October 1933 was the heart of the Great Depression. Jobs were in short supply, and thousands of Angelenos were making 40 cents an hour doing cleanup and maintenance work in Griffith Park through a government assistance program.

There were 3,784 workers in the park on Oct. 3, 1933, when a small brush fire broke out around 2 p.m.

Accounts differ on whether workers were ordered by their foremen to head down into Mineral Wells Canyon to fight the fire or whether they were simply asked to help put out the flames.

Either way, into the canyon they went, with only shovels, their hands and the earth at their feet to work with.

Few, if any, of them would've had any experience fighting fires. But there were thousands of workers pitted against a small blaze.

"It was just a lark to us," the Los Angeles Times quoted one survivor saying in its Oct. 4, 1933, edition. "It didn't look dangerous then. We laughed about it and started down, to bat the fire out in a hurry."

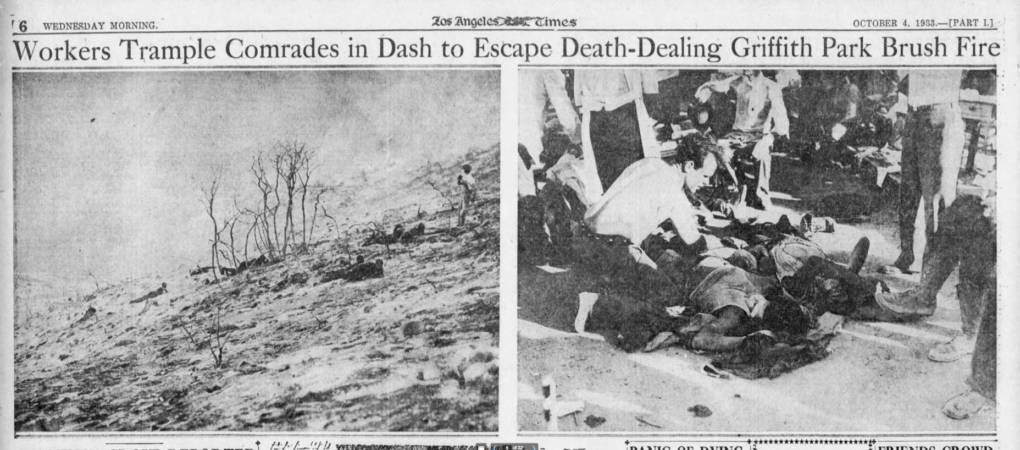

But around 3 p.m., the winds shifted. The small, harmless-looking brush fire became an inferno. As workers in the canyon tried to flee, they were met by additional workers pouring into the canyon, unaware of the fire's sudden change.

The volunteer firefighters tried to outrun the flames — either by running up out of the canyon or horizontally toward a main road.

'With Death Cries in Their Throats'

"Upward, upward, with death crackling and licking at their heels, struggled the workmen," wrote the Times the morning after. "Sent into the hills for rehabilitation, ordered into a fire trap for preservation of the hills — scrambling out of it with death cries dry in their throats."

The Los Angeles Fire Department arrived around 2:30 p.m. but was unprepared to deal with the mass of untrained firefighters battling the blaze. By evening, the professionals controlled the fire. But it had taken a shocking toll.

In the fire's aftermath, reports varied on how many men had died. The Times' morning-after headline proclaimed that 33 had perished, with a final death toll of 50 possible. The county coroner initially placed the number of dead between 70 and 80.

Confusion at the scene and the unreliability of the records showing who had been working that day contributed to the uncertainty over the death toll. The district attorney's office eventually placed the official tally at 29, but victims' groups argued that more than 50 had actually perished.

Initial reports cited a cigarette butt tossed away by a worker as the cause of the fire. Some tried to pin the blame on communists. But no one was ever identified as having started the blaze, and no arrests were made.

For a more detailed account of the fire and its aftermath, check out this three-part series of articles that originally appeared in the Glendale News-Press on Oct. 1, 2 and 4, 1993, which informed much of this report.

This post has been updated.