As an adult, and throughout her childhood, Williams learned how to compensate for her inability to read. For much of her life, preparing for a trip to the grocery store meant sitting down to sketch out a list – not of words, but drawings. “I had to literally draw a peanut and then some grapes. So the peanuts represent a jar of peanut butter; the grapes represent ‘get some grape jelly,’” she said. “I learned to be a pretty good artist, so it was gifts that I accumulated to survive.”

Among adults, 1 in 5 Americans has low literacy in English – most of whom are born here. Around 8.5 million adults are functionally illiterate. Among children in the United States, just a third of fourth and eighth graders are proficient readers. And the needle hasn’t moved much over the last decade.

Activists in Oakland, California, where Williams lives, have been pushing schools to focus on how students are being taught to read as a way to improve literacy. Members of the NAACP and an advocacy organization called Oakland REACH, started by Oakland parents whose kids attend the district’s lowest performing schools, have coalesced around a campaign for better reading instruction they’re calling Literacy for All. Williams is one of its most outspoken members.

Struggles in School

Williams grew up in Florida in a small panhandle town where racism and violence could be found even in its name, Perry, a confederate colonel.

During a brutal series of lynchings in the ‘20s a white mob burned down the town’s school for Black children. In the mid ‘60s, when Williams started kindergarten, there was a single school for Black children. The school district was so slow to desegregate it lost federal funds in the late ‘60s for violating the Civil Rights Act.

It was a tense school environment that Williams said left scars. “My last memory of that was this Caucasian woman coming in with a gun threatening to kill all of us. At that time, they would call us n*****s,” Williams said. “We hid under the desk, locked in our rooms, terrified.”

For the next few years her family moved around, following the whims of her dad’s military career. During those years, school was a blur of teachers and classrooms across Florida, North Carolina and New York, among others.

The family finally landed in Oakland, where for years Black leaders had been demanding the school board address segregation, protesting the concentration of resources in the mostly white hills schools. In the flatlands, where most Black children went to school, teachers were less experienced, classes more crowded and supplies limited.

In 1967, 6th graders in the flatlands were two grades behind in reading on average. Students in the hills schools were above average. Black organizers were considering calling a school boycott and threatening to create their own school board a couple years before Williams got there.

At 11 years old, she enrolled in Lockwood Elementary, a flatlands school in East Oakland. She was still struggling to read and other kids teased her for it.

“Hearing that laughter,” Williams said, “that traumatized me to the point that I was like, ‘Oh, I’m never reading out loud again.’”

She doesn’t remember being tested for a learning disability, and the school district has no record of her being assessed, maybe in part because she’d developed a strategy to avoid reading.

“I had this anger because I see the other kids read and I couldn’t read and then they call me to read and I’m struggling, the kids start laughing, so I shut down and get mad and throw a book or something,” she said. She did whatever she needed to do to get sent to the principal’s office. “I’m doing stuff to get kicked out so nobody knows,” she said.

The tantrums worked, but it was a vicious cycle. She was acting out because she was behind and needed help, but instead getting help she was getting sent home. And at home there was nobody to help. Her mom was busy working two jobs as a waitress and going to school to become a nurse. She was raising three kids basically on her own, because Williams’s dad was usually away for work.

So Williams didn’t get help. But she kept getting passed on from one grade to the next. She figured out other strategies to hide the fact that she couldn’t read: taking classes like PE, JROTC, and music, plus playing sports as much as possible throughout junior high and high school.

She and her friend Annie also developed a buddy system to compensate for each other’s weaknesses. “She would read and I would do the math problems,” Williams said.

Williams doesn’t know whether they actually fooled teachers or gave them a way out of dealing with the problem. Either way, she graduated from McClymonds High School in 1978 without ever really learning to read.

Struggles in Adulthood

Over the years she made other attempts to learn through community colleges and adult literacy programs. But mostly she found ways to get around the fact she couldn’t read.

To get her driver’s license she took the test multiple times, memorizing the different exam sheets until one repeated. When she needed spelling help she called 411. “I would call the operator and say ‘I need to know how to spell so and so and so’ and they would spell it for me,” she said.

In time, it became increasingly clear to Williams that she wasn’t alone in her struggle, and she decided telling her story might help lead to change.

When she first spoke openly about her experience in front of her church community, people both older and younger began confiding in her. “They tell me, ‘I graduated and couldn’t read either,’ and I was like, ‘Wow.’”

Push for Effective Reading Instruction

When it came time for Williams’ three daughters to learn to read in the ‘80s, a new theory of reading instruction called “Whole Language” was spreading through classrooms around the world. It shares ideological roots with the theory behind the Dick and Jane style books Williams grew up with.

The theory embraced reading as a natural process, like learning to talk, and assumed surrounding children with stimulating books was all they needed to pick it up.

At the time there was already mounting research evidence that learning to read is far from a natural process and kids have to be explicitly taught how our written code represents spoken language. For that, nuts and bolts phonics instruction is essential: A child may be able to name the letter “B,” but it’s phonics instruction that teaches them how the “beh” sound is connected to the letter “B.”

By 1987 California embraced whole language ideology and adopted new textbooks that minimized phonics instruction. A few years later, California’s reading scores were among the worst in the country, falling across race and class lines. Whole language wasn’t the only factor, but many saw it as a major contributor.

This was the world Williams’ daughters were educated in. Two of her three daughters struggled with reading, and none of them did well in school. All three ended up dropping out of high school, though they later got their diplomas.

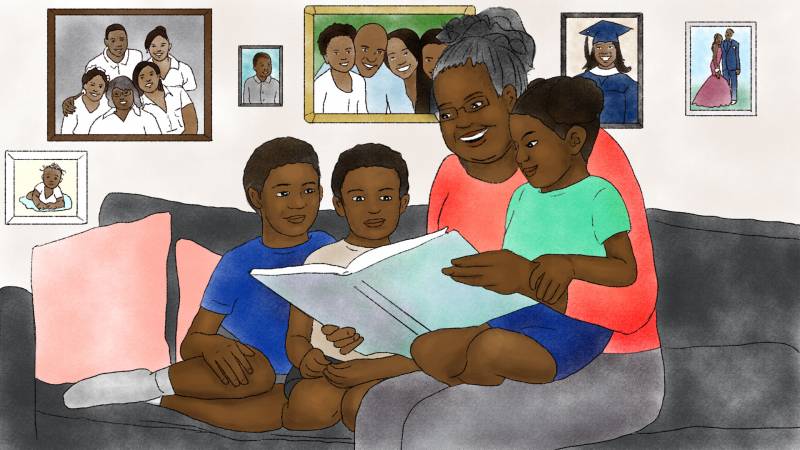

Now Williams is raising four of her grandchildren. She’s fought not to let them slip through the cracks the way she believes she and her daughters did. She’s regularly showing up at their schools, demanding testing for special needs and pushing for progress reports. Despite her efforts all four are behind in reading.

In Oakland, as in districts around the country, that’s not unusual. Today only a third of Oakland Unified students are meeting state reading standards.

Kareem Weaver, a member of the Oakland NAACP’s education committee, said adults need to better serve African-American students, especially if only 18 percent of them are reading with proficiency. “At some point in time you’d think you’d step back and objectively say, ‘Hmm, unless our collective kids are broken and damaged, then maybe it’s something that we’re doing,’” said Weaver.

White students in Oakland are faring better than Black students when it comes to reading — at least in part because white families disproportionately have the means to supplement school reading instruction with their own educational capital, and with paid tutors — but even with those resources, almost a third of white students aren’t meeting state standards either.

For Weaver, the district’s reading scores raise obvious questions. “ How are we teaching them to read? What does the science say?”

In Oakland, like in districts around the country, reading is still taught using some of the same discredited methods that failed Williams and her daughters, despite the robust and largely settled body of research that supports the views of phonics champions.

Weaver argues because of the way racism and poverty stack the odds against so many Oakland students, it’s essential teachers use the approach proven by researchers to give the most kids the best shot becoming strong readers. It’s why he’s working with parents like Williams on a campaign called Literacy for All, a collaboration between the NAACP and the advocacy organization Oakland REACH.

In Search of a Better Way

In order to understand what it is about the district’s current approach to reading that’s not working, and find possible solutions, Weaver visited Oakland classrooms before the Covid-19 pandemic closed down schools in the spring.

At Markham Elementary School in East Oakland, just three percent of kids are meeting state reading standards. Weaver stopped by teacher Sabrina Causey’s first grade class where a literacy specialist, Jessica Sliwerski, had been volunteering to help Causey teach the kids to read.

Together they were trying out a different curriculum from the district standard. It uses a highly systematic approach to reading called structured literacy. Students learn the smallest units of sound and build up to more complex material following a specific sequence.

“We’re really good at hearing the sounds and the words and pulling out those sounds,” Sliwerski told the small group of kids sitting around her on a colorful rug. “Where we need more practice is looking at the letters, making the sounds and blending them to make a word. So, listen, I’ll go first. N-O-T. Not. Your turn.”

For kids who struggle with reading — whether they have a disability like dyslexia, they’re English learners or have limited home exposure to literacy — researchers have found it’s especially important to provide explicit, systematic phonics instruction. But the primary curriculum Causey was expected to use to teach reading in Oakland relies in part on a different theory of how people learn to read — one with roots in that whole-word approach used to teach Connie Williams and her daughters.

“I was going through the lessons and I was like, ‘this is ridiculous,’” Causey said. “How am I supposed to teach my kids that in order to be stronger readers they need to keep on trudging along when half my class doesn’t know basic alphabet sounds?”

Oakland isn’t alone. The curriculum, Lucy Calkins Units of Study, is one of the most popular in the country. But a review by a panel of literacy experts released this year found major problems with it.

A central flaw, accounting to the report, is an approach called “three-cueing” that teaches kids to guess at words based on contextual cues, including pictures. “This is in direct opposition to an enormous body of settled research,” the report authors wrote, adding that it even contradicts other materials within the Units of Study curriculum.

When Weaver visited, even the strongest readers in Causey’s first-grade class were still at a kindergarten level and she expected no more than six students to end the year at grade level.

As for the rest of the kids? “They get pushed through,” Causey said, because the pressure is everywhere. “Administration, the higher ups, the community, parents.”

“Social promotion is what we do because it just looks bad and feels bad to hold them back,” Weaver said.

Not that holding kids back and trying the same approach again would necessarily fix things, Weaver acknowledged. Plus there’s evidence that holding kids back creates its own problems. But Sliwerski said the status quo isn’t working either.

“You can look at the data for the city and you can see how many kids are leaving any given elementary school functionally illiterate,” Sliwerski said, “It just becomes someone else’s problem.”

Oakland school leaders are considering dropping the curriculum they were teaching to adopt something more in line with the research on reading instruction. It’s going to be a long process, and there are already fights brewing about the curriculums under consideration.

Continuing Advocacy

Meanwhile, the Literacy for All coalition is hoping to give parents the tools to spot quality reading instruction and advocate for their kids in school.

At an event as part of that effort, Williams sat at the front of the room with her granddaughter. “I’m excited!” she said, “‘Cause this is my story — this has been my pet peeve about helping us to read.”

Williams joined a group of parents and teachers to talk about state reading assessments and other expectations of students. They took turns introducing themselves.

“My name is Connie, but they call me Momma Williams at the school ‘cause I raise a lot of sand,” she told the group. “I’ve been fighting since my kids was in school, so now to see that it’s considered a state of emergency, I’m very happy to see that.”

Williams was in her element. She offered advice about parents’ rights, fielded questions about navigating special education and delivered a critique of implicit bias in standardized tests. Her granddaughter Mercedes was nearby watching her grandma, looking a little amused. She’d heard all this a million times. But her reading scores are improving.

It took three generations, but for Williams it finally feels like someone is paying attention. “It reached somebody cause I didn’t get tired,” she said. “I didn’t do this in vain; I didn’t do this to have pity. I did this because I didn’t want it to be my kids’ story, it wasn’t going to be my grandkids’ story and it’s definitely not going to be my great grandkids’.”

Listen on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, NPR One, Stitcher, Spotify, TuneIn or wherever you get your podcasts.