He’s the second U.S. poet laureate to come out of Fresno and the second to walk into KQED’s Central Valley Bureau to record an interview with the San Francisco office.

Four years ago it was Philip Levine. Now enter Juan Felipe Herrera.

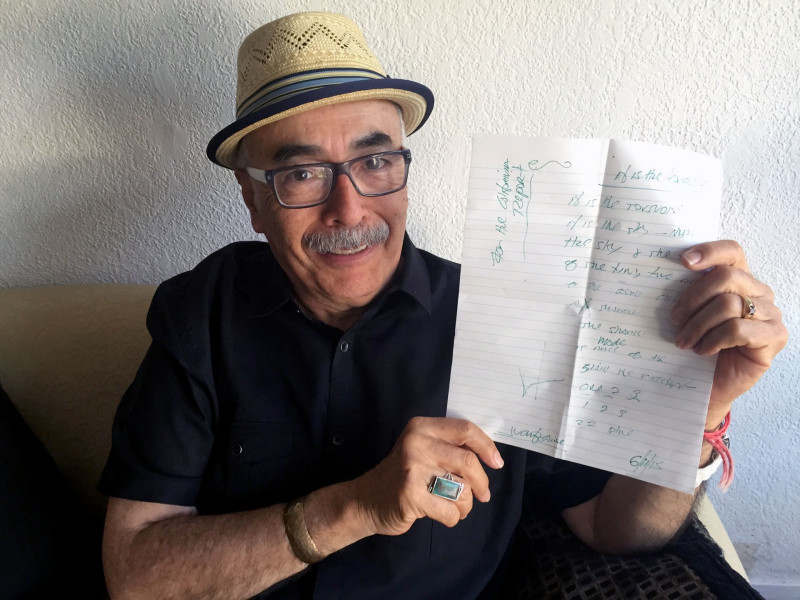

Herrera says he usually wears colorful clothes. But today he’s dressed in black pants, black shoes, black shirt. A local photographer didn’t want his lively garb to take away from the shape and essence and expression of his face. So Herrera first wore the black clothing for an outdoor photo shoot, standing in front of warehouses with graffiti, the poetry of the street. He says his son had to go out and buy him a couple of black shirts — Herrera didn’t have any.

But the black works. It makes room for the canvas that is his face, ever changing in response to what he sees or hears, his eyes twinkling, noting possibility everywhere. He sits down for his interview, headphones on, a microphone in front of him.

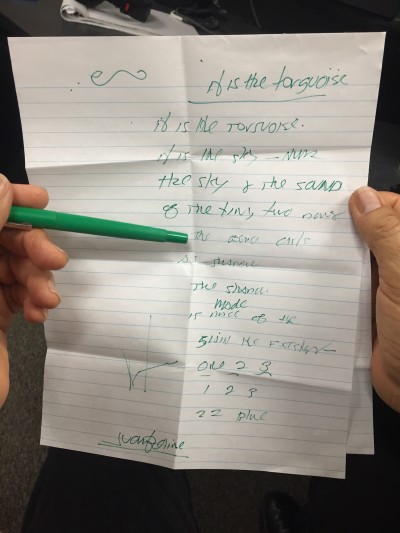

Scott Shafer, the host of The California Report Magazine, asks Herrera if he brought a poem to read. Herrera checks his pockets and looks around as if he might find one in the air. He asks for a sheet of paper and a pen. And even as he talks with Shafer, he starts writing. At first, it seems like he is just recalling a poem from memory, but then it’s clear he’s crafting a new one. He tells Shafer he’s good at doing two things at once.