“What good is having the right to sit at a lunch counter if you can’t afford to buy a hamburger?”

— Martin Luther King, Jr.

In late August 1963, on the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, a quarter million demonstrators converged on the National Mall in the nation's capital to partake in what would become one of the largest human rights demonstrations in United States history.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom drew a majority African American presence. Demonstrators arrived by the busload -- many from Southern states where Jim Crow segregation policies were still alive and well -- to demand an improvement in civil and economic rights. They marched peacefully towards the Lincoln Memorial, where they listened to the impassioned speeches of some of most outspoken civil rights leaders of the day. Most famously, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his seminal "I Have a Dream" address.

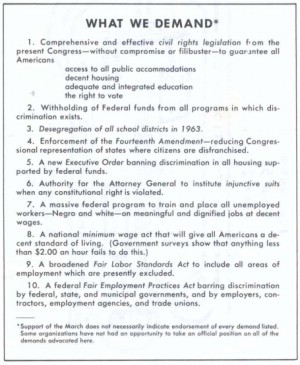

King and other leaders of the march articulated a clear, carefully crafted set of demands, underscoring, as King stated, "the fierce urgency of now."

The mandates included the passage of new binding pieces of civil rights legislation that, among other things, guaranteed voting rights, increased political representation in Congress, eliminated school segregation and imposed heavy financial and legal penalties against agencies that violated the Equal Protection Clause.

The mandates included the passage of new binding pieces of civil rights legislation that, among other things, guaranteed voting rights, increased political representation in Congress, eliminated school segregation and imposed heavy financial and legal penalties against agencies that violated the Equal Protection Clause.

But equally important, although often overshadowed, was the demand for greater economic equality. The movement's leaders called for a federal jobs program and a nearly two-fold increase in the national minimum wage, to $2 an hour (equivalent to about $13 today). Leaders also urged federal enforcement to curtail employment discrimination, as well as policies and programs that would increase access to decent housing and adequate public accommodations.

In his speech that day, King emphasized the urgency of these goals :

"But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition."

The ongoing actions of the Civil Rights Movement were indisputably successful in prompting tremendous progress: less than a year later, congress passed the sweeping Civil Rights Act of 1964, and by 1965, the Voting Rights Act was signed into law as well (although it was largely dismantled by the Supreme Court in 2013). Today, 50 years hence, the results of these victories, and the subsequent gains in equality are evident, marked not least by the election of America's first black president, a milestone nearly unimaginable in King's day.

Today, high school graduation rates among blacks have nearly quadrupled. Black voter participation has grown markedly, as has life expectancy.

On August 28, 2013, thousands gathered on the National Mall to commemorate the 1963 march and the tremendous impact it had. Some of the featured speakers, though, noted that many of the 1963 demands have still not been met, particularly along economic lines. Standing in the footsteps of King at the Lincoln Memorial, President Obama underscored this sentiment:

"In some ways, though, the securing of civil rights, voting rights, the eradication of legalized discrimination -- the very significance of these victories may have obscured a second goal of the march, for the men and women who gathered 50 years ago were not there in search of some abstract idea. They were there seeking jobs as well as justice not just the absence of oppression but the presence of economic opportunity. For what does it profit a man, Dr. King would ask, to sit at an integrated lunch counter if he can't afford the meal?"

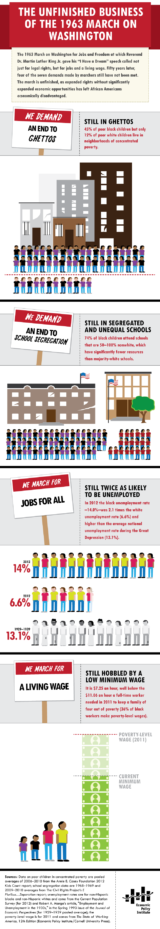

Even as an increasing number of African Americans today have successfully risen the class ladder, attaining prominent positions in politics, business, and academia, huge economic gaps remain between the black and white population in America. The majority of black children today grow up in areas of concentrated poverty and attend segregated, often severely under-resourced schools. The unemployment rate among African-Americans is double that of whites, and more than a third of black adults with jobs work for poverty level wages, according to the liberal-leaning Economic Policy Institute. (The infographic, at right -- produced by EPI -- illustrates some of the March's "unfinished business").

Even as an increasing number of African Americans today have successfully risen the class ladder, attaining prominent positions in politics, business, and academia, huge economic gaps remain between the black and white population in America. The majority of black children today grow up in areas of concentrated poverty and attend segregated, often severely under-resourced schools. The unemployment rate among African-Americans is double that of whites, and more than a third of black adults with jobs work for poverty level wages, according to the liberal-leaning Economic Policy Institute. (The infographic, at right -- produced by EPI -- illustrates some of the March's "unfinished business").

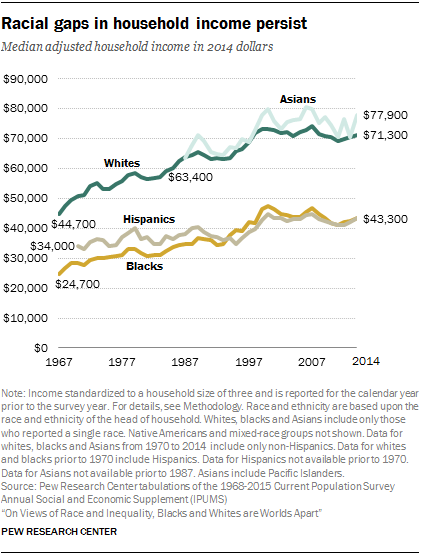

Meanwhile, the black poverty rate is more than double that of whites, while average annual household income is almost $30,000 less, according to Pew Research. Today, African-Americans are also disproportionately represented in the nation's prison population: the rate of imprisonment among adult black males is more than six times that of white males, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Blacks are also victims of homicide at significantly higher rates than any other race.

The series of interactive charts below illustrates where certain primarily economic gaps between America's white and black population have narrowed, widened, or remained pretty much the same. This is obviously not a comprehensive list.

Most of the data was collected by Pew Research, which offers a more detailed analysis of some of these figures, including relative rates for Hispanics and Asians, where data are available.

Note: In 2015, there were about 46.3 million black people living in the United States, comprising more than 13 percent of the population, according to the U.S. Census. In contrast, there were roughly 195.5 million non-Hispanic whites in 2015, or roughly 61 percent of the population. Unless otherwise noted, the figures below include rates for total white and black populations (not just non-Hispanic).

Where gaps have narrowed

Where gaps have widened or stayed the same

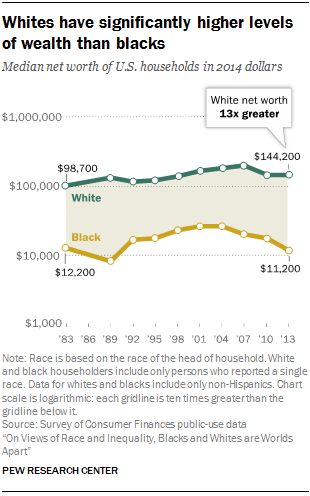

Income and wealth

One of the biggest indications of continued, and in some instances widening, economic inequality between blacks and whites is changing median net worth, with net worth defined as assets (what you own) minus debt (what you owe). In 1984, the median net worth of black households was less than 1/10th (9%) that of white households, according to Pew Research. But since then, the gap has widened even further (as it has between white and Hispanic households). By 2013, the net worth of white households had risen to 13 times that of black households.