The last time Bertha Zúñiga visited San Francisco from her native Honduras was in April 2015, when she watched her mother, Berta Cáceres, walk onstage in a glittery gown to receive the prestigious Goldman Environmental prize, also dubbed the Green Nobel.

Not even a year later, gunmen burst into her mother’s home on the night of March 2, 2016, and shot her to death.

Cáceres was an environmentalist and indigenous rights activist, as well as a 44-year-old mother of four. She had led a years-long grassroots campaign that halted the construction of the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam that Lenca indigenous communities said threatened their supply of food and water in western Honduras.

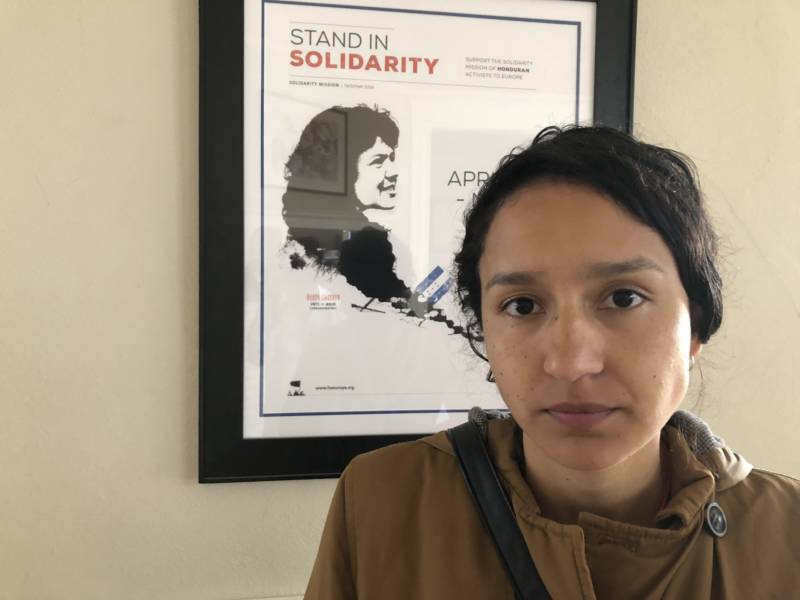

Her daughter, who friends call Berthita, returned to the Bay Area this week to speak before UC Berkeley law students about her mother’s assassination and her family’s struggle to secure justice in the murder case, which has garnered worldwide attention.

A verdict is expected in coming days for eight defendants, but Zúñiga believes those ultimately responsible have not been held to account.

Sitting in her cousin’s kitchen in Oakland, Zúñiga, 28, said Honduran police and prosecutors intentionally botched the investigation, and the trial would not have gone forward without an independent inquiry by international attorneys, including one from UC Berkeley.

She said the murder and the obstacles to a fair trial reveal a climate of violence and impunity in Honduras that is pushing other people to flee the country.

“If justice is not achieved with all the work we’ve done, with all the international declarations and protests, what are the chances an ordinary person can get justice?” asked Zúñiga.

The murder rate in Honduras remains one of the highest in the world, despite a downward trend in recent years. Those responsible are rarely convicted, as abuse and corruption are rampant among the judiciary and police. Many of the Hondurans making their way to the U.S. border in loose caravans say they are escaping that violence.

“They know that the people who commit crimes will never be punished,” said Zúñiga, drinking coffee at the kitchen table.

Zúñiga had flown to the Bay Area from Honduras the day before. She was scheduled to speak Thursday at the UC Berkeley Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic, on a panel with women from Guatemala and Colombia whose family members were also murdered for their activism. Then, Zúñiga planned to catch a plane to be back in Honduras.

She wants to be in Tegucigalpa when a tribunal of judges issues the verdict, which could be as soon as Saturday, Zúñiga said. A total of nine people were indicted, including an ex-military intelligence officer. The president of the Honduran company building the dam Cáceres fought, Desarrollos Energéticos, will face trial separately.

The company has denied any involvement with Cáceres’ murder.

Roxanna Altholz, who co-directs the International Human Rights Clinic at Berkeley Law, said Honduran authorities have withheld and even erased evidence from dozens of computers, cell phones and other electronic devices during the investigation.

“I am very concerned this is a show trial and it’s a trial being used to shield the masterminds, the intellectual authors, from accountability,” said Altholz, who was on the team of international attorneys aiding the family.

Bertha Cáceres is not the only victim of violence against environmentalists in Honduras. A 2015 report published before Cáceres’ death, found 111 environmental activists and land defenders were killed in Honduras since 2002, as the Honduran government issued concessions to private companies for dams, mining and other projects.

For Silvio Carrillo, Zúñiga’s cousin in Oakland, his aunt’s murder was a tragic wake up call.

“I was living in a bubble here in the U.S.... I was missing out on the reality of what was happening in Honduras,” said Carrillo, a journalist who was born and raised in Washington D.C. Carrillo has since worked to alert members of Congress about human rights violations in Honduras.