“We had to go all the way to Hayward to find a shelter that would take us, and I work in Oakland, my daughter goes to school in Oakland,” she said. “That was not sustainable for our lives.”

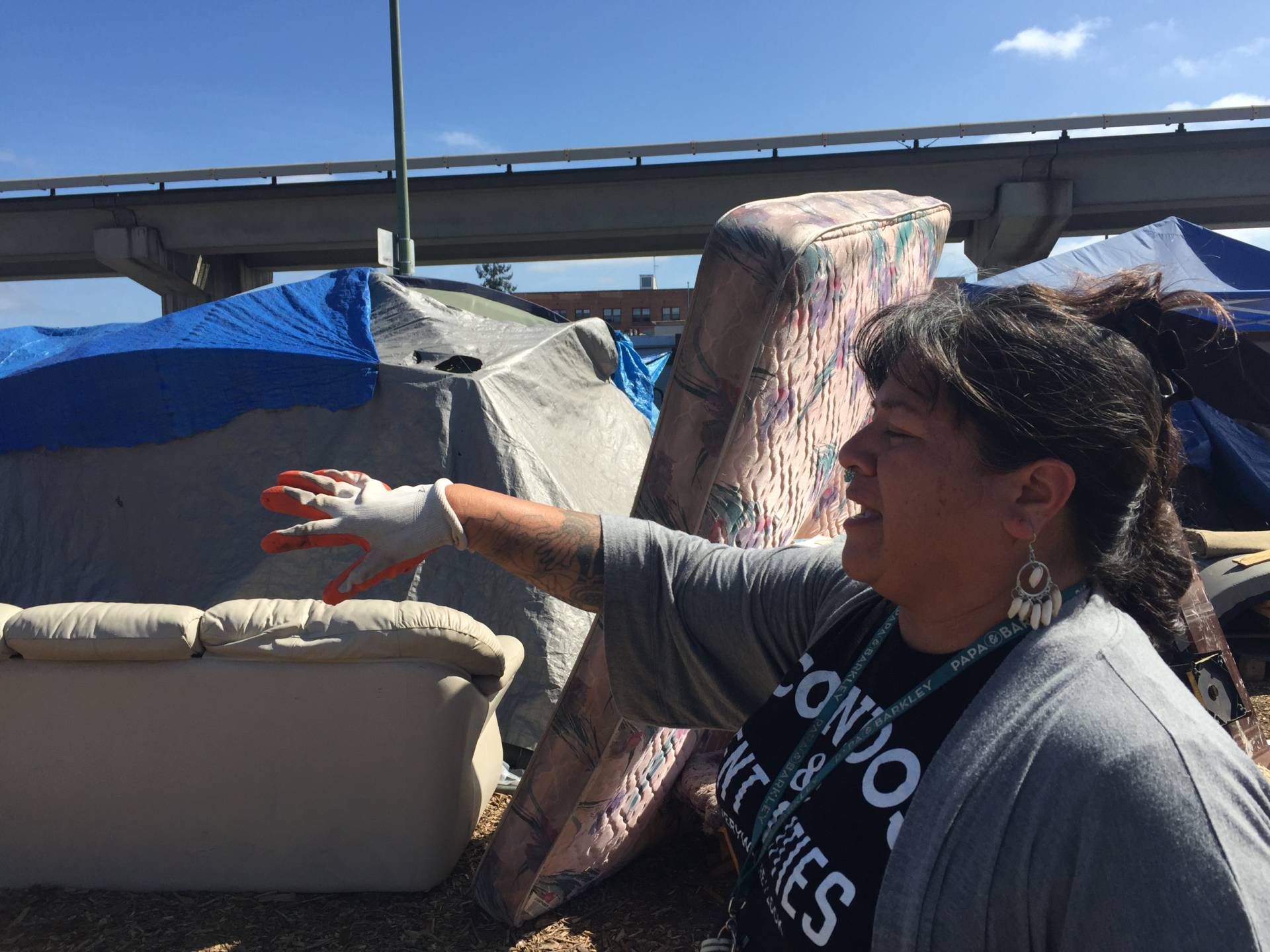

Women living on the streets face heightened risks and vulnerabilities, said Bee, who has squatted in abandoned houses and lived in a parked camper since losing her Oakland apartment last year.

“Every night men would find out that we’d be in a camper by ourselves, and they’d try to break into the camper,” she said. “Being at this village, we’ve not been broken into. No one’s trying to rape us.”

In court, the homeless group pointed to another federal case decided earlier this year — Martin v. Boise — in which the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled it unconstitutional for cities to prosecute the homeless for sleeping outside when not enough shelter space had been provided. Doing so, the court ruled, is a violation of the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.

“As long as there is no option of sleeping indoors, the government cannot criminalize indigent, homeless people for sleeping outdoors, on public property, on the false premise they had a choice in the matter,” Judge Marsha Berzon wrote for the majority.

But in court this week in Oakland, Deputy City Attorney Jamilah Jefferson told the judge that the city now has enough shelter beds for residents, and so would not be violating their rights in evicting them. Moving them to a shelter is legal, she argued, because it does not criminalize the residents.

In his ruling, Gilliam agreed with the city, writing that the Martin case “does not establish a constitutional right to occupy public property indefinitely at the Plaintiff’s option.”

But Joshua Piovia-Scott, an attorney representing the homeless group, countered that there is a notable gap between stated policy and actual implementation.

“What happens in reality on the street is very different than what the city of Oakland says in its policies,” he said.

“We submitted dozens of sworn declarations from people who are unhoused, who have been subject to arrest, harassment, citation, have had their belongings and their personal property destroyed, when this same type of notice to vacate has been served on them.”

The homeless group also argues that the shelter beds the city is offering don’t provide any kind of a realistic solution. Occupancy time limits, and rules against staying with minors or pets, they say, are some of the restrictions that make the shelters an unrealistic option for many homeless people.

Gilliam, however, told the courtroom that his job was not to judge the city’s policies, but rather to rule on their legality. In his ruling, he said the city must find shelter beds for all 13 residents currently located at the site in order to proceed with a legal eviction.

And, as Oakland pointed out in its case, there is no constitutional right to shelter.

The city must give residents 72 hours to remove their belongings from the encampment before being evicted.