Virtual feedback also removed the social barriers that may prevent students from wanting peer feedback. The fear of watching a classmate’s eyebrows furrow as they read was removed from the equation. Some students may have felt less anxiety when they shared personal anecdotes and didn’t have to then look their editors in the eyes.

“When it’s not face-to-face, kids can be a little more vulnerable and a little more specific about the feedback they give, because sometimes in sixth grade, it’s a social thing,” said Reeder.

Much like how anonymity can embolden people on social media, Reeder claimed, there was a level of vulnerability that can be tapped into when writers and editors are separated by screens. Added was the security that students knew that their teacher would see all given feedback, ensuring students’ comments remained kind and helpful.

After seeing the benefits, Reeder decided to keep asynchronous, online peer feedback as an option for the students who returned to her in-person classroom.

Hearing a Human Voice

For her own feedback to students, Reeder began attaching audio notes to assignments. Her students appreciated the ability to hear feedback rather than just read it. Audio feedback also provided students with the option to scroll through their work while listening and to replay feedback while writing.

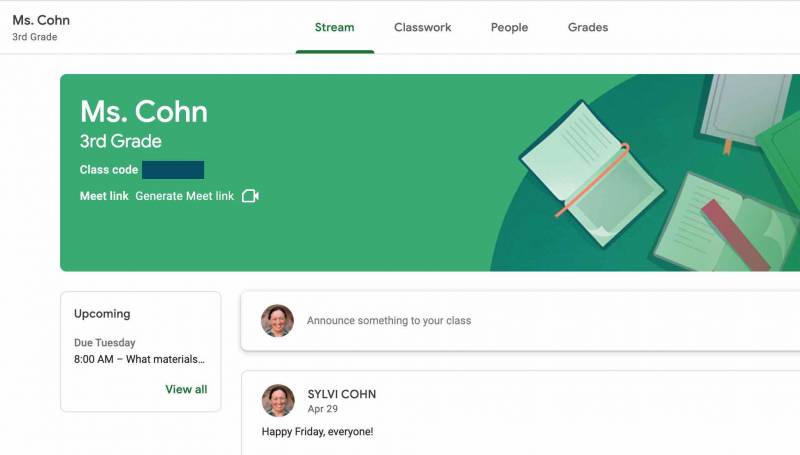

Given the shortened instruction time of online classes, there wasn’t enough time for every student to fully express their thoughts on the reading or participate in a class discussion. So Maribel Parenti, a third grade teacher in Redwood City, California, assigned students audio reflections between one and three minutes, depending on the depth of response necessary, on Google Classroom. Students were asked to reflect on a book’s chapter, provide summaries or explain characters’ actions.

Much in the way students might participate in a classroom, Parenti’s students worked out their thinking by answering out loud. Parenti could check reading comprehension for every student through a metric designed to be less formal than a homework assignment or test. She could then give students feedback by responding to their posts with her own voice recordings, which she found faster to make than writing a response. In her feedback, Parenti could agree with a student’s argument or ask them to expand on certain points — to which her students could then upload an audio reply.

The assignment was specifically to check comprehension, centering thinking processes more than writing skills. Parenti prioritized verbal responses for her students who struggle with reading to increase their comfort with the activity. For her students at or above reading level, she would often write her responses to provide more reading practice.

Early in distance learning, Parenti assigned students handwritten responses, which she struggled to read when held up to the screen. Typed submissions stressed her students struggling with typing and spelling skills. She wanted to explore the different ways her class could have a conversation.

Through audio, she could also hear the voices of her students who tended to not participate in her virtual classroom. Her more reserved and anxious students appreciated the chance to fully participate without observation from their peers. Their responses were given and received privately.

“They’re just talking to themselves or to the computer and no one is seeing them,” she said.

Parenti planned to still offer this participation option when her classroom becomes fully in-person: students who don’t feel comfortable sharing their thoughts in class could have the opportunity to upload them online later, privately and in their own time.

Parenti also provided the option for students to upload video responses on Flipgrid. She called its features “Instagram for kids,” as students can add stickers, face effects and stock image backgrounds. Her students with humorous streaks appreciated the ability to sport virtual glasses and digitally change their hair colors.

For one response, a student chose a newsroom background and delivered his answer with the formality of a nightly newscast anchor. Parenti shared his video with the class to provide inspiration. She watched as students shared ideas and tried out features or techniques their classmates used, receiving new insight into each student’s ingenuity.

“Every single one of them is so different and they’re so creative that I’m just like, ‘Wow,’” she said.

The Upside of Zoom

Aeriale Johnson, a third grade teacher in San Jose, California, helped her students express their creativity through the Zoom chat. This feature specifically allowed students to participate during times when they’d regularly be unable to speak, such as when watching videos or listening to a book. Rather than hold their questions and wait to be called on — running the risk of forgetting or running out of class time — students could type their thoughts, questions and reactions as they came to them, uninterrupted, in the Zoom chat.

During storytime, students put crying emojis during the book’s sad moments and heart emojis during sweet ones. When the class watched videos, Johnson joined them in the chat as they wrote what they saw, thought and wanted to learn more about. Her students asked questions about environmental issues, racial justice and the year 2020. Johnson would pause class to catch up on the chatbox feed, responding to messages and answering questions.

“That also shows you’re not just typing to a chat box for no reason, like, I value what you’re saying and I think that it’s important,” said Johnson.

Zoom’s chat also includes a direct message feature, which Johnson’s students used to talk to her privately. While in-person, a student could come up to her and ask to speak one-on-one, their classmates could still observe that this took place, decreasing the situation’s privacy. With direct messaging, students could ask questions they might not feel comfortable vocalizing in front of the class or typing in the chat.

Harini Shyamsundar, a secondary math teacher in San Pablo, California, shared that her students appreciated the chance to use the Zoom chat during the transitions and uncertainty of virtual learning.

Harini Shyamsundar, a secondary math teacher in San Pablo, California, shared that her students appreciated the chance to use the Zoom chat during the transitions and uncertainty of virtual learning.

“[With] the newness of online learning and the kind of fear and uncertainty that students had around it, the ability to communicate using that chat tool, to privately communicate with the teacher to ask for help in this really not intimidating way, has been huge,” said Shyamsundar.

Using the Zoom chat as a forum space, Shyamsundar encouraged her students to describe concepts and communicate to solve problems. Her students’ ability to privately chat with her to ask for help was something she wanted to keep when her class becomes fully in-person.

“They can maybe put it into some sort of form and I’ll have it on my screen and I can answer it to the whole class,” she said. “I think it would be a really great adaptation to continue.”

By March 2021, Johnson’s third grade class had started asking how to best replicate the chat box when moving back to in-person class. Her students proposed virtual tablets or whiteboards with dry-erase markers — anything that would allow them to respond quickly and occasionally use emojis.

Strategies for Thinking Visually

Kristin Tufo, a middle school science teacher in Portland, Oregon, thought her students might be tired of seeing their own faces after virtual education. So she decided to transform the annual seventh and eighth grade science fair into a podcast series. The episodes tackle questions posed by kindergarteners: Why is snow white? Why is cotton candy fluffy? Why do farts smell?

Without video, her students must rely on their description skills to share their discoveries and relevant scientific processes — sharpening their writing skills.

“It’s good for their writing skills to have to describe things in such a way that little kids can picture it,” said Tufo.

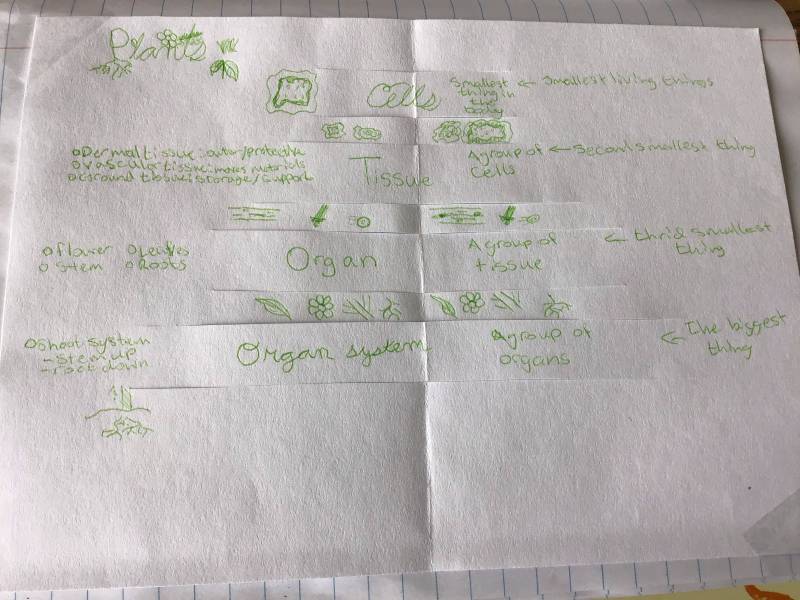

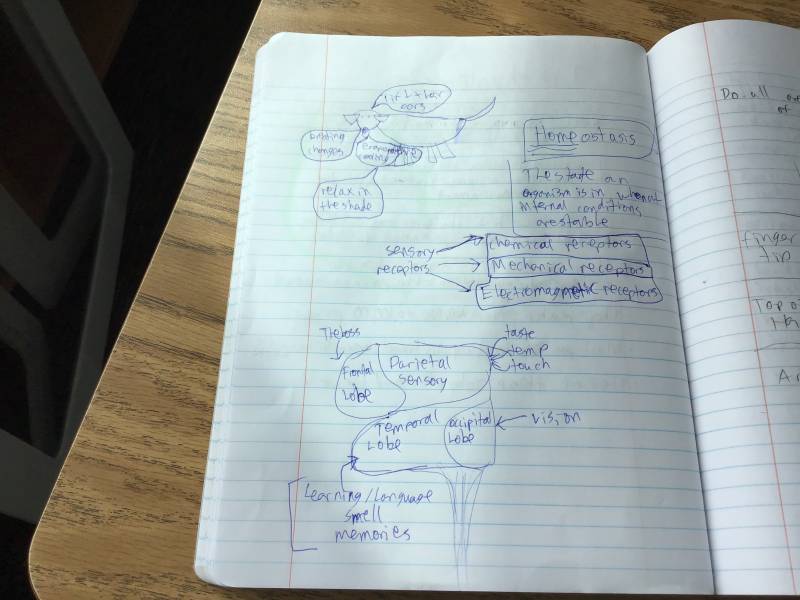

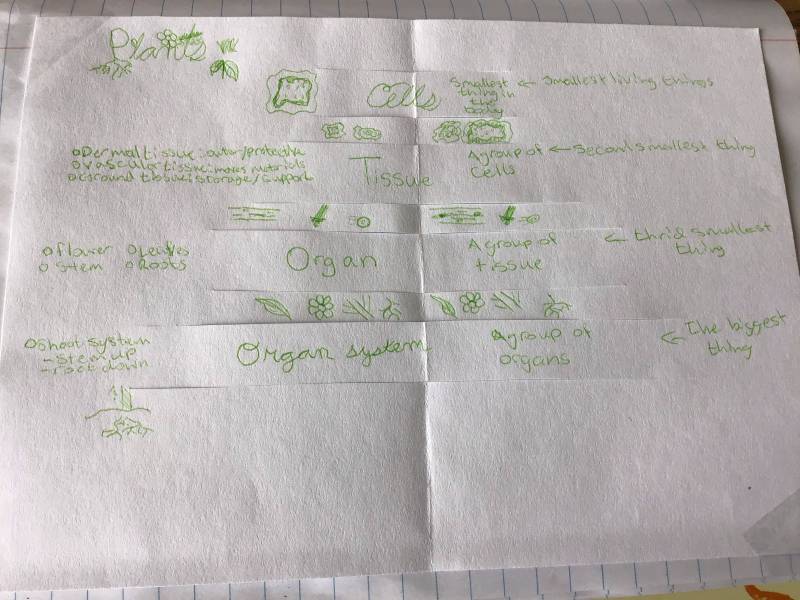

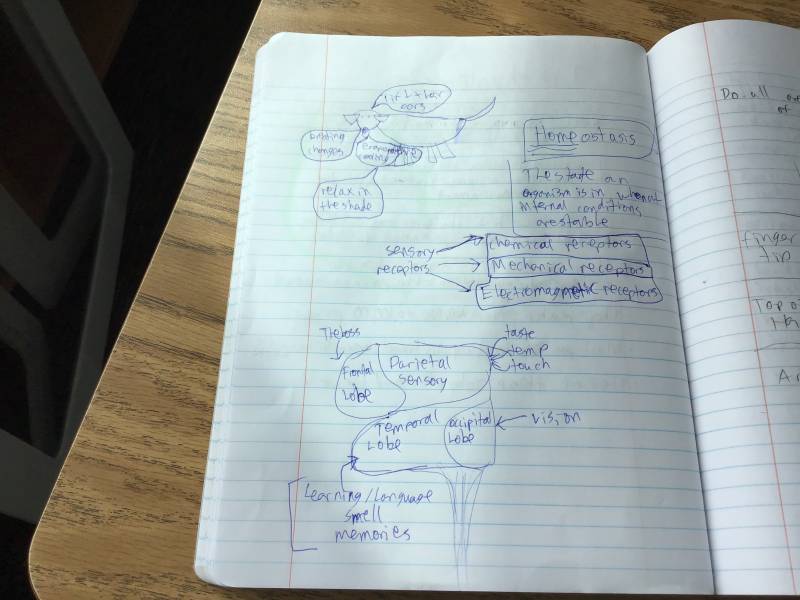

While Tufo previously incorporated visuals into her teaching, her classes prior to virtual education prioritized discussion and demonstration. Wanting to provide visual aids to her lectures, she began taking notes on screen for her students to copy or use as inspiration. She included drawings, a practice known as sketchnoting, to illustrate processes like fossilization or chemical reactions.

“Rather than just watching a video of something, the act of actually writing or trying to draw something that represents it should give them a higher understanding of the idea,” Tufo said.

Tufo turned to this process to convey her lessons and engage her students during decreased lecture times. Wanting to better imprint lessons in their minds, she encouraged her students to write their notes by hand. She cited scientific theories that visual aids and the act of physically writing assist with memory, as well as her training on the importance of the resistance of pen on paper in helping students with dyslexia.

With practice, some of her students who initially lacked confidence in their artistry found they enjoyed incorporating drawings into their notes. Some began sketchnoting in their other classes, too, she said.

Though she didn’t wish to dismiss the gravity of the pandemic, Parenti expressed gratitude that virtual education forced her and other teachers out of their comfort zones and encouraged experimentation with new technologies. These experiments, she expects, will influence education moving forward, like her own third grade class’ option for asynchronous participation.

“Now I have more tools under my belt that I’m going to be able to use with my students once we go back in person,” Parenti said.

Harini Shyamsundar, a secondary math teacher in San Pablo, California, shared that her students appreciated the chance to use the Zoom chat during the transitions and uncertainty of virtual learning.

Harini Shyamsundar, a secondary math teacher in San Pablo, California, shared that her students appreciated the chance to use the Zoom chat during the transitions and uncertainty of virtual learning.