As you may have noticed, nori is the new potato chip. Or at least that’s how marketers are trying to position it. Slightly salty with a delicate crunch, snack-sized sheets of roasted nori have become popular munchies for adults and kids alike. These seaweed “crisps” are crowd pleasers not only because of the taste, texture and low calorie count, but because we figure that eating any kind of vegetable – even if it’s from the ocean – must be good for us. More and more parents are tossing those nifty seaweed snack-packs into school lunch boxes, relieved to have finally found something green that their children will eat.

But what do we really know about the benefits of eating seaweeds? Long a staple in Asian countries, most westerners are fairly new to the sea veggie scene. The popularity of seaweeds in the U.S. has been on the rise because they are indeed nutritious – and because recent studies point to health benefits ranging from weight loss to cancer prevention. Although it is decidedly a good move to add some seaweed to your dietary mix, there are a few things worth considering about the promise and safety of eating these marine greens, before you dive in.

Seaweeds 101

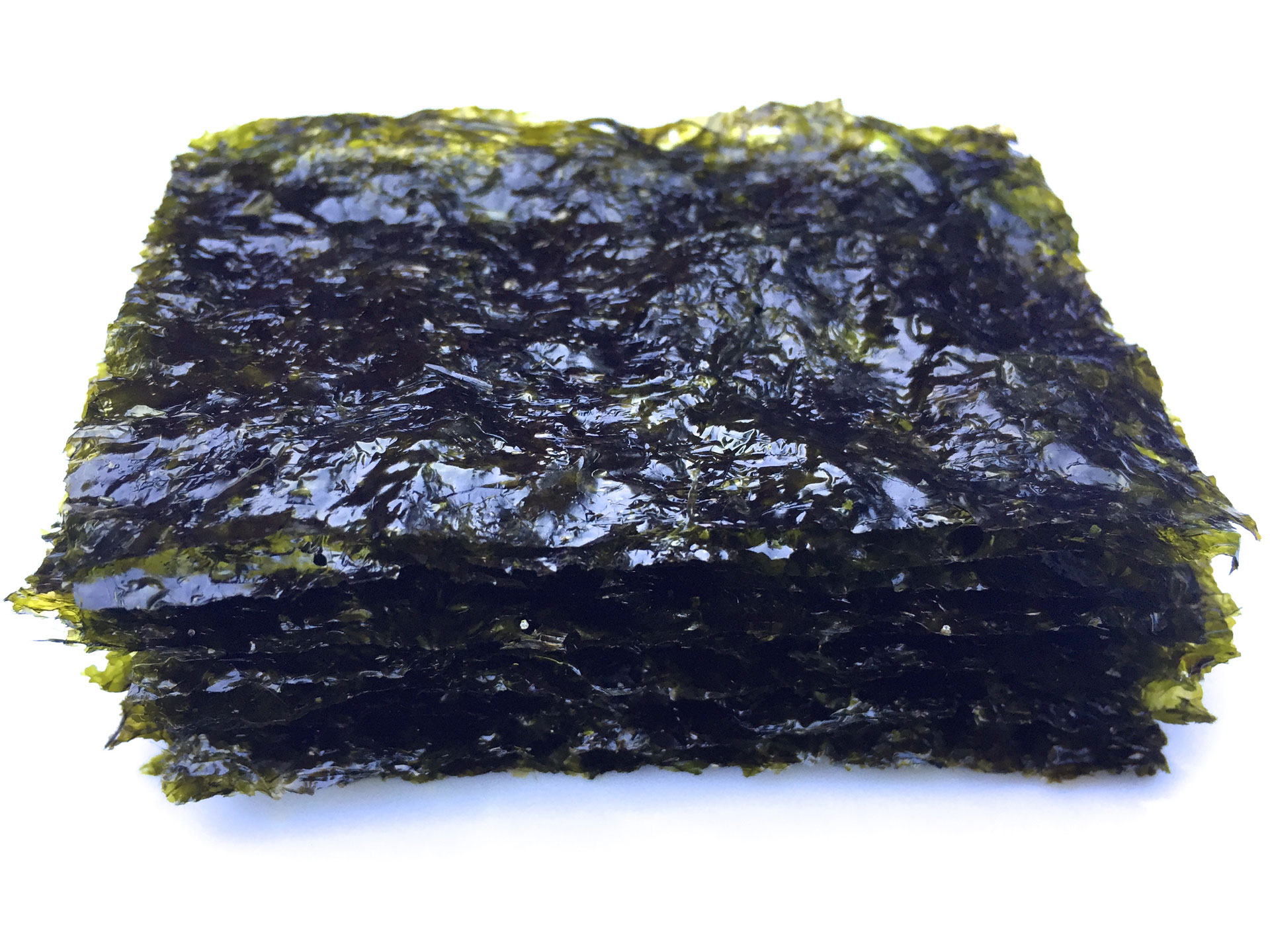

There are thousands of kinds of seaweed, but only a small fraction are typically eaten. Members of the algae family, seaweeds are categorized into three varieties: brown, red and green. Brown seaweed, which includes kelp and wakame, is the most commonly consumed worldwide, followed closely by red. Red seaweed encompasses dulse and all types of nori, which holds our sushi rolls together and fills those snack-packs sold by Trader Joes, SeaSnax, and Marin County based GimMe Seaweed (owned by Annie Chun). Of the less popular green seaweeds, sea lettuces are among the variety most frequently eaten.

Seaweeds can be eaten fresh from the sea, but are more often dried and then roasted or reconstituted to their original form and incorporated into soups or salads. Just like the land-grown vegetables that we eat, seaweeds are cultivated and harvested commercially. Although harvested around the globe, China is responsible for nearly 60% of the world’s seaweed production. Much of the nori that is packaged and sold in the U.S. seems to be farmed in Korea, although more locally sourced seaweeds are sold by smaller companies such as Rising Tide Sea Vegetables, which hand-harvests wild seaweeds off the Mendocino Coast.

Fiber, Protein and Iodine Powerhouses

Seaweeds provide nutrients such as calcium and vitamins A, B-6 and C. Many seaweeds are also loaded with fiber and protein. But seaweed’s biggest claim to nutritional fame is that it is packed with iodine, a mineral that is essential for maintaining a healthy thyroid, which regulates our hormone levels.