it very difficult to reach compromise and consensus about long term planning that would help to obviate the impending crises and help to mitigate the ones that will inevitably come up.

Ken Burns being interviewed at KQED. Photo: Wendy Goodfriend

Q: Are you at all optimistic that progress will be made?

A: Of course! I make history. History is all about the future. You don’t make history unless you think that we can't take something from the past and transform it into action in the present.

Q: There are dust storms on the rise in the southwest. What can you tell us about those?

A: They are very few and far between. There are always dust storms. This happens when you have loose stuff on the ground and winds. You get dust storms under certain weather conditions, so that will always be happening. Phoenix, for example, had a dust storm in 2011 that was quite significant and dramatic, but nowhere near the size, length, scope, duration and frequency as what happened in the Dust Bowl. And they're in a desert, so it's not inconceivable that dry air and cold air from the north and winds combine to make a dust storm. What we are now seeing though is the possibility that with the combination of drought, winds, and crops that have failed, some of that exposed top soil will blow again. A lot of people are doing stuff. I met a farmer from Iowa who is a “no-till” farmer, that is to say, a lot of people do “clean-till”: they get all of the organic material out of the last season's crop and have that big moist dirt, but that's also in drought susceptible to blowing. And it doesn't retain the moisture; the moisture just seeps through. So if you leave a lot of organic material in [the dirt], it traps and captures the moisture, and the yields are just as great. So I think we are learning, and struggling, but inevitably it is always slow to find consensus. It's interesting that the Dust Bowl, the crisis that it was, precipitated relatively quick action: These independent farmers who didn't want anyone, particularly the government, telling them what to do, within a couple of years are going to the government and saying, “Tell us what to do.” The soil conservation service, in the form of Howard Finnell -- one of the great heroes of this story -- started instituting extraordinary measures about how to plow differently, [as with] contour plowing, and how to rotate crops, how to save as much moisture as you can, how to return some land to grassland. Lots of wonderful restoration that is still in place and farmers are still trying to practice in the Dust Bowl area.

Q: One thing I didn't understand in terms of the mechanics of the Dust Bowl and subsequent recovery was how any recovery was possible if the top soil all blew away? What was left to work with?

A: Sometimes nothing, and that was the ecological disaster. There are still some places that are unfarmable because of the sand dunes there. A lot of that land has been bought up and is being returned to grassland, and a lot of it has been remediated. You can bulldoze the sand level, and you can add organic material, and you can begin to develop replacement top soil, but the hard pan, just below the top soil that was exposed, you can’t break it up with the heel of your boot.

Q: What does No Man's Land -- the epicenter of the Dust Bowl -- look like now?

A: It's still heavily agricultural. They're drawing on Ogallala water. There are places that look exactly like a desert. The grasslands are within that area that the United States has bought and created national grasslands. They are very arid. They don't seem to us exactly what we would think grasslands would be like; they seem almost at the edge of a desert. And they are plagued by the contemporary droughts right now, and fires that go through, and lightning strikes. All of a sudden a stand of cottonwood trees that line a dry river that only runs for a few short weeks in the spring after the snow melt looks like charred stumps. It's a forbidding place, but you also see where the irrigation has come in and people are growing all sorts of crops, not just wheat.

Q: What has been the reaction in the community your film?

A: I think it's been almost uniformly positive. There are a few people that would want to make a little bit of an argument about whether this is truly man-made, but they really don't have a leg to stand on. It's interesting that in Boise City, which is the geographical center of it all and the county seat of Cimarron County and the far western tip of the Oklahoma panhandle, there's still a little godforsaken sign in the middle of the town square that says, "Pray for Rain." It's always, "If it rains, if it rains, if it rains." "Rain follows the plow" was one of the most ridiculous, completely bogus theories that the very act of plowing would bring more rain. It was invented by real estate speculators who were trying to make a killing selling farm land to people who couldn't afford other, richer, more viable farm land.

Q: Are there particular communities that you're doing a push in with the film to try and change attitudes?

A: We aren't trying to change attitudes. What we're trying to do is make good films, and good films hopefully are good stories. We want to share those stories, and what people do with them is what they do with them. We inevitably have a promotional campaign for every film, and we began last April, on the anniversary of Black Sunday, the worst storm of all, April 14, 1935, we assembled in Goodwill, Oklahoma, a tiny, tiny town as many of the survivors that we interviewed as possible. We've already lost a few and have lost some since then, and then we go around to major American cities, but also in Oklahoma and Texas and other places and show them clips of the film and talk to people and show them. We see it as a human drama and an oral history. And then what people do, and the kind of conversation that will be promoted all remains to be seen. But part of being in San Francisco is to take people, and there are very few farms in San Francisco, and talk to them about a farming subject. Because it is always an important stop along the way of promoting our films.

Q: What does the companion book, “The Dust Bowl” have in it that the film doesn’t?

A: Well, Dayton Duncan, who wrote the film and conducted most of the interviews, and is really the author of this project, is a writer in addition to being a producer. The book affords him the opportunity to re-present the story in a different medium and allows him to expand the things that editing necessarily, because of the exigencies of film, require us to take out. He could add more detail that might bog a film down but doesn't bog a book down. So it's a thrilling thing for him that after we lock the film, he has this creative outlet that expands what the film has. At the same time, the film will reach many millions more people than the book will.

Q: Do you have any opinions about Prop 37, the proposition about labeling genetically modified foods that did not pass in California.

A: I have a child who has a peanut allergy, and we're beginning to wonder whether in fact many of these allergies that are cropping up among kids that didn't exist when I was growing up are the result of us genetically modifying various things like soybeans, or other products. So I am very much [in favor], as a concerned parent who has this terrible Damocles hanging over a beautiful little girl, very much for the accurate labeling of what has been genetically modified and what hasn’t. We're finding that the human immune system is not necessarily equipped to handle these slightly modified molecules from the original substance that they may be completely tolerant of. For that little girl's reasons, and a million more, I'm sorry it didn't pass.