F

or more than two years, Amika Mota was a firefighter in rural Madera County. She and her all-female crew responded to structure fires, vehicle fires, medical calls, car accidents, wildfires — any emergency within a 30 mile radius of the Central California Women’s Facility, a women’s prison in Chowchilla.

They also served the prison, and they slept and ate there. All of them were inmates.

“How often do you see a fire truck roll up and five females step out?” she said, adding that most of the time, people didn’t know she and her crew were inmates. “We’d complete the call with them never knowing. We were just a normal fire department.”

Mota was serving a seven-year sentence for vehicular manslaughter. She ran through a red light in Orange County when she was high on meth, striking and killing 69-year-old Lee Naeng in 2008. She’d struggled for years with drug addiction. Her first contact with the law, she said, occurred when she was 11.

But during her prison term, Mota said she got clean. She worked hard and received the training all firefighters in California must complete. She rose to the top job of engineer, driving the fire trucks. For her work, she was paid 53 cents an hour. And when she was released from prison, she knew she’d never be hired as a full-time firefighter.

“We just kept hearing, ‘You’ll never get hired,'” she said. “It’s just not possible. They won’t hire felons.”

“When I left prison, at that point, I would’ve been happy with the minimum wage job until I figured out if I had the potential for a career because I didn’t know what it would look like coming home,” Mota said. “I thought I would be just lucky to be earning more than 53 cents an hour.”

Mota isn’t alone.

For 1 in 5 Californians, Many Restrictions Last for Life

According to a report released Thursday by the advocacy group Californians for Safety and Justice — which has successfully pushed for past reforms of the state’s criminal justice system — a total of 8 million California residents have criminal convictions on their records that are hampering their ability to find work and housing, secure public benefits or even get admitted to college.

That’s one in five Californians who face a total of 4,800 laws that, according to the report, “impose harmful collateral consequences long after successful completion of a sentence, most of which have no foundation in public safety and serve no purpose other than to make it harder for people to rebuild their lives.”

Most of those restrictions last for life, said Jay Jordan, who chaired the 30-person working group that wrote the report. The group included police officers and a judge. Jordon also served time in prison for a robbery.

“Like myself, I could never adopt a child,” he said. “I could never sell insurance. I could never sell cars. I could never work in health care, never work in government, never work in education — for life.”

As part of the report, Californians for Safety and Justice surveyed more than 2,000 people last year who have criminal convictions. They found that 46 percent have difficulty finding a job, and one-quarter have trouble finding housing.

Formerly incarcerated people also often face another hurdle: paying off fines and fees that pile up over the years before and after a conviction.

Mota’s family is dealing with that. Her husband, who also served time in prison, recently learned that he has $9,000 in court fines and fees dating back 13 years.

“He’s doing everything kind of by the book,” Mota said, noting that her husband has been out for two years after 26 years in prison and is holding a steady job. “And then he got hit with fines and fees going all the way back to 2005 for different court cases.”

That means his $15-an-hour wage is garnished to pay the backlogged fees, Mota said.

Those fines and fees often grow over time, the report says, as collection agencies add sanctions. And they often result in a drivers’ license suspension, further hampering people’s ability to work.

The report notes that these “collateral consequences” don’t just impact the former inmate, they weigh on the entire family. That’s certainly the case for Mota, who just had a baby three months ago.

Jordon hopes the report helps spark changes in state law that would let people more easily expunge their records, or even automatically purge some convictions after a set amount of time.

And at least on principal, it may be one issue reform advocates and law enforcement officials can agree on.

Is it Time for a New Option to Clear Criminal Records?

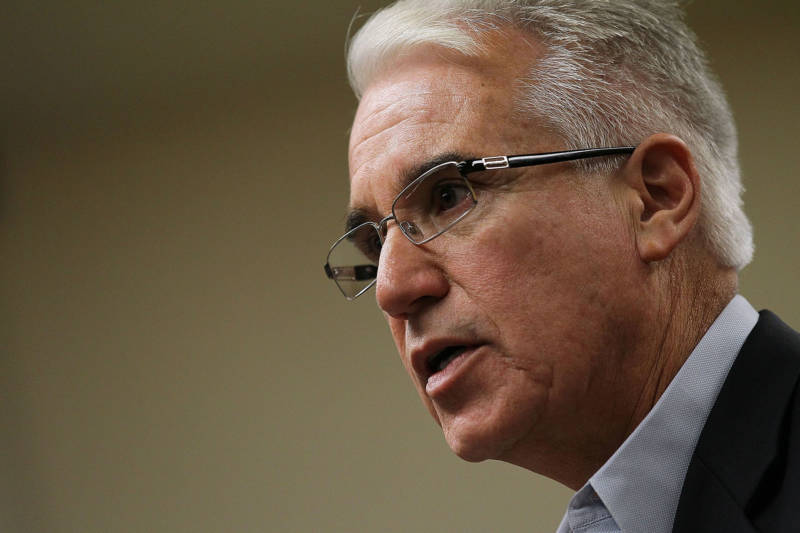

San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón, who is among the more progressive prosecutors in California and has backed many recent reforms, said he’s been looking into this issue for “a long time” and was already hoping to push for state legislation to tackle it.

He’s not alone. San Mateo County District Attorney Steve Wagstaffe has not supported all the changes that have shortened prison terms in recent years — but said the idea of expunging records has merit.

He said that there are currently two avenues to clearing a conviction: a gubernatorial commutation or the sealing of a record. Both options can be hard to attain, and they’re not always useful. Wagstaffe said with so much information in the hands of private companies that publish those criminal records online, it may be time for a new option.

“For many, many crimes, with the passage of time, yes, there ought to be a another, a third avenue where people can get that record where it’s really cleaned off,” he said. “I do support that approach to it.”

Wagstaffe said if a new process was established, it shouldn’t apply to every crime, but for those that qualify. He said it should be automatic — with an option for prosecutors to challenge cases.

Gascón agrees. He was the first prosecutor in the state to announce he was proactively expunging old marijuana convictions, without requiring defendants to initiate the process.

The passage of Proposition 64, legalizing recreational marijuana and applying retroactively to past convictions, opened the door for the program.

“We know that Prop. 64 offered a tremendous amount relief for marijuana convictions,” Gascón said, “but that there are a whole number of other offenses where people have served their time, completed their terms, paid their restitution, done everything we asked them to do and they continue to be impacted by their convictions. They are inhibited from getting good employment, they have problems getting housing, problems coaching their kid’s Little League team.”

“We also know that one of the keys to a successful reentry to society is the broadest possible access to things that most of us have,” Gascón said.

He said he also understands as a former police officer that records can be beneficial to law enforcement.

“We want to make sure we are surgical enough so we are not precluding legitimate law enforcement functions,” he said, “but also that we are not keeping people who are on the straight and narrow from having access to those things we all take for granted and that are so critical to being fully integrated into society.”