This fiscal year immigration officials are detaining more people across the country in local jails and private prisons than they did last year.

Typically, the government must detain people before deporting them. The average number of people in immigration detention on any given day nationally increased by 17 percent from fiscal year 2016 to fiscal year 2017, according to data obtained by KQED through a Freedom of Information Act request. Data are only available for the first part of fiscal year 2017 from October 3, 2016 to March 20, 2017. The federal government’s fiscal year begins in October.

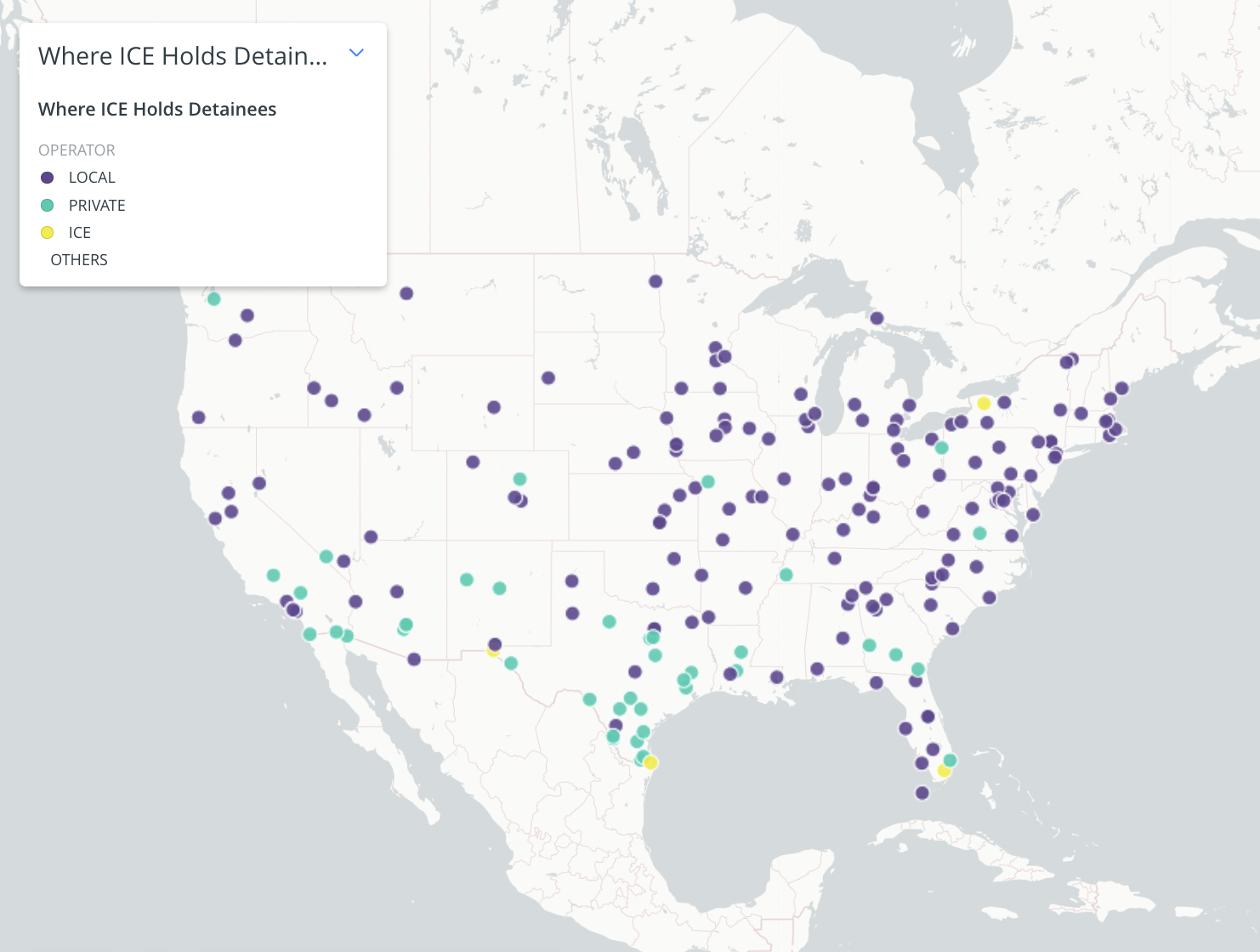

Immigration and Customs Enforcement relies on a network of more than 200 locally operated jails (purple), private prisons (blue) and their own facilities (yellow) to hold all these people.

We can see that ICE has far more contracts with local county and city jails to hold people than with private companies. However, jails can hold only so many people because they’re often smaller than private prisons, and regular jail populations can vary drastically. So, although there are more local jails holding detainees, there are far more detainees in privately operated prisons. When we adjust for population, we can see how many more detainees are in private prisons.