“Your homework is to read chapter three and answer questions 1-10. There will be a quiz tomorrow.”

If you teach anything with a text, chances are you have assigned this homework. In my first year of teaching language arts, I was guilty of it as well. I spent hours writing reading questions and composing comprehension quizzes that, really, were nothing more than a “Gotcha! You didn’t read!” test. It should have come as no surprise when my students came to class with little to say about the night’s reading beyond those ten assigned questions. And that was the best case scenario. At worst, I had students who did not do the reading but copied the answers from friends or who simply skimming for the answers rather than reading deeply.

After that first year, I decided to question my own reading practices. What do critical readers naturally do? How do we question the text, make predictions, see patterns unfold? When I crack open a work of fiction or journalism, I go in with an inquisitive mindset. I expect the text to be challenging and thrust me into a world that is unfamiliar. I assume that I will need to get to know the characters the way I would get to know a new friend. I question the context and study-up on the historical background. I seek out patterns of ideas, which ultimately lead me to discover themes, symbols and motifs. What I didn’t realize was that these were skills many of my students lacked. They went into a text expecting it to be confusing without understanding that they could make sense of the pieces of the puzzle through their own inquiry.

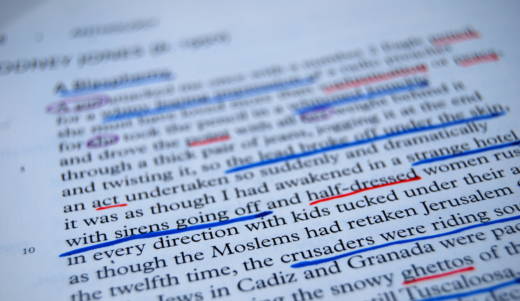

So, I threw out the reading questions. Instead I began asking students to “talk to the text” and write down everything that comes to mind while they read a chapter. Now, when a new school year begins, I model what this thinking process looks like. I pass out loads of Post-Its and arm students with colorful pens so that they can make the margins of their books–even checked out ones–look like personal copies. I read a passage, and then add my commentary so they can see that it’s not an intimidating process. Oh, and I give them a handy dandy bookmark with suggestions.

Here are things I tell students to look for as they begin to form an annotation habit.

1. Summarize.

It sounds simple, but the first step to reading critically is comprehending the text completely. For many students, jotting down the main plot points at the end of a chunk of reading may help them make sense of the action and retain the material. This is also a great jumping-off point for reluctant readers or students who are less than enthusiastic about your plan to have them actively engage with the text. Asking unmotivated students to summarize the previous chapter may seem more manageable and less of a personal risk, since they don’t have to make any self-to-text comments.

2. Question the text.

I often tell students that questioning the text can be anything from clarifying questions, “Where do they speak Farsi?” to contextual, “What were the relations between the U.S. and Iran in 1972?” to analytical, “I wonder what daily life would have been like for Firoozeh and her family with regards to the country’s political climate?” Other common question that arise tend to be

- Who are these people? What are their motivations? What world are they living in?

- What is the context? Time period? Important historical markers?

- Where is the story located? Is place critical to the story?

- What might happen next based on foreshadowing or archetypal story patterns?

- Do you see any common patterns or emerging themes?

3. Make predictions.

Students who can track patterns are more likely to notice themes and connections between a novel and what is happening in the world around them or between a primary source document and current events. Predictions help fuel discussions and sets students up for the next phase of learning, be it a formal writing assignment or a class discussion.

4. Define and clarify.

For many reluctant readers, vocabulary can be a huge road block both to understanding the text and actually completing the reading. Encourage students to take note of unfamiliar terms and define those terms in the margins (or on Post-its). I like to tell them that they don’t need to have the lengthy dictionary definition, but a synonym that helps them access the meaning of the sentence can do the trick. The same principle applies to proper nouns, dates or historical references that may be unfamiliar. A quick Google search might be the difference between feeling completely confused by Amy Tan’s reference to San Francisco’s Sunset district and truly being able to imagine her walking around the city.

5. Draw connections.

When I read, I can’t stop myself from seeing the universal truths on the page represented in daily life. And I’m sure social studies teachers realize that the cliché “history repeats itself” is all too present in national and world affairs. This isn’t always obvious to students though, especially since they still have relatively few life experiences. This is where teachers have a great opportunity to model the type of critical thinking that might link a letter by Frederick Douglass or James Baldwin to a more current essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates or Roxane Gay.

6. Infer and analyze.

This is the hard part for many students. How do we get them to see patterns and translate that into some meaningful observations? I often ask students to take note of a specific idea. For example, when reading Funny in Farsi by Firoozeh Dumas, I ask students to underline any examples that demonstrate a time when language was a barrier or created confusion for her immigrant family. They may not realize it at the time, but later, when I have them step back and look at the text, they can see that the power of language is a clear theme in her memoir.